Track and Field

The Black Track and Field Athletes from the past have made enormous contributions to the sport. Those track and field athletes had to face immense challenges and pressure to compete. Many thanks to the trailblazers who triumphed over oppression, racism and sexism that change the sport for the better. Their talent, courage, and determination paved the way for Black representation in sport.

The track and field athletes today owe so much to the pioneers of yesterday. From the first African American to win an Olympic gold medal, John Baxter Taylor, and the first the Black woman to win an Olympic gold medal, Audrey Patterson – the Black male and female track and field athletes are milestone makers, major achievers, and record setters that have revolutionize the sport.

We all know the exploits of Jesse Owens, and Wilma Rudolph, on the track. However these men and women weren’t just athletes, but were civil right advocates. When Rudolph returned to her hometown of Clarksville, Tennessee after her Olympic success, she found out that a parade and banquet would be held in her honor. She refused to attend when she learned the events would be racially segregated. Because of her protest, the celebrations became the first integrated events in her town.

Another was sprinter Wyomia Tyus, who wore Black running shorts in the 1968 Olympics, instead of team-issued white ones, to support the Olympic Project for Human Rights – an organization formed to protest racial segregation and racism in sports. Lee Evans wore a Black beret during the same Olympics for the same support. And as for John Carlos and Tommie Smith, their protest is legendary.

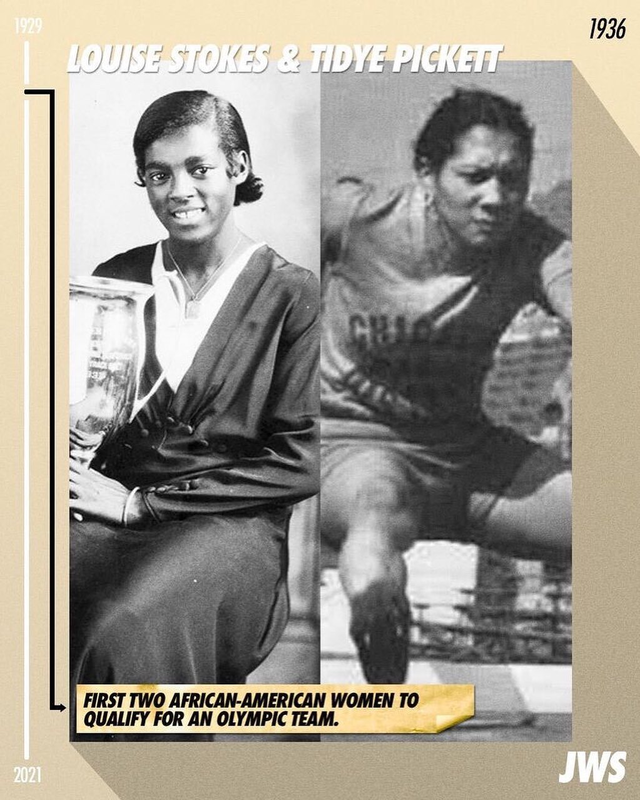

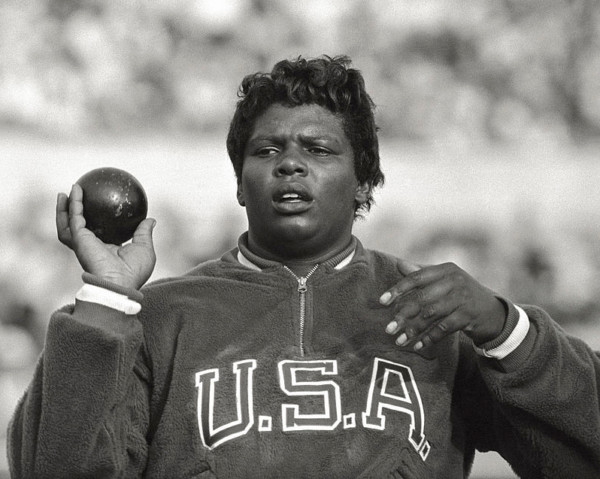

What about the Tennessee State Tigerbelles coached by Ed Temple, or Louise Stokes and Tidye Pickett, the first two Black females to qualify for the Olympics? And there is Earlene Brown who would become the first American woman to earn an Olympic medal in the shot put. Their stories and athletic achievements should be recognized and is every bit as important as the most famous ones.

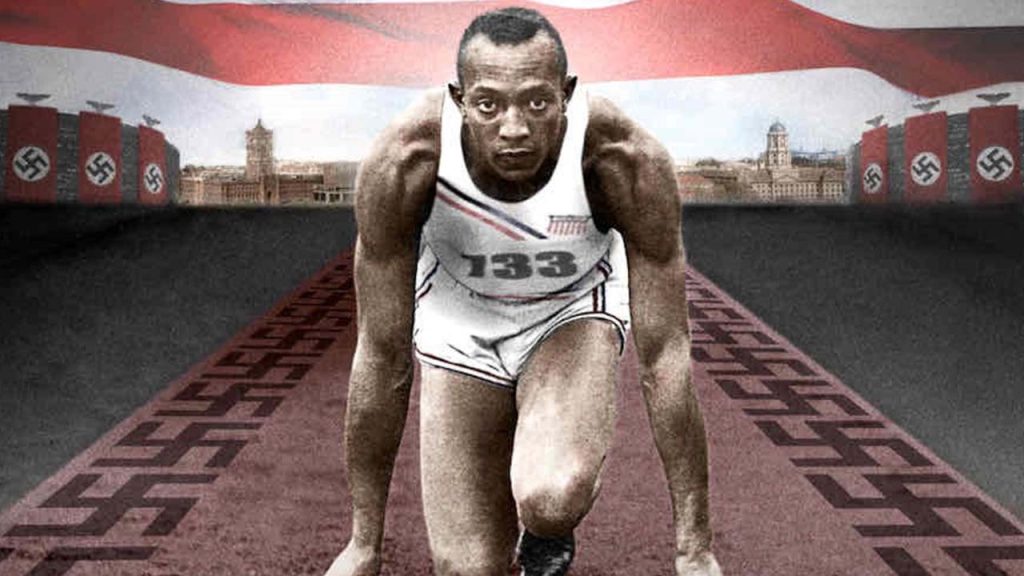

Jesse Owens

He was the first American to win four track and field medals in one Olympics, doing it as a Black man in 1936, made it all the more sweeter. James Cleveland Owens was the youngest of ten children was born on a tenant farm in Oakville, Alabama, March September 12th 1913. Jesse migrated with his family to Cleveland, OH, for better opportunities, as part of the Great Migration in 1922. When his new teacher asked his name, he said “J.C.”, but because of his strong Southern accent, she thought he said “Jesse”. The name took, and he was known as Jesse Owens for the rest of his life.

Owens's athletic talent was first noted at Fairmount Junior High School by his track coach. Jesse set a new junior high school record when he ran the 100-yard dash in 11 seconds flat. While at Fairmount, he also set records in the high jump and the long jump. Wishing to aid his struggling family, the practical Owens enrolled at East Technical High School in 1930, believing that a vocational education would guarantee future employment. As a high school senior in 1933 Jesse Owens won the 100-yard dash, the 200-yard dash, and the broad jump in the National Interscholastic Championships.

While as a student of East Technical High School in Cleveland, Owens first came to national attention. He equaled the world record of 9.4 seconds in the 100-yard dash and long-jumped 24 feet 9 1⁄2 inches at the 1933 National High School Championship. Owens was such a complete athlete, a coach said he seemed to float over the ground when he ran. He won the state championship three consecutive years. Owens’ sensational high school track career resulted in him being recruited by dozens of colleges.

Owens’s greatest achievement came in a span of 45 minutes on May 25, 1935, during Big Ten Championships, when he tied one world record and set 3 world records on the same day. Jesse entered the Big Ten Championships in 1935 with a sore back after falling down a flight of stairs. He set set world records in the long jump, 220-yard dash and 220-yard hurdles (22.6 seconds, becoming the first to break 23 seconds). Jesse recorded an official time of 9.4 seconds in the 100-yard dash, again tying the world record.

His long-jump record of 26 feet, 8 1/4 inches stood for 25 years. It remains a feat that has never been equaled. Some have called this incredible showing “the greatest single day performance in athletic history.” His dominance at the Big Ten games was par for the course for Owens that year. That year saw him win four events at the NCAA Championships, two events at the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) Championships, and three others at the Olympic Trials. In all, Owens competed in 42 events that year, winning them all earning him the title "The Buckeye Bullet".

Owens was a star track performer in college, but he also faced major challenges. His school did not offer scholarships for track and field, as the sport was not as well respected back then, so Owens had to work a series of jobs throughout college to pay for his tuition. In addition, the University did not allow Owens to live on campus because of his race. Owens, like many Black Americans during this time period, was subject to racist treatment and was often discriminated against.

Jesse Owens greatest fame, however, came a year later, in a politically charged environment. Owens traveled to Berlin to take part in the 1936 Olympics. Owens was easily the most dominant athlete to compete. For Adolf Hitler and the Nazis, the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games were expected to be a German showcase and a statement for Aryan supremacy. The 1936 Summer Olympics were the first to be broadcast on television and took place in Berlin, Germany, during a turbulent time. International tensions were high.

Europe was on the brink of World War II, which officially broke out three years after the Summer Olympics. People were terrified. But the games and the excitement surrounding them continued in spite of the impending war. Hitler lambasted America for including Black athletes on its Olympic roster. But it was the African American participants who helped cement America’s success at the Olympic Games. The reception Owens received in Berlin was cold. Hitler criticized the United States for including athletes of color and Jewish athletes on the roster.

In all, the United States won 11 gold medals, six of them by Black athletes. Owens’s performance at the 1936 Berlin Olympics has become legend. On August 3, 1936 Jesse Owens won gold for the 100m sprint, defeating Ralph Metcalfe. The following day, he finished first in the long jump, where he set an Olympic record of 26 feet, 5 1/4 inches. On August 5th, Owens continued his win streak by taking the 200m sprint, setting an Olympic record of 20.7 seconds. After he was added to the 4 x 100 m relay team, he won his fourth gold medal on August 9th.

Winning 4 gold medals in a single Olympic year was unequaled until Carl Lewis won gold medals in the same events at the 1984 Summer Olympics. Despite the politically charged atmosphere of the Berlin Games, Owens was adored by the German public. But when the four-time Olympic gold medalist returned home, he could not even ride in the front of a bus. After a New York City ticker-tape parade of Fifth Avenue in his honor, Owens had to ride the freight elevator at the Waldorf-Astoria to reach the reception honoring him.

Jesse Owens struggled financially after the Olympics and had a hard time even completing his college degree. Despite the four gold medals Jesse Owens brought home for his country, he was soon relegated to the second class citizen status Black Americans found themselves in during the 1930's and 1940's. Interested in using the status of his name, Owens took up a wide range of jobs over the years. He raced local amateur sprinters for money. He opened a chain of dry cleaning stores, but the business failed.

In 1946 became the owner of the Portland Rosebuds, a baseball team playing in the West Coast Baseball Association (WCBA), a newly created Negro baseball league. After two months, however, the WCBA folded. He traveled around the globe as a goodwill ambassador for the U.S. government, and he booked speaking engagements with various corporate clients. Although Owens’ world records have since been broken, his athletic legacy continues. He was part of the first class of athletes to be inducted into the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame in 1983. In 1990, President George H.W. Bush posthumously awarded him the Congressional Medal of Honor.

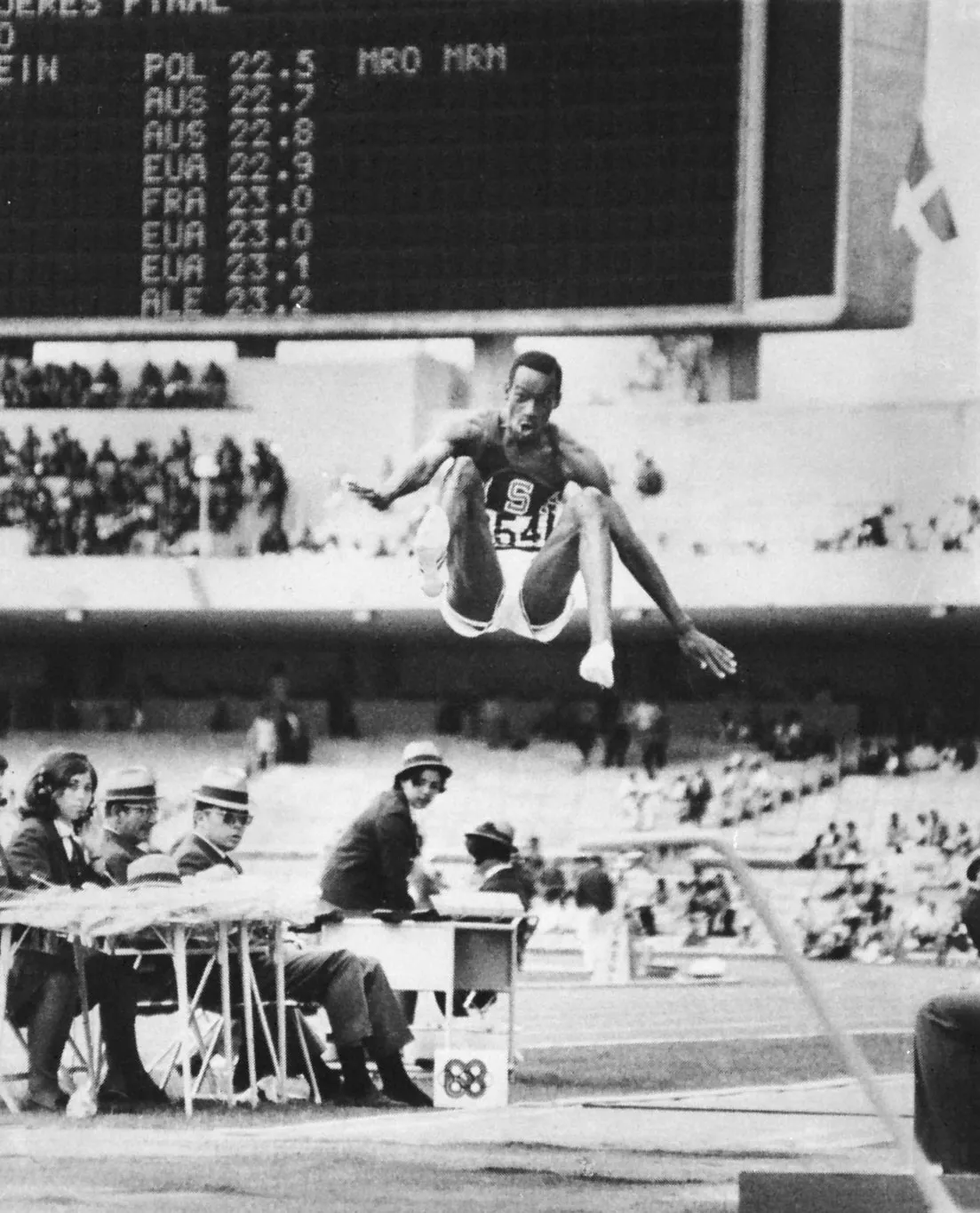

Ralph Boston

He was the first person to long jump more than twenty-seven feet. Track star and medalist in the 1960, 1964, and 1968 Olympic games, Ralph Boston was born in Laurel, Mississippi on May 9, 1939. Boston was born the youngest of ten children. As a Black child growing up in the Jim Crow South, Boston knew hard work at a young age. He rose early with his father to work in the fields before attending class at Oak Park Vocational School.

One of his earliest memories is of riding a mule-pulled wagon across the railroad tracks with his father, from his all-Black neighborhood of Queensburg and into the white community. It was then that he first noticed a stark contrast: the streets, the housing, the parks, and other facilities in White neighborhoods were far superior to those in Queensburg. When he was not working or studying, Boston enjoyed swimming in a creek outside Laurel, and after the city opened the Blacks-only Oak Park Pool, he became a lifeguard at the facility.

Ralph Boston was a track and field star in both his junior and senior high school years. He was virtually a one-man track team, winning or placing in hurdling, throwing, sprinting, and jumping events. His Oak Park team continued its run of high school track championships. He set a national high school record in the 180-yard hurdles and excelled as the school’s starting quarterback in football and their star forward in basketball. Boston was an elite quarterback and led the Oak Park Dragons to the Negro state football championship.

As a senior, he received scholarship offers to play football, but followed the advice of his mother, Eulalia, and his track coach, Joseph Frye, to pursue a career in track and field. In later interviews, he gave credit for his successes to the dedicated teachers at Oak Park, who also provided him with a solid academic foundation despite the lack of access to adequate educational resources and facilities. Upon graduating from Oak Park in 1957, Boston was offered a track scholarship at Tennessee State University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Boston enrolled at Tennessee State University, where he studied biochemistry. He started competing in high and low hurdles, high jump, and triple jump. His signature event, however, was the long jump. He won the 1960 Collegiate long jump title. In August, he burst onto the national scene at a conditioning meet in Los Angeles that served as a final tune up before the 1960 Rome Olympics. At the MT SAC Relays, an athletics event at San Antonio College in California, he jumped 26ft 11in, three inches longer than Jesse Owens had managed in 1935.

The U.S. track team broke four world records in that event, but it was Boston’s long jump — of 26 feet, 11 inches — that made the biggest headlines. That year he was selected as a World Athlete of the Year and as the North American Athlete of the Year. Later that year, in 1960, he travelled to Rome for the Olympics. Boston triumphed in Rome. Boston then broke the Olympic record (26 foot 7½ inches) to win the gold medal in Rome. Boston had just turned 21 and he had outleaped a legend.

The legend was humble. “I’m happy to see the record broken, and I’m just thankful that it stood up this long,” said 4-time gold medalist Owens to an AP reporter. The following year at the Modesto Relays in California, Boston extended his world record to a history-making 27ft 1/4in. Ralph Boston, was the first man to jump more than 27 feet. Ralph Boston became a world-recognized track star when he jumped further than any other recorded person in 1961. His personal best was a leap of 27 feet 5 inches at Modesto in 1965.

He entered into a rivalry with the Soviet jumper Igor Ter-Ovanesyen and broke the record four more times over the next few years – giving him six record marks, more than any other long jumper. He was favored to repeat his Olympic victory at the 1964 Games in Tokyo. A steady rain and strong winds that affected his jumps led to an unexpected upset. Lynn Davies of Britain, a relative unknown, stood at the end of the runway and waited for the wind to die down for his final jump. When the wind momentarily calmed, he jumped to first place with a distance of 26 feet 5½ inches.

Lynn Davies, took the gold with a jump that was actually shorter than Jesse Owens’s world record 33 years previously. Until then, Ter-Ovanesyan, who had never beaten Boston in an outdoor meet, was ahead going into that fifth and final jump. Boston overtook the Soviet, Ter-Ovanesyen to the silver medal, but could not overtake the new Olympic champion, Lyn Davies. He was the AAU long jump champion from 1961 to 1966. In 1967, when Bob Beamon was suspended for refusing to compete against Brigham Young University, who was accused of having racist policies, Boston stepped in to coach him unofficially.

At the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, Boston was the World and Olympic record holder in the long jump, but the three-time Olympian knew he was approaching the end of his career. He knew that Beamon had a better chance than he did to re-take the long jump Olympic championship back. At twenty-nine, he won a bronze, finishing behind Bob Beamon at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. Boston retired internationally after the 1968 Olympics, while continuing to compete at home.

He was the field event reporter for the CBS Sports Spectacular coverage of domestic track and field events. He went on to work as an administrator and served as coordinator of minority affairs and assistant dean of students at the University of Tennessee from 1968 to 1975. He was selected to the United States Track and Field Hall of Fame in 1975, and in 1976 was the first Black athlete inducted into the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame. In 1985 Ralph Boston was inducted into the Olympic Hall of Fame.

He became a corporate executive, eventually joining ServiceMaster Services, a cleaning company, in Stone Mountain, Georgia, as president and CEO. Boston was also known as a generous mentor and coach to fellow athletes. Beamon credited Boston for making Beamon’s record-breaking jump in Mexico City possible. “What people don’t know is that I wouldn’t have done that if it hadn’t been for Ralph Boston,” he told the news website Mississippi Today in 2021. “I fouled on my first two attempts and was about to get disqualified, and then Ralph told me I needed to adjust my footwork leading to my takeoff. I figured I had better listen to the master, and I did.”

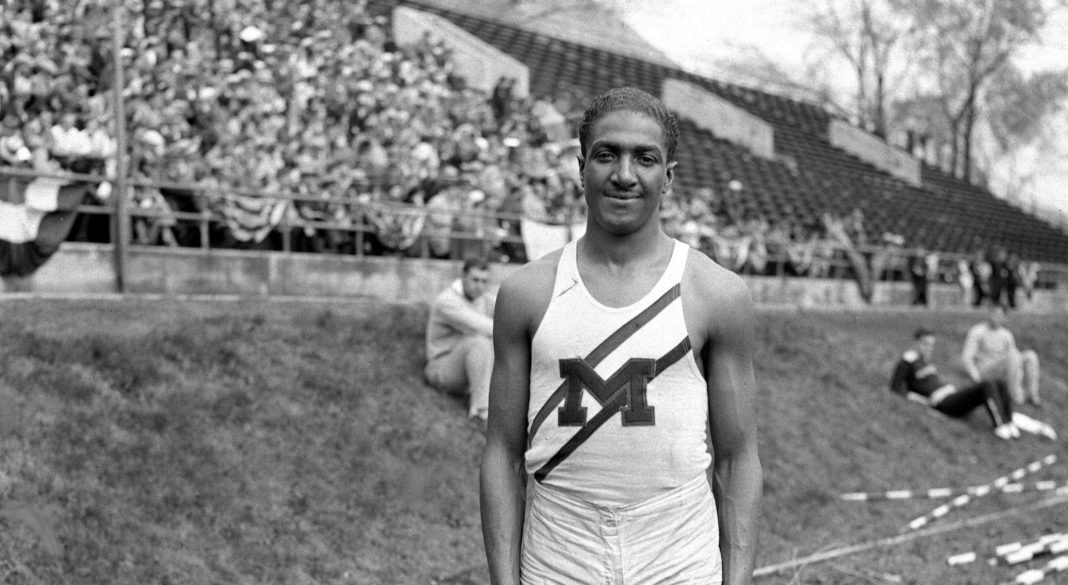

Ralph Metcalfe

He competed in both the 1932 and 1936 Olympic Games, ending up with one gold medal, two silvers and a bronze. Ralph Metcalfe was born in Atlanta, Georgia and raised in Chicago, Illinois. His family moved north to Chicago when he was seven, during the early years of what became known as the Great Migration. Metcalfe excelled as a sprinter at Tilden Tech High School on the city’s south side, where his coach instilled in him a work ethic that encapsulated well the Black experience.

He earned a scholarship to Marquette University in Milwaukee in 1930 when he became the school's first Black student-athlete. During his sophomore year at Marquette, Metcalfe equaled the world of record of 10.3 seconds in the 100-meter dash, as well as the 200-meter world record of 20.6 seconds. He won the first of three NCAA championships from 1932 to 1934, in both the 100- and 200-meter dashes. He achieved the same double victories in the national AAU meet during those years and wound up with five straight national titles in the 200 and 220yd.

Overall, counting indoor competition, Metcalfe won 11 AAU sprint titles. In the early 1930s, Ralph Metcalfe was the prime U.S. sprinter, winning most of the national titles and tying the world records in the 100 and 200 meters. He equalled the world record in Budapest the following year, and again at competitions in the Japanese cities of Nishinomiya and Dairen in 1934. He continued to thrive on the track team and by the Spring of 1932, he had broken several world records.

On June 10, Metcalfe broke three world records and tied a fourth in the span of one hour during a track meet. He quickly gained the attention of several U.S. newspapers by qualifying for the 1932 U.S. Olympic team. The 1932 Summer Olympics were held in Los Angeles, California. Metcalfe was a favorite to win the sprint competitions along with fellow U.S. Olympians Eddie Tolan of the University of Michigan and George Simpson of Ohio State University. He won both the 100m and 200m runs at the Olympic Trials, but failed to maintain his dominance at the Los Angeles Olympics.

He raced to virtual tie with Eddie Tolan in the 100 meters. After an exhaustive review officials awarded the gold medal to Tolan and silver medal to Metcalfe. Their record setting time of 10.37-seconds remained unbroken for 32 years. In the 200m, he again was unlucky, since it appeared that he had been placed 3-4 feet behind his fellow finalists at the starting line. He was unable to make up the distance, finishing third to Tolan and fellow American George Simpson to take the bronze.

After the Olympics, Metcalfe turned more of his attention towards his education. He was elected class president and was inducted into the university’s honor society. Metcalfe was an outstanding student and campus leader. In 1933, he was inducted into Alpha Sigma Nu, which is the elite Jesuit academic honor society on campus. At the Amateur Athletic Union national championship at the former Marquette Stadium in 1934, Metcalfe bested Olympic great Jesse Owens in the 100-meter dash. Owens and Metcalfe would go on to be rivals and teammates.

In 1934, Metcalfe graduated with a bachelor’s degree in philosophy and was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity Incorporated. He also mentored a few college athletes, including Ohio State University’s track star, Jesse Owens. In 1934, Metcalfe tied the world 100m record of 10.3 three times, as well as the 200-meter world record of 20.6 seconds during a tour of Europe and Asia. Metcalfe was undefeated in track-and-field competitions between the fall of 1932 and spring of 1936.

During that time, he was nicknamed the “World’s Fastest Human” after breaking seven world records and tying two more sprint events from the 40-yard sprint to the 200-meter sprint. This earned him a return engagement to the Olympic Games in 1936, this time staged in Berlin, where he found himself at a historic convergence of politics, race and sport - this time as a teammate of Jesse Owens, and as the track team's elder statesman. He finally won an Olympic gold medal in the 4x100m relay at the 1936 Berlin Games after taking second, and the silver to Jesse Owens in the 100m.

While long-time rivals - Metcalfe beat Owens on several occasions in the early 1930s - he and Owens also became life-long friends, with the legend crediting Metcalfe with the victory in the relay. While his starts were comparatively weak, Metcalfe had an extremely long stride and was noted for the strength of his finishes. At least eight times he equaled the world record of 10.3 for the 100 meters six times, but only three of those clockings reached the record books.

After his retirement following the 1936 Games, Metcalfe attended the University of Southern California. After his college career, he joined the armed forces and served in World War II. During World War II he joined the armed forces and fought to end Jim Crow segregation in America and end fascism abroad, better known as the Double-V movement. In June 1943, Metcalfe served as associate director of the Louisiana USO Maneuver Service. In this role, he helped organize a track meet at Fort Huachuca in collaboration with the all-Black units of the 93rd Infantry Division.

He eventually rose in rank to first lieutenant and earning the Legion of Merit for his physical education training program. Metcalfe later taught political science and coached track at Xavier College in Louisiana before becoming a successful businessman in Chicago. He began a political career in 1949, becoming an alderman for the city of Chicago. In 1952, became a Democratic committeeman for the Third Ward; Metcalfe was elected alderman in 1955 and was reelected three times.

In 1970, Metcalfe Metcalfe was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, succeeding his mentor, the late William Dawson. Metcalfe began his career as a Daley loyalist but later broke with the mayor, becoming a strong and independent voice for his mostly African American constituency who felt ignored by the workings of the Daley machine. Metcalfe was elected to four terms in Congress. Metcalfe co-founded the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), was inducted into the United States Track and Field Hall of Fame (1975), and was named a member of the President’s Commission on Olympic Sports.

Evelyn Ashford

She is recognized as one of track and field history's most accomplished sprinters. Evelyn Ashford is the first woman in U.S. track history to win four Olympic gold medals—one in the 100-meter sprint and three as part of 4 × 100-meter relay teams. Born in Shreveport, LA. in April 1957, Evelyn Ashford was part of a military family. Being part of a military family, she moved quite a few times growing up. She went to four different schools in four different cities before Evelyn's family settled in Sacramento, CA area in 1973. It was here that Evelyn attended Roseville High School.

At the local high school, Ashford joined the boys’ track team because the school did not have one for girls. She won most of her races there. By the time she was 15 years old, Evelyn Ashford had to her credit 2 state and 1 national track record and had led her track team at Clements High School to back-to-back State Championships in 1971-72. She was the star of the Tigers track team and set numerous records during her high school years. Her talent caught the attention of the track coach at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA).

She earned a scholarship to UCLA one of the school's first women’s athletic scholarships. Former Olympian Pat Connolly coached Ashford at UCLA. At the 1976 Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) national championships, Ashford finished second in the 100 meters. She was so impressive that after her freshmen year she earned a spot on the United States Olympic team at just 19 years old. As a 19-year-old, she finished a surprise 5th at the 1976 Summer Games in Montreal in the 100 meters.

After the 1976 Olympics she returned to collegiate athletics, winning several individual and team relay events. Before long, Evelyn emerged as one of the world's greatest sprinters. She helped UCLA win the 1977 AIAW Outdoor competition earning All-American honors in 1977 and 1978. In the late 1970s she decided to drop out of college to concentrate on training. She had recently set a United States record of 21.83 seconds in the 200 meters and had beaten world-record holder Marlies Göhr of East Germany in the 100 meters at the World Cup.

Ater beating the World Record holders Marlies Gohr and Marita Koch in the 1979 World Cup, Evelyn Ashford became one of the potential gold medalists for the 1980 Summer Olympics. She was ranked No. 1 in the world by Track & Field News over 100 meters. She was the favorite to win both the 100 meters and 200 meters, but the U.S. boycott of the the 1980 Moscow Olympics kept her at home. Evelyn would have to wait four years before she would get the chance to attempt to capture an Olympic medal.

Ashford contemplated quitting track. Shortly after the boycott, she tore a hamstring muscle and took off the rest of the year. Evelyn’s work ethic and determination would not be put on hold as she prepared for the 1984 Games. She went on to win another two world championships in 1981, when she was named Woman Athlete of the Year. On July 3, 1983, she was in prime form setting the world record in the 100 meters in 10.79 seconds at the National Sports Festival in Colorado Springs, Colorado. In doing so, she became the first woman in the world to ever run under 11 seconds.

It was now time for the 1984 Olympic Games on her home turf in Los Angeles. It was Evelyn’s time to shine and she didn’t disappoint. Ashford first chance to win a medal was in the 200 meters, however she had to withdraw from the 200-meter heats due to an injury.. Evelyn won the Gold Medal in the 100m, setting a new Olympic record. She was also a member of the Gold-medal-winning 4 × 100-meter relay team that included Alice Brown, Jeanette Bolden, and Chandra Cheesborough. Later in 1984, Ashford set a world record in the 100 meters with a time of 10.76. The record stood until 1988.

In 1985, while still preparing for her next Olympics, Evelyn and her husband, Ray Washington, welcomed a baby girl, Raina. At the 1988 Seoul Summer Olympics, she was beaten in the 100 meter by Florence Griffith Joyner, who had broken her World Record earlier at the Olympic Trials. Ashford won a Silver medal in the 100 meters and a Gold medal in the 4 × 100-meter relays. But her proudest moment was being selected as the United States flag bearer during the Opening Ceremonies in the Seoul, South Korea games.

By the time the next Games would come around Evelyn would be 35 years old but that wasn’t going to stop her. History was made at the 1992 Barcelona games, as she became the oldest woman to ever win an Olympic Gold Medal in Track and Field! Evelyn earned her 4th and final Olympic gold medal as a part of the 4x100 team at the 1992 Barcelona Games. Ashford became the first Black woman to win 4 Olympic Gold medals. Evelyn’s Olympic career spanned over five Olympiads and she competed in four Olympic Games winning five medals in all - four Gold Medals and one Silvers.

Evelyn Ashford is without question one of the greatest athletes in the history of Track and Field. She is remembered for being one of the all-time greats in any sport from our area. She is a five-time Olympic medalist, four-time gold medalist and the first woman to run the 100-meter dash in under 11 seconds. Evelyn has been honored numerous times over the years for her contributions to her sport including induction into the National Track & Field Hall of Fame, UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame and the U.S. Olympic Hall of Fame.

Ralph Boston

He was the first person to long jump more than twenty-seven feet. Track star and medalist in the 1960, 1964, and 1968 Olympic games, Ralph Boston was born in Laurel, Mississippi on May 9, 1939. Boston was born the youngest of ten children. As a Black child growing up in the Jim Crow South, Boston knew hard work at a young age. He rose early with his father to work in the fields before attending class at Oak Park Vocational School.

One of his earliest memories is of riding a mule-pulled wagon across the railroad tracks with his father, from his all-Black neighborhood of Queensburg and into the white community. It was then that he first noticed a stark contrast: the streets, the housing, the parks, and other facilities in White neighborhoods were far superior to those in Queensburg. When he was not working or studying, Boston enjoyed swimming in a creek outside Laurel, and after the city opened the Blacks-only Oak Park Pool, he became a lifeguard at the facility.

Ralph Boston was a track and field star in both his junior and senior high school years. He was virtually a one-man track team, winning or placing in hurdling, throwing, sprinting, and jumping events. His Oak Park team continued its run of high school track championships. He set a national high school record in the 180-yard hurdles and excelled as the school’s starting quarterback in football and their star forward in basketball. Boston was an elite quarterback and led the Oak Park Dragons to the Negro state football championship.

As a senior, he received scholarship offers to play football, but followed the advice of his mother, Eulalia, and his track coach, Joseph Frye, to pursue a career in track and field. In later interviews, he gave credit for his successes to the dedicated teachers at Oak Park, who also provided him with a solid academic foundation despite the lack of access to adequate educational resources and facilities. Upon graduating from Oak Park in 1957, Boston was offered a track scholarship at Tennessee State University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Boston enrolled at Tennessee State University, where he studied biochemistry. He started competing in high and low hurdles, high jump, and triple jump. His signature event, however, was the long jump. He won the 1960 Collegiate long jump title. In August, he burst onto the national scene at a conditioning meet in Los Angeles that served as a final tune up before the 1960 Rome Olympics. At the MT SAC Relays, an athletics event at San Antonio College in California, he jumped 26ft 11in, three inches longer than Jesse Owens had managed in 1935.

The U.S. track team broke four world records in that event, but it was Boston’s long jump — of 26 feet, 11 inches — that made the biggest headlines. That year he was selected as a World Athlete of the Year and as the North American Athlete of the Year. Later that year, in 1960, he travelled to Rome for the Olympics. Boston triumphed in Rome. Boston then broke the Olympic record (26 foot 7½ inches) to win the gold medal in Rome. Boston had just turned 21 and he had outleaped a legend.

The legend was humble. “I’m happy to see the record broken, and I’m just thankful that it stood up this long,” said 4-time gold medalist Owens to an AP reporter. The following year at the Modesto Relays in California, Boston extended his world record to a history-making 27ft 1/4in. Ralph Boston, was the first man to jump more than 27 feet. Ralph Boston became a world-recognized track star when he jumped further than any other recorded person in 1961. His personal best was a leap of 27 feet 5 inches at Modesto in 1965.

He entered into a rivalry with the Soviet jumper Igor Ter-Ovanesyen and broke the record four more times over the next few years – giving him six record marks, more than any other long jumper. He was favored to repeat his Olympic victory at the 1964 Games in Tokyo. A steady rain and strong winds that affected his jumps led to an unexpected upset. Lynn Davies of Britain, a relative unknown, stood at the end of the runway and waited for the wind to die down for his final jump. When the wind momentarily calmed, he jumped to first place with a distance of 26 feet 5½ inches.

Lynn Davies, took the gold with a jump that was actually shorter than Jesse Owens’s world record 33 years previously. Until then, Ter-Ovanesyan, who had never beaten Boston in an outdoor meet, was ahead going into that fifth and final jump. Boston overtook the Soviet, Ter-Ovanesyen to the silver medal, but could not overtake the new Olympic champion, Lyn Davies. He was the AAU long jump champion from 1961 to 1966. In 1967, when Bob Beamon was suspended for refusing to compete against Brigham Young University, who was accused of having racist policies, Boston stepped in to coach him unofficially.

At the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, Boston was the World and Olympic record holder in the long jump, but the three-time Olympian knew he was approaching the end of his career. He knew that Beamon had a better chance than he did to re-take the long jump Olympic championship back. At twenty-nine, he won a bronze, finishing behind Bob Beamon at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. Boston retired internationally after the 1968 Olympics, while continuing to compete at home.

He was the field event reporter for the CBS Sports Spectacular coverage of domestic track and field events. He went on to work as an administrator and served as coordinator of minority affairs and assistant dean of students at the University of Tennessee from 1968 to 1975. He was selected to the United States Track and Field Hall of Fame in 1975, and in 1976 was the first Black athlete inducted into the Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame. In 1985 Ralph Boston was inducted into the Olympic Hall of Fame.

He became a corporate executive, eventually joining ServiceMaster Services, a cleaning company, in Stone Mountain, Georgia, as president and CEO. Boston was also known as a generous mentor and coach to fellow athletes. Beamon credited Boston for making Beamon’s record-breaking jump in Mexico City possible. “What people don’t know is that I wouldn’t have done that if it hadn’t been for Ralph Boston,” he told the news website Mississippi Today in 2021. “I fouled on my first two attempts and was about to get disqualified, and then Ralph told me I needed to adjust my footwork leading to my takeoff. I figured I had better listen to the master, and I did.”

Alice Coachman

The first Black woman from any country to win an Olympic gold medal was Alice Coachman. Alice Coachman was born on November 9, 1923 in Albany, Georgia, she was the fifth of ten children born. Growing up in the segregated South, she overcame discrimination and unequal access to inspire generations of other Black athletes to reach for their athletic goals. As a child, Alice was a tomboy, but her father, influenced by society's reluctance to accept female athletes. , But at that time it wasn’t socially acceptable for women to be athletes.

Fearing for her safety as an African American in a segregated society, he initially discouraged her from sports. The family worked hard, and a young Coachman helped. Her daily routine included going to school and supplementing the family income by picking cotton, supplying corn to local mills, or picking plums and pecans to sell. Beyond these tasks, the young Coachman was also very athletic. It was her fifth-grade teacher at Monroe Street Elementary School, Cora Bailey, and her aunt, Carrie Spry, who encouraged her to continue running.

By seventh grade, she was one of the best athletes in Albany, boy or girl. Barred from training with White children or using White athletic facilities, young Coachman trained on her own. She ran barefoot on dusty roads to improve her stamina and used sticks and rope to practice the high jump. She also figured out ways to rig up a high jump bar so she could practice the sports she observed others doing. Coachman entered Madison High School in Albany in 1938 and joined the track team, soon attracting a great deal of local attention.

Within a year she caught the eye of the boys’ track coach, Harry E. Lash. He began working with her to develop what he saw as a special, natural talent. While competing for her high school track team in Albany, her ability was noted by a representative from the athletic department of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. In the rural south during the time when Jim Crow laws still reigned, Alice Coachman was not guaranteed an opportunity for an education. The school offered her a scholarship to come there.

At age 16, she received a scholarship to the prestigious Tuskegee Preparatory School. In 1939 she won her first Amateur Athletic Union Championship in the high jump, breaking both the collegiate and national high jump records. As a member of the track-and-field team, she won four national championships for sprinting and high jumping. High jump was her event, and from 1939 to 1948, Coachman won 10 straight championships in the high jump, as well as 25 indoor and outdoor 50- and 100-meter championships.

She was one of the best track-and-field competitors in the country, winning national titles in the 50m, 100m, and 400m relay. She also played on the Tuskegee basketball team, and they won three national titles while she was there. She was the only African American on each of the five All-American teams to which she was named. People started pushing Coachman to try out for the Olympics. The Olympics were out of reach. During Coachman's prime athletic years, the 1940 and 1944 Olympic Games were cancelled because of World War II.

Alice Coachman received a trade degree in dressmaking in 1946 from the Tuskegee Preparatory School and went on to enroll at Albany State University. In 1948, however, she finally had her chance at the 14th modern Olympics, which were held in London that year. Still wanting to go to the Olympics, Alice worked tirelessly and finally qualified for the 1948 Olympics at the age of 25, with a 5 feet 4 inch jump, breaking the previous record of 5 feet 3-1/4 inches set in 1932. Alice Coachman had achieved her dream by winning a spot on the US Olympic team!

She captured the gold in the high jump. Coachman set an Olympic record before 83,000 people in the high jump with a leap of 5 feet, 6-1/8 inches—a feat that stood for eight years. With this medal, Coachman became not only the first Black woman to win Olympic gold, but the only American woman to win a gold medal at the 1948 Olympic Games. King George VI of Great Britain put the medal around her neck. Upon returning to the United States, Coachman and several other black Olympians met with Pres. Harry Truman at the White House.

But like many of the Black soldiers returning from World War II, when Coachman returned to the United States, she was reminded of the current state of her own country. While the life at the Olympics had been fully integrated, Coachman returned home to a “hero’s welcome” in the segregated South. A parade was held in Albany, Georgia, where it culminated at the local theater, where there was a ceremony in her honor. She was the guest of honor at a party thrown by famed jazz musician William "Count" Basie.

In addition to meeting many famous people who also gave parties for her, she was given a parade in her honor, given a victory ride from Atlanta to Macon, and given a banquet by her sorority, Delta Sigma Theta. However, audience members and the people on stage all obeyed the segregation practices of the day. When she attended a celebration at the Albany Municipal Auditorium, she entered a stage divided by race—whites on one side, Blacks on the other. Coachman realized that nothing had changed despite her athletic success.

She never again competed in track events. After the 1948 Olympics, Alice Coachman retired from athletic competitions, but she remained in the public eye and was a role model. A dozen years later, she watched Wilma Rudolph, who recovered from infantile paralysis caused by polio to win three gold medals in Rome in 1960. She married N. F. Davis, had two children. Alice Coachman taught physical education, coached, and became involved in the Job Corps in Albany Georgia. She also taught at South Carolina State College, Albany State College, and Tuskegee High School.

In 1952, the Coca Cola Company offered her a contract to be a spokesman for the company, making her the first African-American female to benefit from a commercial endorsement deal. Later she established the Alice Coachman Track and Field Foundation to help support young athletes and provide assistance to retired Olympic athletes. She was one of 12 torchbearers for the 1996 Olympic games in Atlanta, GA. Alice was honored at the Olympic ceremony as one of the 100 greatest Olympians. She is a member of the USA Track and Field Hall of Fame and the United States Olympic Hall of Fame.

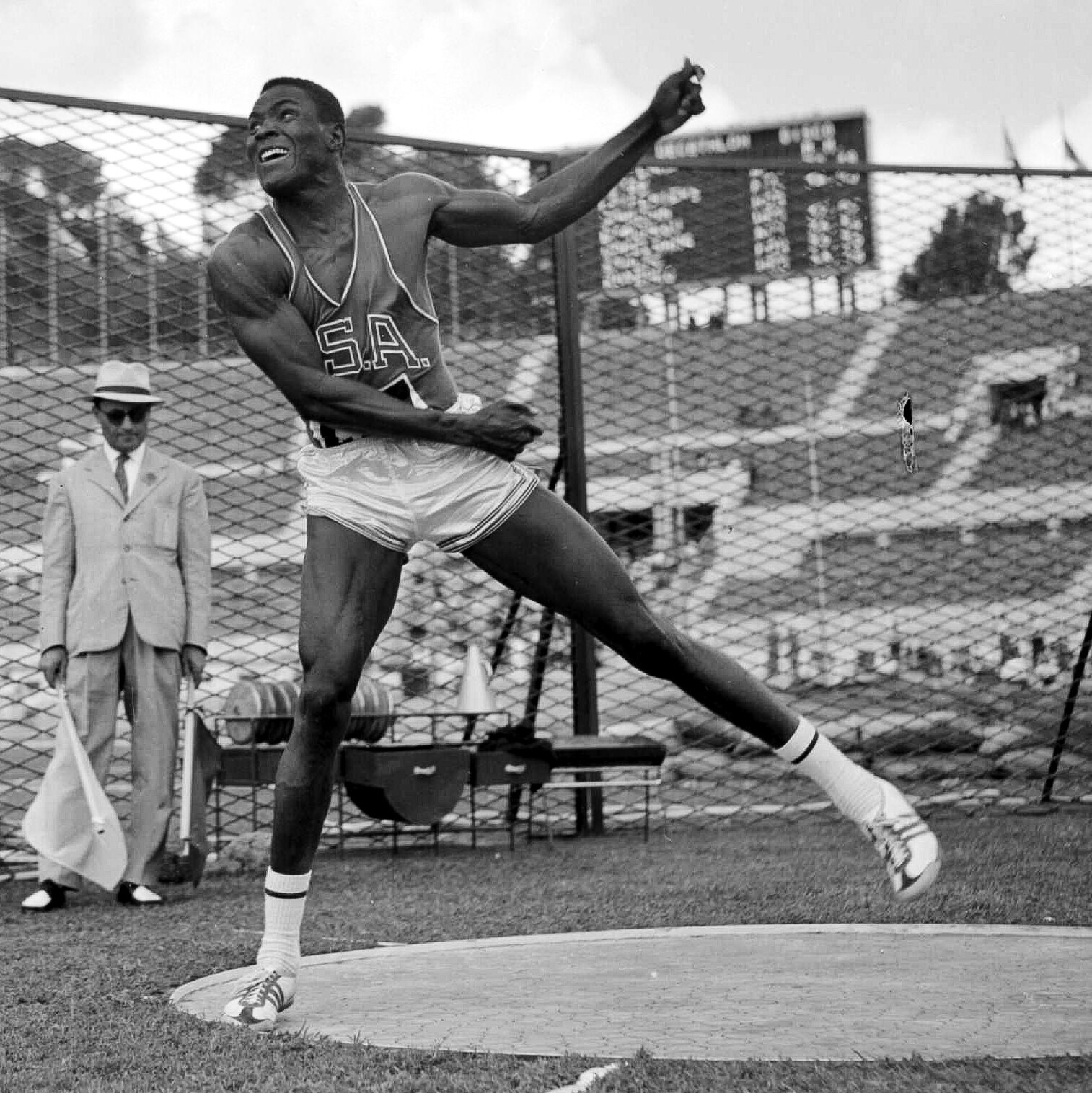

Rafer Johnson

At the 1960 Olympic Games he became the first African American athlete to carry the U.S. flag in the Olympic procession, and he captured the decathlon gold medal. Rafer Lewis Johnson was born on August 18, 1935, in Hillsboro, Texas. Rafer was one of six children. His brother, Jimmy Johnson, played defensive back for the San Francisco 49ers and is a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. In hopes of bettering their living conditions, the Johnson family moved to Kingsburg, in California's San Joaquin Valley, when Rafer was nine years old.

He attended Kingsburg High School where he was part of the football, basketball, baseball, and track teams. As a halfback, Rafer averaged more than nine yards every time he carried the football and led his team to three league championships. He was also an outstanding basketball player, averaging 17 points per game. Rafer was the center fielder in baseball, where he batted more than .400, including a .512 average in his junior year. He was also elected student body president.

The summer between his sophomore and junior years in high school, his coach drove Johnson 24 miles to Tulare and watched Bob Mathias compete in the 1952 U.S. Olympic decathlon trials. Johnson told his coach, "I could have beaten most of those guys." In the end track and field became his main sport. He won state championships in the 110-yard hurdles and the decathlon. Weeks later, Johnson competed in a high school invitational decathlon and won the event. He also won the 1953 and 1954 California state high school decathlon meets.

Rafer Johnson was offered a football scholarship but decided football was too risky for his track career. Fearing injury, he decided to quit playing football for good. Attending UCLA, Johnson was active in college pledging the Pi Lambda Phi fraternity, and being elected the class President in 1955. In 1954 as a freshman at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), his progress in the event was impressive. Johnson completed in his first decathlon in 1954 as a sophomore at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

He went to the Pan Am Games in Mexico City and won the decathlon title in 1955, scoring a total of 6,994 points. He won the AAU decathlon in 1956, 1958, and 1960. At UCLA, Johnson also played basketball under legendary coach John Wooden and was a starter for the Bruins on their 1958–59 team. Johnson qualified for both the decathlon and the long jump events for the 1956 Summer Olympics. He was hampered by an injury and forfeited his place in the long jump. The old football injuries that he feared had caught up with him.

Despite this handicap, he managed to take second place to win a silver medal in the decathlon at the 1956 Summer Olympics in Melbourne, Australia behind compatriot Milt Campbell. It would turn out to be his last defeat in the event. Johnson missed the 1957 and 1959 track seasons because of injuries. Between the 1956 and 1960 Olympics, Johnson, Russian Vassily Kuznetsov, and Taiwan's C.K Yang rewrote the decathlon record book.

In 1960, Johnson made history by becoming the first Black person to carry the flag for the United States at an opening ceremony of an Olympic Games, when he did so in Rome. That year, he completed a remarkable athletic career by winning the decathlon at the 1960 Olympic Games, defeating Bruin teammate C.K. Yang in a memorable finish in Rome, Italy. His most serious rival was Yang Chuan-Kwang (C. K. Yang) of Taiwan. Yang also studied and trained at UCLA. In the decathlon, the lead swung back and forth between them.

Finally, after nine events, Johnson led Yang by a small margin, but Yang was known to be better in the final event, the 1500 meters. Johnson ran his personal best at 4:49.7 and finished just 1.2 sec slower than Yang, winning the gold by 58 points with an Olympic record total of 8,392 points. Both athletes were exhausted and drained and came to a stop a few paces past the finish line leaning against each other for support. At the age of twenty-five, Rafer Johnson had fulfilled his high school dream and earned the title as the greatest all round athlete in the world! With this victory, Johnson ended his athletic career.

He received the 1960 Sullivan Award for being the outstanding American amateur athlete of the year. Rafer was also voted "Track and Field News" world athlete of the year by the Associated Press. After the 1960 Olympics, Johnson ended his athletic career and began a new chapter of his life, appearing in films as an actor and on television as a sports commentator and announcer. He made several film appearances, mostly in the 1960s. After graduating from UCLA in 1959 Johnson got into sports announcing for a time, helping to call the 1964 Olympics from Tokyo, Japan and working for a Los Angeles television station.

Johnson worked on the presidential election campaign of United States Senator Robert F. Kennedy. He was the one to wrestle the gun from the assassin’s hand that fateful night in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel. Johnson worked full-time as a sportscaster in the early 1970s. Rafer Johnson, along with Eunice Kennedy Shriver and a small group of volunteers, founded Special Olympics California in 1968. Competition sessions were conducted at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum for 900 individuals with intellectual disabilities.

Johnson was a member of the President's Commission on Olympic Sports in the 1970s. He is a member of the National Track and Field and U.S. Olympic Halls of Fame. In 1984 Rafer Johnson was chosen to light the Olympic Flame at the Opening Ceremony of the Los Angeles Olympics. Johnson's accomplishments span far beyond the track. He worked for the Peace Corps, March of Dimes, Muscular Dystrophy Association and American Red Cross. In 1994, he was elected into the first class of the World Sports Humanitarian Hall of Fame.

Rafer Johnson was the epitome of the true athlete-humantarian. He was an excellent scholar, president of the student body, has been recognized for his community service efforts and work with youth, and one of the greatest of Olympians. As a tribute to his stellar performance in the 1960 Olympics, Rafer Johnson was chosen to ignite the Olympic Flame during the opening ceremonies of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. In November 2014, Johnson received the Athletes in Excellence Award from The Foundation for Global Sports Development, in recognition of his community service efforts and work with youth.

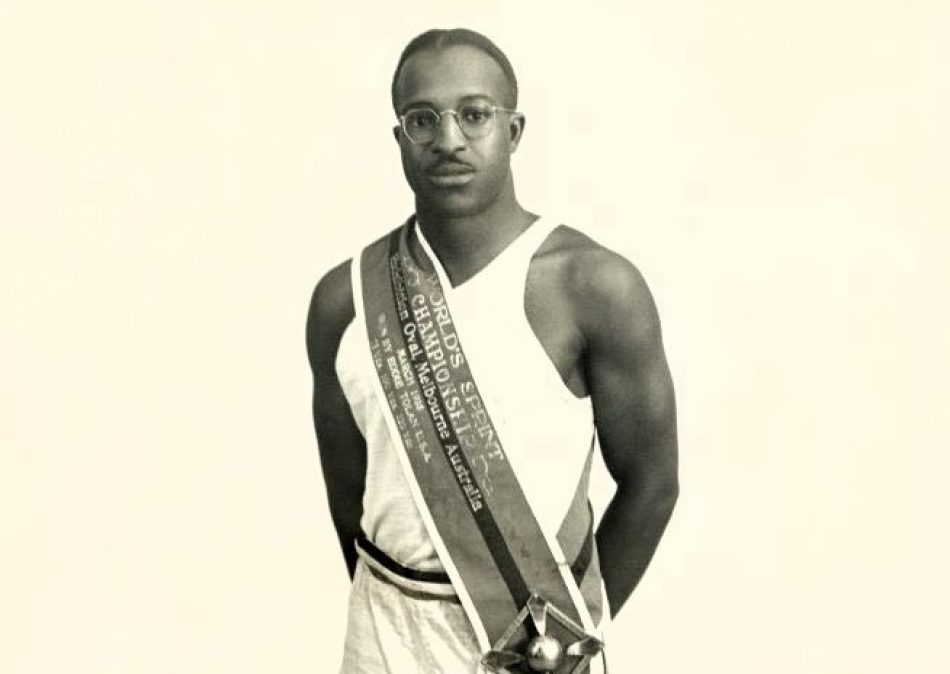

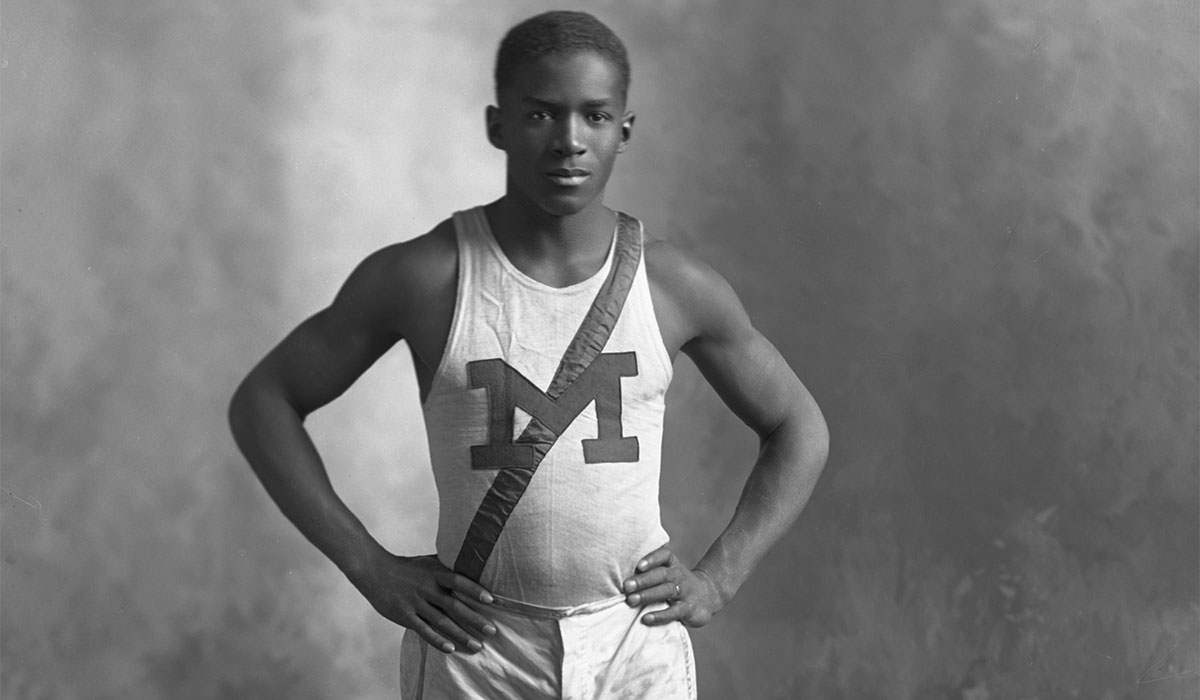

Eddie Tolan

Known as known as “The Midnight Express” he snagged two gold medals in the 100-meters and 200-meters events at the 1932 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, setting world and Olympic records. Eddie Tolan was born September 29th 1909 in Denver Colorado. Born in 1908, he moved with his family from Salt Lake City to Detroit in 1924 for better employment opportunities. A phenomenal athlete, Tolan attended Cass Technical High School, and excelled as a quarterback on the football field and a sprinter on the track and field team.

In his sophomore year of high school, he finished second place in the 50-yard dash at the first indoor scholastic meet at the University of Michigan. He blossomed into a track phenom during the outdoor season, tying the city record in the 100-yard dash with a time of 10.2 seconds and setting a city mark in the 220-yard at 23.1 seconds. Tolan was part of a two-man team that went on to win the 1925 National Interscholastic Indoor meet in Chicago winning the sprint double (100-yard and 220-yard dashes).

At the Michigan High School Athletic Association (MHSAA) championship meet, he won both the 100- and 220- yard dashes. Tolan’s senior year witnessed continued success. He won the 50-yard run at the Third Annual Indoor Meet at U-M; the 100- and 220-yard dashes at U-M’s Outdoor Interscholastic Meet; and the 100- and 220-yard races at the MHSAA championship with times of 9.8 and 21.9 seconds, respectively. During his Cass Tech career, the up-and-coming star compiled a remarkable, 94% win record in city and state individual outdoor championships.

Despite his earlier injury, Tolan was recruited by several major universities for football, in addition to track. He went on to attend the University of Michigan and intended but did not play football, however he excelled on the track. As a sophomore in 1929, Tolan broke the Big Ten Conference record and tied the world’s record for the 100 yard dash at 9.5 seconds. At the Big Ten championship in May of the following year, Tolan— then a junior—came in second place in the 100-yard dash behind the Ohio State University’s George Simpson, earning him the nickname “Midnight Express.”

Although Tolan experienced success as a sprinter in 1929 and 1930, it was the 1931 season—in which he dominated the Big Ten—that solidified his new nickname. He won the outdoor 100-yard dash in 9.6 seconds and 220-yard dash in 20.9 seconds at the championships. By the time he graduated from U-M, Tolan had competed in 100 races, losing only nine times. He was elected AAU All-College and All-American in the 220-yard dash. In addition to his involvement in collegiate athletics, Tolan became a member of the Black fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha.

After graduating from U-M, Tolan enrolled in graduate school at West Virginia State College. The program aimed to prepare students for teaching and coaching in America’s segregated education system. Tolan coached track at the school, which enabled him to stay in shape for the upcoming Olympics. At the Olympic trials at Stanford University, he finished second to Ralph Metcalfe in the 100- and 200-meter dashes. Their first and second-place finishes at the trials also meant that the top two American Olympic sprinters were, for the first time, African American.

On August 3, 1932, at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, Tolan, with horn-rimmed glasses affixed to his head and a mouthful of chewing gum, broke the Olympic record in the 100 meter race with a time of 10.38 seconds. The first of his two Olympic gold medals. The end of the race came down to a photo finish between Tolan and Metcalfe, the latter of whom was originally announced the winner. In the days before technology could solve such disputes, Metcalfe was convinced the race had been a dead heat and maintained as much for the rest of his life.

In the 200-meter run, Tolan won over George Simpson, with Metcalfe finishing third. The Michigander’s 21.2-second time earned him his second gold medal, as well as another Olympic record. With two golds, Eddie Tolan became the first double Olympic sprint champion in 20 years, and he claimed the title of “World’s Fastest Human”—the first time a Black man had been given that label. The media coverage of Tolan’s Olympic triumph, however, was marred by racism. The American media referred to him as the “dusky Negro,” or “the chunky Detroit Negro,” among other phrases.

Michigan, and the city of Detroit, responded with a welcoming reception at the train station, and Governor Wilbur M. Brucker declared September 6, 1932 as Eddie Tolan Day. Unfortunately, Tolan’s U-M degree, graduate work, and international fame as the world’s fastest human came without compensation or lucrative endorsements. He was broke and jobless, and the United States was in the depths of the Great Depression. To an American society steeped in racism, Tolan was simply a “Negro.”

Just months after returning home to an official reception, he gave up his amateur status to appear in vaudeville with tapdancer Bill "Bojangles" Robinson to earn some much-needed money to support his family. However, Tolan was soon ruled to be in violation of amateur athletic laws for using his track fame to earn an income. The AAU stripped him of his status in June 1933. Tolan became a professional sprinter in November 1934. He left his job at the Registrar of Deeds office to compete in Australia.

After setting records in Australia including events at the World Professional Sprint Championship, in March 1935, Tolan returned to Detroit. As a career sprinter, Tolan became the first man to win both amateur and professional championships. Tolan returned to his job as a Clerk with the Registrar of Deeds, and worked a variety of jobs in the 1940s and 50s. He became a physical and health education teacher and taught at Irving Elementary School on Detroit’s West Side for several years.

Tolan would oftentimes visit with coaches and track runners at his alma mater, Cass Tech, where he offered friendly advice to the young athletes. However, despite being a track star in high school, a former collegiate coach, a two-time Olympic gold medalist, and the only sprinter to win both amateur and professional championships in history, Tolan was not allowed to coach high school track. Yet when he died at the age of 57, in 1967, his legacy as a torchbearer for high-achieving Black sprinters everywhere remained assured.

Audrey Patterson

Audrey Patterson is the first Black woman from the U.S. to win an Olympic medal. She won bronze in the 200-meter dash at the 1948 Olympics, the first Games to include the race for women. Audrey Patterson was born on September 27, 1926 in New Orleans, Louisiana, in the heart of the Jim Crow south. She developed a love of running during elementary school. Audrey Patterson said she felt that “love” when 1936 Olympic gold medal winner, Jesse Owens, was speaking to school in 1944 when he told a group at Gilbert Academy, “There is a boy or a girl in this audience who will go to the Olympics.”

In 1947, Patterson enrolled at Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, where she became a track star, winning the Tuskegee Relays in the 100- and 220-yard dashes and the Amateur Athletic Union National Indoor Title in the 220-yard event. She received a scholarship to Tennessee State University and competed under Tom Harris. He was brought in after coach Jessie Abbott resigned and also recruited Ed Temple. Temple eventually took over the team. Patterson transferred from Wiley College in Texas, where she dominated the 100 meter and 200 meter races at the Tuskegee Relays, to start her short career as a Tigerbelle in the spring in 1948.

Patterson went to Providence, Rhode Island, for trials in the 1948 Olympics and earned a position on the U.S. Women’s All-American Track & Field Team for the London Olympics. Audrey Patterson was one of the nine Black women in total who competed for Team USA in 1948, including fellow Tigerbelles Emma Reed (long jump) and Mae Faggs (200 meter). This was the start of a Tennessee State legacy of Olympic success that would continue throughout the next decades. The 1948 U.S. Olympic Trials were successful, but also unlucky for Audrey.

She burned her leg with an iron before the 200m qualifying races. She won her heat, returned to the dressing room, and accidentally got locked in. Her coach heard her crying and found her just in time for the next race. Audrey also qualified in the 100m, coming in second for the first time since high school. Audrey Patterson, also known as Mickey, was a 22-year running beauty, who got cheers whenever the crowd caught a glimpse of her. And Mickey did not disappoint her international fans. Audrey Patterson became was the first African-American woman to win an Olympic medal, taking the bronze in the 200 meters in the 1948 London Olympics.

She won her Olympic medal, covering the 200 meters in 25.2 seconds, the same time as Shirley Strickland of Australia. It took officials 45 minutes to decide that Miss Patterson would get the third place bronze medal. This was the first Olympic Games that offered women the 200-meter race for competition. Fanny Blankers-Koen of the Netherlands won the race, her third gold medal. The following day, her teammate Alice Coachman won the high jump and became the first Black woman to win an Olympic gold medal. No other American woman left London with a track and field medal.

Patterson and Alice Coachman were the only women of Team USA track & field to medal during the 1948 Games. Audrey’s return home to the South from the 1948 London Games was similar to teammate Alice Coachman’s experience. Audrey was celebrated by the local Black community, and largely snubbed by the Whites. Her hometown newspaper, The Times-Picayune, did not mention her victory. The mayor did not attend her celebration ceremony, sending a certificate in his stead. However, President Harry Truman invited Patterson to the White House for a congratulatory visit after her history-making Olympic performance. Paterson eventually transferred to Southern University in Baton Rouge to finish her degree.

Bob Beamon

Olympic gold medalist and record-breaking track and field star Bob Beamon was born on August 29, 1946, in Queens, New York. He was orphaned before he was eight months old. Beamon’s stepfather was by all accounts an abusive drunk who terrorized his wife and children until it landed him in prison, forcing young Bob to live with his grandmother. The violent chaos of Beamon’s world ushered him into one of the many gangs that roamed the streets of Queens. During a fight at school, Beamon struck a teacher and slapped with an assault and battery charge.

In lieu of jail time, however, he was sent to a school for juvenile delinquents – where, among other things, he learned how to read when he wasn’t borrowing shoes to compete in athletics meets. When he was allowed to return, he used sports as a means to focus his attention and energy toward positive goals. He regularly broke track records at the local and state levels. When Beamon was attending Jamaica High School, Larry Ellis, a renowned track coach, discovered him. He didn’t seem a serious prospect, initially. “I wanted to be a Globetrotter,” says Beamon.

In 1965, Beamon set a national high school triple jump record and was second in the long jump. He further distinguished himself at the Penn Relays as the outstanding competitor in the high school division. Beamon later became part of the All-American track and field team. Beamon began his college career at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University (North Carolina A&T). He then transferred to the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP), where he received a track and field scholarship.

UTEP had just made history by beating uber-White Kentucky in the 1967 NCAA basketball championship. That same year, Beamon won the AAU indoor high jump title. He earned the silver medal in long jump at the 1967 Pan American Games. It looked as if he’d cruise into Mexico City. But then, Beamon along with eleven other Black athletes were dropped from the (UTEP) track and field team the week following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. for participating in a boycott of competition with Brigham Young University.

They had banded together ahead of a meet against the Latter-day Saints school to protest against what they characterised as the Book of Mormon’s racist teachings. “It was a very sad and dark time,” says Beamon, recalling how he was radicalised during this period of national tumult. “I became aware of the Ku Klux Klan and other racial outbursts. Black people were becoming more aware, especially of who we were as individuals. We started wearing afros, talking about Black power, Black pride, Black is beautiful.”

Beamon’s stand cost him his scholarship, and momentum. Despite losing his athletic scholarship, Beamon returned to UTEP to continue his studies after the Mexico City Olympics. "He lost the concept of the long jump,” 200 meter Bronze medal John Carlos says. So my thing was to work with him on his speed, and then when I felt he was strong enough, I told him to get with [US coach and fellow jumper] Ralph Boston to get his steps down. Fellow Olympian Ralph Boston became his unofficial coach.

By the time the Olympics came around, it was October – the event pushed back to avoid Mexico’s rainy summer season. Beamon entered the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City as the favorite to win the gold medal, having won 22 of the 23 meets he had competed in that year. They included a career-best of 8.33 meter (27 ft 3 in) and a world's best of 8.39 meter (27 ft 6 in). Beamon came close to missing the Olympic final after fouling on his first two qualifying jumps. With only one chance left, Beamon re-measured his approach run from a spot in front of the board and made a fair jump that advanced him to the final.

There, he faced the two previous gold-medal winners, fellow American Ralph Boston (1960) and Lynn Davies of Great Britain (1964), and twice bronze medallist Igor Ter-Ovanesyan of the Soviet Union. With a few gentle rocks, Beamon eased down the runway in a long, upright stance, pogoed into thin air and hung there as the crowd held its breath. A roar broke out when he finally touched down in the sand pit, well outside the range of an optical device that had been trotted out to precisely log all the jumps.

Ultimately, the judges were forced to break out their old measuring tapes. When the mark of 8.9 meters appeared on the scoreboard, Beamon, a product of the imperial system, had no idea what that meant. Just 22 years old, he landed a jump of 29 ft. 2 1/2 inches (8.90 meter), destroying the existing world record by 55 cm (21+3⁄4 in) or by 1.9 feet. That is almost two feet! When the announcer called out the distance for the jump, Beamon, unfamiliar with metric measurements, wasn't affected by it.

When his teammate and coach Ralph Boston told him that he broke the world record, an astonished Beamon collapsed to his knees and placed his hands over his face in shock. Before Beamon’s golden attempt, the long jump world record had been broken 13 times since 1901. An increase of more than 15cm was thought to be superhuman. In one of the more enduring images of the 1968 Olympic games, his competitors then helped him to his feet.

Within hours of winning Olympic gold, Beamon was back in class at El Paso. No parade. No welcome wagon. No nothing. “I walked into class and they said, ‘Open your book to page one,’” he says. Without warning, he hung up his jumping cleats just before the Munich Olympics in 1972. “People were saying, You need to go back. But what for? I had already proven that I’ve done something, that I’ve won a gold medal in the long jump. Now I needed to transition into something that, to me, would be just as exciting.”

Shortly after the Mexico City Olympics, Beamon was drafted by the Phoenix Suns in the 15th round of the 1969 NBA draft but never played in an NBA game. Beamon is in the National Track and Field Hall of Fame. In 1972, he graduated from Adelphi University with a degree in sociology. Beamon's world record stood for 23 years until it was finally broken in 1991 when Mike Powell jumped 8.95 m (29 ft 4.23 in) at the World Championships in Tokyo, but Beamon's jump is still the Olympic record. Powell broke Beamon's record by a mere 2 inches.

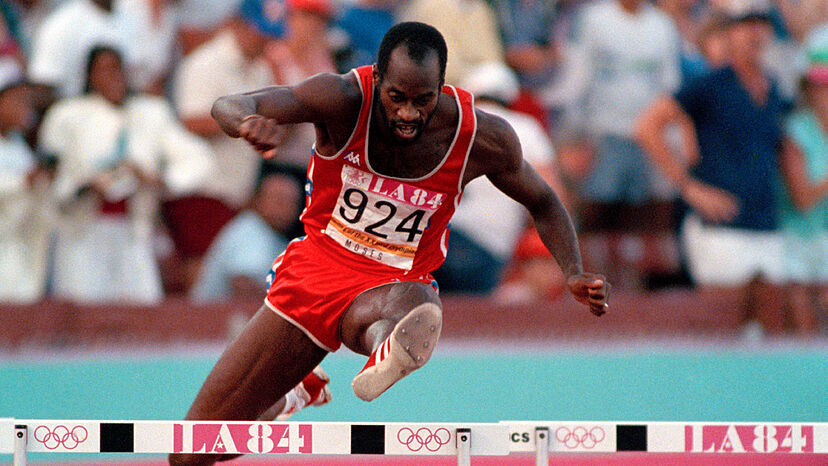

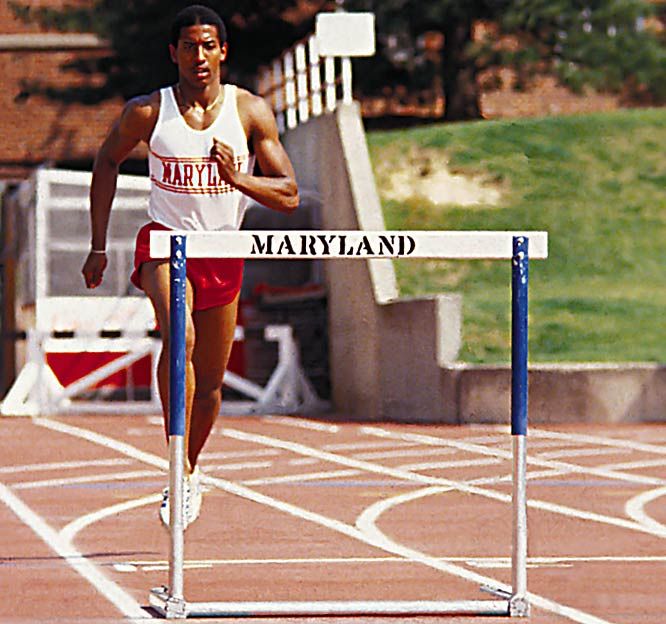

Edwin Moses

Edwin Moses, dominated the 400-meter hurdles event for a decade, winning gold medals in the race at the 1976 and 1984 Olympic Games. Edwin Corely Moses was born on August 31, 1955, in Dayton, Ohio, the second of three sons to parents who were both educators. When his high school basketball coach cut him from the team and the football coach kicked him out for fighting, Moses turned to track and gymnastics. At a young age, Moses was a lot smaller than the other runners.

In high school, he was 5-feet-7 tall and weighed 117 pounds and frequently found himself at the back of the pack during races. But as he grew physically, he got faster and progessively found himself leading races, rather than trailing. He was a serious student, even foregoing potential athletic scholarships to college in favor of attending Morehouse College in Atlanta. When Moses attended Morehouse from 1973 to 1978, there was not even a track. The track team had to run in the streets or go to Washington High School or Lakewood Stadium to practice.

When Moses entered Morehouse, he said he was not “recruit able” as an athlete because he was a “late bloomer” and was still growing into his body. So, he focused on academics, earning a degree in physics. Moses and his classmates had to improvise his practice by having him jumping over fences or jumping over chairs and garbage cans in their dorm’s hallways. A physics and engineer major – used math to calculate that he needed to take exactly 13 steps between hurdles to maximize efficiency in the 400-meter hurdles.

As a 20-year-old, unknown scholar-athlete from a renowned Black college, he burst upon the international track and field scene. In March of 1976, Moses competed in the Florida Relays in the 110-meter hurdles, the 400-meter hurdles and the 400-meters flat. He qualified for the Olympic trials in all three events. In 1976, as a 20-year-old, unknown scholar-athlete from a renowned Black college, he burst upon the international scene at the Montreal Olympics. Not only did Edwin Moses win the Olympic trials in the 400 meter hurdles, he also set an American record of 48.30 seconds.

At his first Olympics, the 1976 Montreal Games, Moses won the 400 meter hurdles in an Olympic and World Record time of 47.63 breaking John Akii-Bua's mark of 47.82. His eight-meter victory over Mike Shine was the largest winning margin in the event in the Olympics. Despite being the only American male track athlete to win an individual gold medal, Moses was not received with warmth by the public. Perhaps it was because of his serious expression, modified Afro, dark glasses and rawhide thong necklace.

At Morehouse, where he basically coached himself, Edwin Moses was known as "Bionic Man" due to his improbable, fierce workouts. He took a scientific approach to analyzing his performance and developing his training methods. The method paid off in his breaking his own world record with a 47.45 at the Pepsi Invitational, an AAU meet, in 1977. On Aug. 26, 1977 in Berlin, Edwin Moses lost to Harald Schmid, his fourth defeat in the 400 hurdles, his last loss for almost a decade. Moses then won 122 straight races between August 1977 and May 1987.

The United States boycotted the 1980 Olympic Games held in Moscow, where he likely would have captured another thereby denying Moses a second golden opportunity. However, later that year he demonstrated his excellent form in Milan, Italy when he smashed his World Record of 1977 with a new record time of 47.13 seconds. Also in 1980, Moses openly challenged the hypocrisy of the rules that prohibited amateurs from accepting money for competing and making endorsements. He believed that everything should be above-board rather than under-the-table.

Three years he broke the world record for the fourth time on his 29th birthday in Koblenz, West Germany, with his time of 47.02. During the early 1980s Edwin Moses began to speak up on controversial issues. A less popular topic among athletes, Edwin Moses also spoke out against the use of steroids and ways to improve drug testing. He recognized the disastrous affects of these drugs by athletes, could cast upon the sport of Track and Field. "Somebody had to say something," he said. "What are these people doing to their bodies? Is winning worth that price? I don't think so."

After missing the 1982 season because of injury and illness, Moses came back the next year and had the race of his life. In 1983, he won his first world title at the first World Championships at Helsinki, Finland. On that day, his 28th birthday, Moses raced to another world record, 47.02. Moses defended his Olympic title at the 1984 Games in Los Angeles. He became the second man to win two 400 hurdles. Getting off to a quick start, he won in 47.75 seconds.

Moses’ winning streak came to an end in 1987 when he finished second to Danny Harris. On June 4, 1987, in Madrid, in their first head-to-head confrontation since the Olympics, Harris ran a 47.56 to beat Moses by .11 seconds. Moses had won 122 consecutive races, set the world record twice more, won three World Cup titles, a World Championship gold, as well as his two Olympic gold medals. The closeness anyone has come to matching 122 consecutive victories in track and field is Carl Lewis's 65 straight long jump wins.

After that defeat, Moses won 10 straight, including beating Harris at the 1987 World Championships in Rome. He leaned across the finish line in 47.46 to nip Harris and Schmid by about six inches. At the Seoul, South Korea, 1988 Olympic Games, Moses took bronze in the 400-meter hurdles, 47.56 sec, even though his time was faster than his gold medal runs in 1976 and 1984. Moses retired from track afterward but took up bobsledding and won the bronze for two-man teams in a 1990 World Cup race in Germany.

Moses finished seventh at the 1991 World Championships. In 1994, Moses received his Master's from Pepperdine and was elected into the U.S. Track and Field Hall of Fame. Since 1997 he has been president of the International Amateur Athletic Association. He currently serves as chairman of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, a job that puts him on the front lines of a program to help Olympic athletes evade positive tests. He was responsible for the development of drug control policies and procedures as Chairman of the Substance, Abuse, Research and Education organization.

Edith McGuire

The youngest of four children, Edith McGuire was born in Atlanta, Georgia on June 3rd 1944. Athletic from an early age, Duvall’s first experience with track and field started during an elementary school’s May Day celebration. McGuire started taking track more seriously during high school at Archer High School in Atlanta. McGuire excelled at academics and sports and was consistently on the honor roll. McGuire was coached by Mrs. Marian Armstrong-Perkins. Coach Armstrong-Perkins had a prestigious reputation for training Olympic athletes, and since 1952, she had at least one former student competing on the U.S. Olympic team.

At the age of 15, she defeated the top prep-school sprinter in Atlanta. As a result of her outstanding performance, in 1960 Coach Armstrong-Perkins recommended Duvall attend Coach Edward Temple’s summer track and field training camp at Tennessee State University in Nashville. McGuire would earn herself a scholarship to Tennessee State in 1961. As a high school senior, McGuire won AAU championships in both the 50-yard and 100-meter dashes. She began in the fall of that year and majored in elementary education.

Edith McGuire became one of the top sprinters of the 1960s, winning six Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) championships. Tennessee State had a very successful women’s sprinting team in the 1960s, known as The Tigerbelles, which included Olympic champions Wilma Rudolph, Wyomia Tyus, and McGuire. She made her international entrance in 1963 at the Pan-American Games in São Paulo, Brazil. McGuire took first place in the 100-meter dash and 400-meter relay. These successes led her to the 1964 Olympic Games held in Tokyo, Japan.

She ran against fellow TSU Tigerbelle and close friend, Wyomia Tyus, considered one of the fastest sprinters in the world, in the 100 meter. She was also going against Irena Kirszenstein and Ewa Klobukowska from Poland, who had recently beaten Tyus’s and Wilma Rudolph’s 100-meter time. McGuire came in second to Tyus for a close upset and a silver medal. However, Edith McGuire achieved her fame at the 1964 Tokyo Games, with her gold medal in the 200 meter, in which she set an Olympic record of 23.05, capping an undefeated season in that event.

McGuire would also win a silver medal as part of the 400-meter relay team with Tyus and two other Tigerbelles. After her wins in Tokyo, Edith became the second African American woman to win three medals in the same Olympic Games. In recognition of her Olympic achievements, McGuire was a top ten finalist for the Sullivan Award. Established by the AAU in 1930, the Sullivan Award is presented annually to the amateur athlete chosen as doing the most “to advance the cause of sportsmanship.

She also came in fourth in the national ballot for Sportswoman of the Year. When McGuire graduated from TSU in 1966, she also retired from competitive track and field as a six time AAU-All-American. She was honored by inductions into the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame (1975), the Track and Field Hall of Fame (1979), and the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame (1980). McGuire received the 1991 National Collegiate Athletic Association’s Anniversary Silver Award in Nashville.

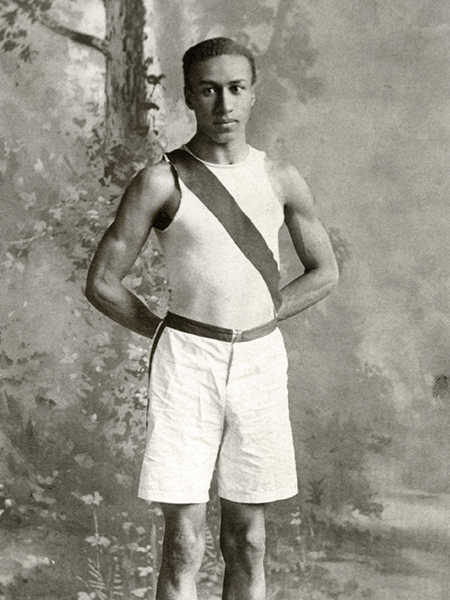

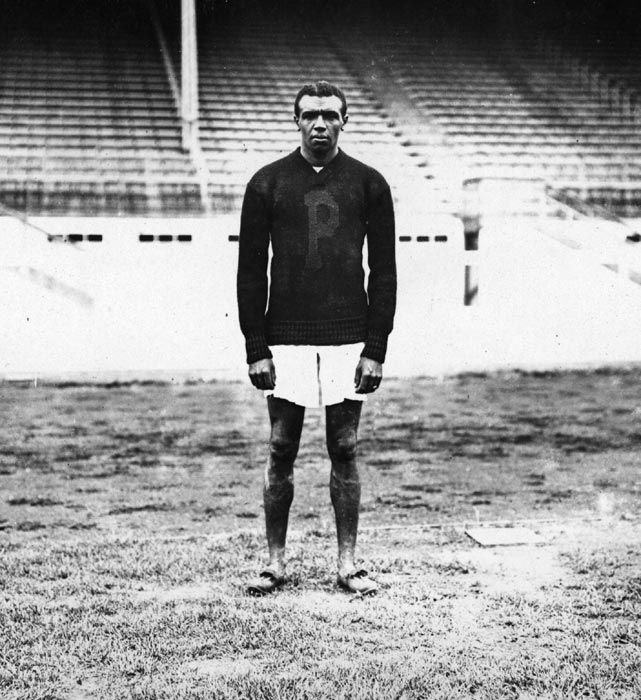

George Coleman Poage

Born in Hannibal, Missouri on November 6, 1880, George Coleman Poage move to La Crosse, Wisconsin when he was 4-years old. In 1884, his family moved from Hannibal, Missouri to La Crosse, Wisconsin. Young George Poage was a good student and a good athlete. As a teen, he attended La Crosse High School where his love for athletics grew. Poage received his high school diploma in 1899 and decided to continue his education at the University of Wisconsin. He later joined the University of Wisconsin. Poage also was the first African American to run and graduate from the school.

In 1900, his first track race was against the freshman track squad at the university. He then made the varsity team his sophomore year. He consistently won points for the Badgers in his specialized events, short sprints and hurdles, quickly gaining the respect of his team mates. After graduating in 1903 with a degree in history, Poage returned to UW to take graduate classes and continue running track. The athletic department helped support Poage’s extra year on campus by hiring him to be a trainer for the football team. He continued to break barriers and set records as an athlete.

In 1903, he became the first African American Big Ten track champion (individually) by placing first in the 440-yard dash and the 220-yard hurdles. In 1904, the third Olympic Games were being held in St. Louis in conjunction with the World’s Fair. The 1904 Olympic games were far smaller than they would become. Only 496 athletes from 11 countries competed, and just 20,000 spectators attended track and field events. Poage was running for the Milwaukee Athletic Club; he was its first non-White competitor when he won bronze medals for finishing third in the 200-meter and 400-meter hurdles.

Before the games began many prominent African-American leaders called for a boycott of the events in St. Louis. The organizers of both the Olympics and the World’s Fair had constructed Jim Crow facilities for their spectators. They would not allow an integrated audience to view the spectacle. During times of nationwide segregation and an intense struggle for racial equality, Poage managed to qualifiy for the 1904 Summer Olympics with the sponsorship of The Milwaukee Athletic Club. Despite calls for Black athletes to avoid the games, Poage decided to compete.

Poage made history when he became the first African American to win a medal at the Olympics. He would not only become the first Black Olympic competitor, he would also become the first Black medalist. He took home the bronze medal in the 200-yard and 440-yard hurdles. That same day, the second Black Olympian, American Joseph Stadler, won a silver medal for the high jump. However, after the glow of his Olympic achievements faded, and despite his education and skills as a world-class athlete, Poage couldn’t find a job, thanks to Jim Crow.

Poage returned to St. Louis to teach at segregated Sumner High School, where he was the head of the English department and helped coach the school’s sports teams. At the height of the Jim Crow era, however, there were few job opportunities in Chicago open to an African-American, even a college-educated former world-class athlete. The best employer available to many Black Chicagoans was the United States Post Office. Poage secured a job as a postal clerk in 1924 and stayed on the job for nearly thirty years until his retirement in the 1950s.

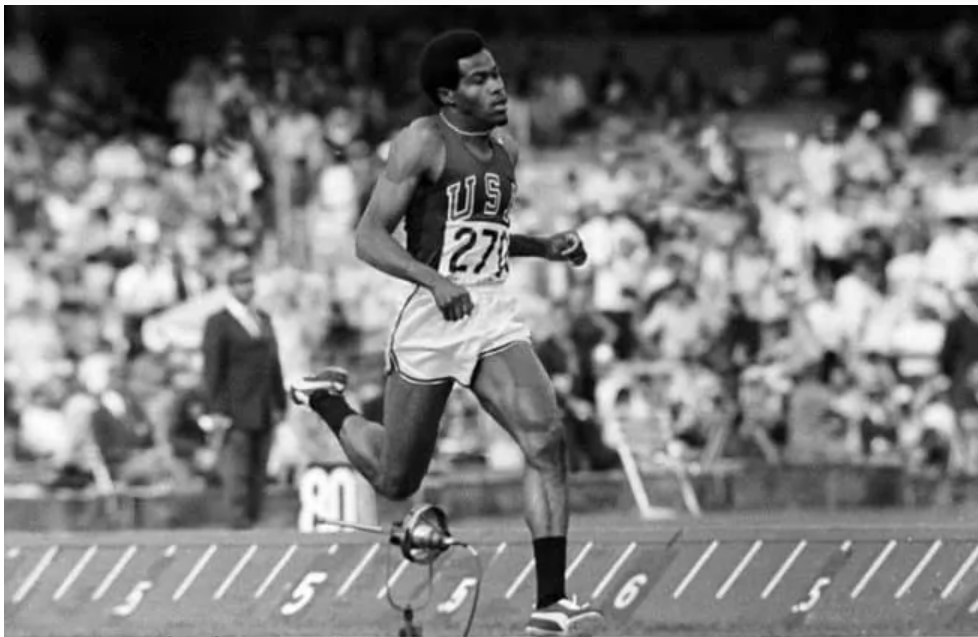

Lee Evans

He became the first man to crack 44 seconds in the 400 meters, winning the gold medal at the Mexico City Games. Lee Edward Evans was born on February 25, 1947, in Madera, California. At the age of four, his family moved to Fresno. He attended Madison Elementary School and in his last year there trained for his first race by racing his friends at school. The Evans family moved to San Jose, California, during Lee's sophomore year in high school. While running for Overfelt High School, Lee Evans went undefeated during his high school track career.

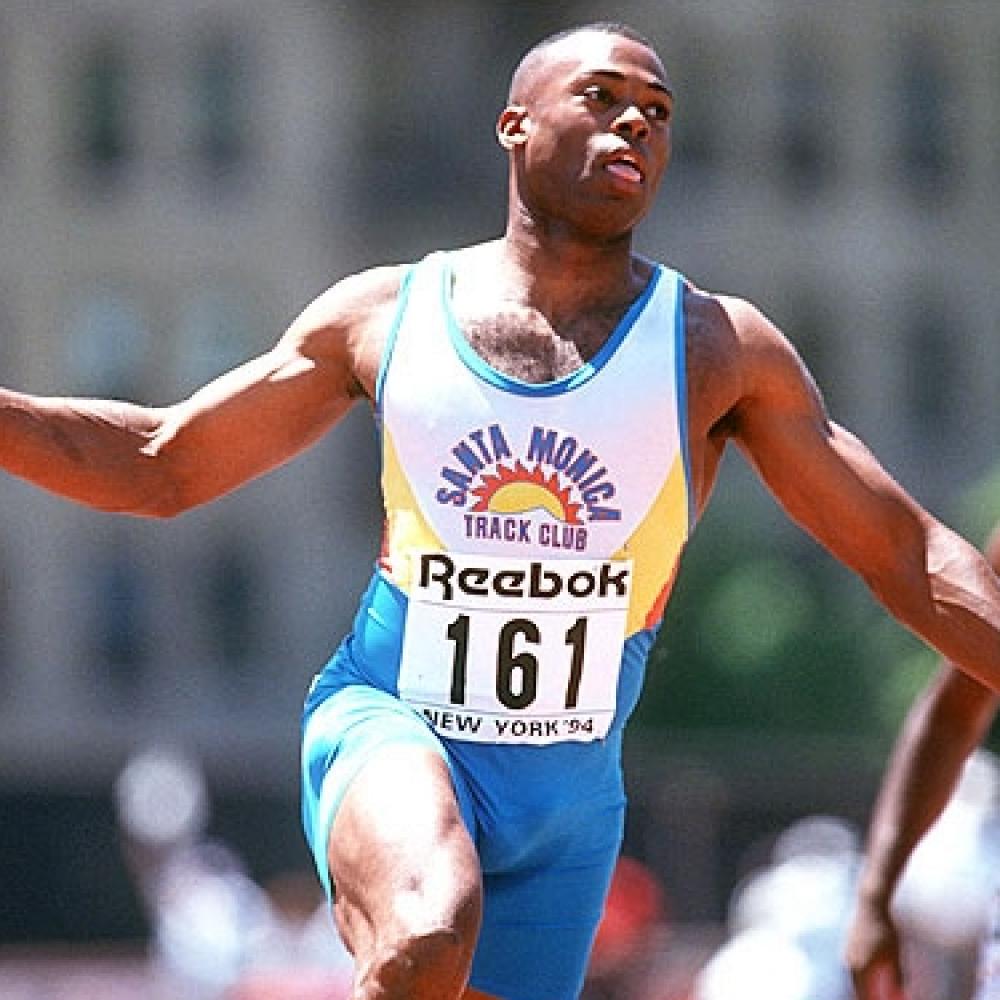

Lee improved his 440-yard time from 48.2 in 1964 to 46.9 in 1965. Evans ran for the San Jose State University track team where he was coached by Hall of Famer Bud Winter. In 1966 as a freshman, he won his first AAU championship in 440 yd. He won the AAU title four years in a row (1966–1969) and again in 1972 and added the NCAA 400 m title in 1968. His only defeat during that streak came at the hands of San Jose State teammate Tommie Smith. The two were so competitive, Winter could not let them practice together.

Evans achieved his first world record in 1966, as a member of the USA national team which broke the 4 × 400 meter relay record at Los Angeles. They were the first team to better 3 minutes (2:59.6) in the event. The next year he helped break the 4 x 220 yd (201.17 m) relay world record at Fresno in a time of 1:22.1. In 1967, Evans won the 400 meters at the Pan American Games, in a time of 44.95. This was the first time anyone has broken the 45 seconds barrier. Lee Evans was ready for the Olympics.

Evans won the 1968 Olympic trials at Echo Summit, California, with a world record 44.06. Evans wanted the world to understand the way he felt about the Mexico City Olympic Games but did not want to take away from the winners and the sports themselves. But it was at the Mexico City 1968 Olympic Games that Evans, stepped onto the world stage. The previous year he had become the first person to break the 45-second mark in the 400-meter race.

He became the first person to break 44 seconds in the 400 meter, when he set a new world record of 43.86 seconds in the Mexico City Games final. That mark stood for 20 years. The winning performances were in the shadow of controversy. Evans had considered withdrawing from Olympic competition following San José State and USA teammates Tommie Smith and John Carlos were expelled from the Olympic Village. Two days earlier, Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos finished first and second in the 200-meter race.

At the medal ceremony, they wore high black socks to the podium and, wearing a black glove, each raised one fist during the playing of the Star Spangled Banner. After the clean sweep of the medals in the 400, Mr. Evans, silver medalist Larry James and bronze medalist Ron Freeman wore black berets as their sign of support for the Olympic Project for Human Rights. Evans received death threats prior to and during the Olympics and claimed that had he not had these threats on his mind he probably could have run faster than he did, even though he broke a world record.