Boxing

It wasn't until the 20th century that nations with large immigrant populations, like Australia and the United States, held sports competitions that pitted members of one "race" against another. When Black American Jack Johnson took the heavyweight title from the Irish boxer Tommy Burns, the race issue in sports reached a new level. Some people did not believe that Black Americans had what it took to become heavyweight champions in the "manly art" of boxing. Throughout boxing history, many Black fighters have proudly stood as symbols of aspiration, success, power and resolve. Some overcame the systemic odds to become champions, while many illustrious names were denied deserved opportunities.

Whether due to his enormous talent in the ring or his ostentatious personality, Jack Johnson frightened many White Americans. To them, he not only represented the awful possibility of Black superiority, but he refused to "keep his place." He was not intimidated by White people, and he openly consorted with White women. Historian Jeffrey Sammons says, "Jack Johnson had to be the bravest man in America. I'm amazed at what he did publicly that many would not dare to do privately. In fact even looking at a White woman could be a death sentence at the time." The fear of a powerful, uncontrollable Black man remained on the minds of many when Joe Louis emerged as the next potential Black champion. Neither boxer was expressly political.

Johnson pushed the envelope of expectations, while Louis, although no champion of the status quo, looked moderate in comparison. But there is no doubt that these first Black heavyweight champions broke through the color lines in American sports. Louis had to win over White America through how he carried himself and how he performed. His managers set down rules for their young fighter, which they shared freely with reporters. Louis' public face would be the opposite of what Johnson's had been. Historian Jeffrey Sammons lists a few of Louis' "good Negro" rules:

"He could not gloat over opponents. Louis could not be seen in public with White women. He had to be seen as a Bible-reading, mother-loving, God-fearing individual, and not to be 'too Black.'"

Despite Louis' public image campaign, millions of Whites rooted against him, and awaited the "Great White Hope" who would claim boxing honors for their own race. Ultimately, though, what won Louis White America's acceptance was not his mild personality and good behavior, but his dramatic matchups with German champion Max Schmeling who, to many, represented the Nazi Party. Louis would become the symbol of American freedom over Nazi totalitarianism. Many Whites still wished to see Louis defeated by a White boxer, but in 1938, when Louis knocked out the German, the celebration wasn't confined to Black America alone. For the first time, Blacks and Whites, even in the deep South, had rooted with all their hearts for the same guy.

Throughout much of the 1940s, eight Black boxers named Charles Burley, Eddie Booker, Jack Chase, Cocoa Kid, Bert Lytell, Lloyd Marshall, Aaron Wade, and Holman Williams were heavily avoided by many other prominent boxers of the era, including Sugar Ray Robinson (who avoided Burley). Six of them never received title shots because of corrupt management and oftentimes their skin color. Instead, they had to fight each other, at times, to stay active. Lloyd Marshall, Cocoa Kid, Eddie Booker, and Charles Burley were eventually inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame (IBHOF). Presented here is a boxing timeline, a few highlights of some boxing biggest and famous bouts down through the years.

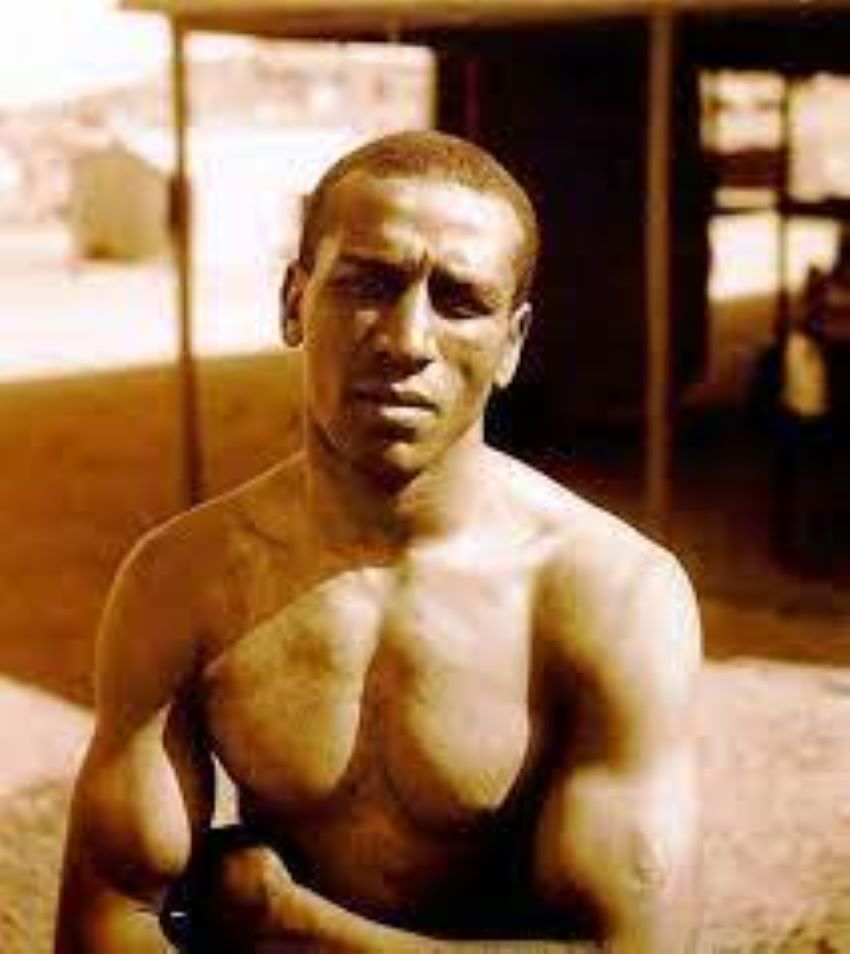

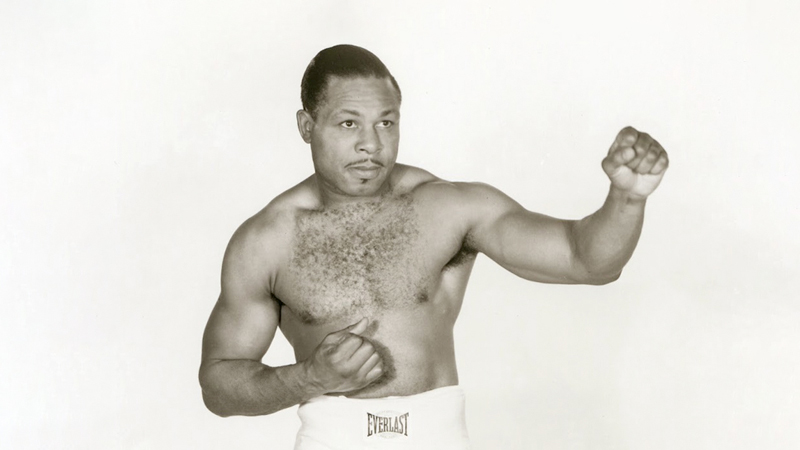

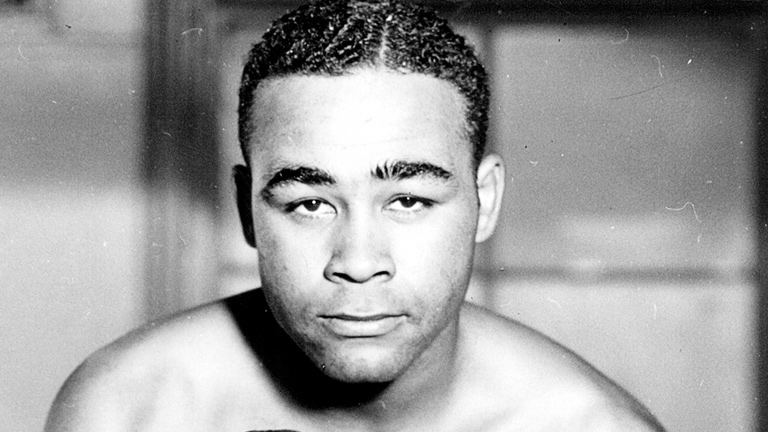

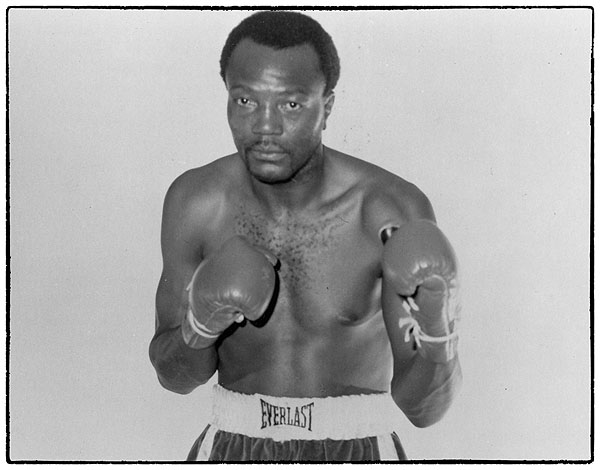

Joe Louis

Born into a poor family on May 13, 1914 in LaFayette Alabama, Joe Louis was the seventh of eight children. Looking for a better life, his mother followed the path of many southern Black families, and moved their new family up to Detroit in 1926, where factory work was plentiful. A friend took him to Brewster's East Side Gymnasium and introduced him to boxing. He fell in love with the sport.

As a teenager, Joe was the best boxer of his group. His first amateur fight was at light-heavyweight in 1932 at the age of seventeen. He lost on points after three rounds in which he got knocked down three times. But this lost did not deterred Joe Louis. At nineteen he won the National Light Heavyweight Amateur Crown of the Golden Gloves in 1933. Jack Blackburn, a very knowledgeable boxing man, was Louis's trainer. He taught Louis how to punch and worked with him to develop his body coordination.

His early career was a period of hard work and determination, and was one without glamour or fame. Louis kayoed Jack Kracken in his first professional fight on July 4, 1934. Ten years after his arrival in Detroit, Louis won the Golden Gloves as a light heavyweight. Following this win, Louis turned professional. His first professional fight took place on July 4, 1934, and he won twelve contests within the first year. His boxing prowess, as well as his reputation, was growing at an incredible rate.

In June of 1935, he fought Primo Carnera the former heavyweight champion. He beat the former world heavyweight champion with a sixth-round knockout. Later that year, Louis followed this fight with a pairing against Max Baer, who he defeated by knockout in the fourth round. Former heavyweight champion Max Schmeling was on the same path to reclaim his title. The Schmeling and Louis camps agreed to a bout in 1936. Louis sustained his first professional loss in 1936 at the hands of Max Schmeling, by a knockout in the 12th round.

In 1937, after the downfall to Schmeling, Louis returned to training with a renewed purpose -- to defeat Schmeling. Schmeling and Braddock had arranged a title match, but as Adolf Hitler made headlines and threatened war, anti-Nazi groups and unions promised a boycott, scaring off the promoter. Braddock's management found they could make more money with less controversy by setting up a match with Louis. Louis fought Jim Braddock for his chance to become heavyweight champion of the world.

He knocked out James J. Braddock in eight rounds in Chicago. With his win, he became only the second Black boxer to hold the title. In the early twentieth century, the color line was often drawn in boxing, especially in the heavyweight division. However, while the first, Jack Johnson was hated by White America, Louis would win the hearts of the whole country and be seen as a national hero. Then, in 1938, Louis met Schmeling in a rematch. The American media portrayed the fight as a battle between Nazism and democracy.

Louis’s dramatic knockout victory in the first round made him a national hero. He was perhaps the first Black American to be widely admired by White America. Louis was at his peak in the period 1939–42. From December 1940 through June 1941 he defended the championship seven times. After enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1942, he served in a segregated unit with baseball great Jackie Robinson. It was on December 5, 1947, where Louis met Jersey Joe Walcott, a 33-year-old veteran with a 44-11-2 record. Walcott entered the fight as a 10-to-1 underdog.

Nevertheless, Walcott knocked down Louis twice in the first four rounds. Most observers in Madison Square Garden felt Walcott dominated the 15-round fight. Yet, Louis was declared the winner in a split decision. Louis was under no delusion about the state of his boxing skills, yet he was too embarrassed to quit after the Walcott fight. After the war, the champion defended his title four more times, the last two coming against the future heavyweight champion Jersey Joe Walcott.

On March 1, 1949, he retired as the undefeated champion long enough to allow Ezzard Charles to earn recognition as his successor. In his heyday he earned $5 million, but it was mostly gone by the end of the 1940s, when the IRS hit him with a demand for $1.2 million in back taxes and penalties. As he would later put it, "When I was boxing I made five million and wound up broke, owing the government a million. If I was boxing today I'd make ten million and wind up broke, owing the government two million."

He was forced to return to the ring to pay off his debts. He fought Charles for the championship on September 27, 1950, but lost a 15-round decision. Not ready to accept defeat, he again tried his hand in 1951 against Rocky Marciano. During this unsuccessful return to the ring, he would face the up-and-coming boxer Rocky Marciano in his last-ever professional fight. A total mismatch, Marciano won with ease knocking, "The Brown Bomber" through the ropes in the 8th round in October 1951.

This marked the end of one of the most celebrated careers in boxing history. That was Joe Louis’ final time in the ring. Joe Louis was world heavyweight champion from June 22, 1937, until March 1, 1949. During his reign, the longest in the history of any weight division, he successfully defended his title 25 times, more than any other champion, scoring 21 knockouts. He knocked out five world champions and will remain a powerful part of boxing history for many decades to come. Louis was inducted into the Ring Magazine Boxing Hall of Fame in 1954 and the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.

He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1982. Joe Louis legacy is even greater, outside the ring. He did more for race relations in America than most in the pre-civil rights era. Louis is widely seen as the first Black man to be elevated to the status of national hero in the USA. He was able to get White America to support him in the ring, an achievement that opened the door for many other Black boxers. Joe Louis was a role model and proved that good sportsmanship can exist even in a sport as violent as boxing.

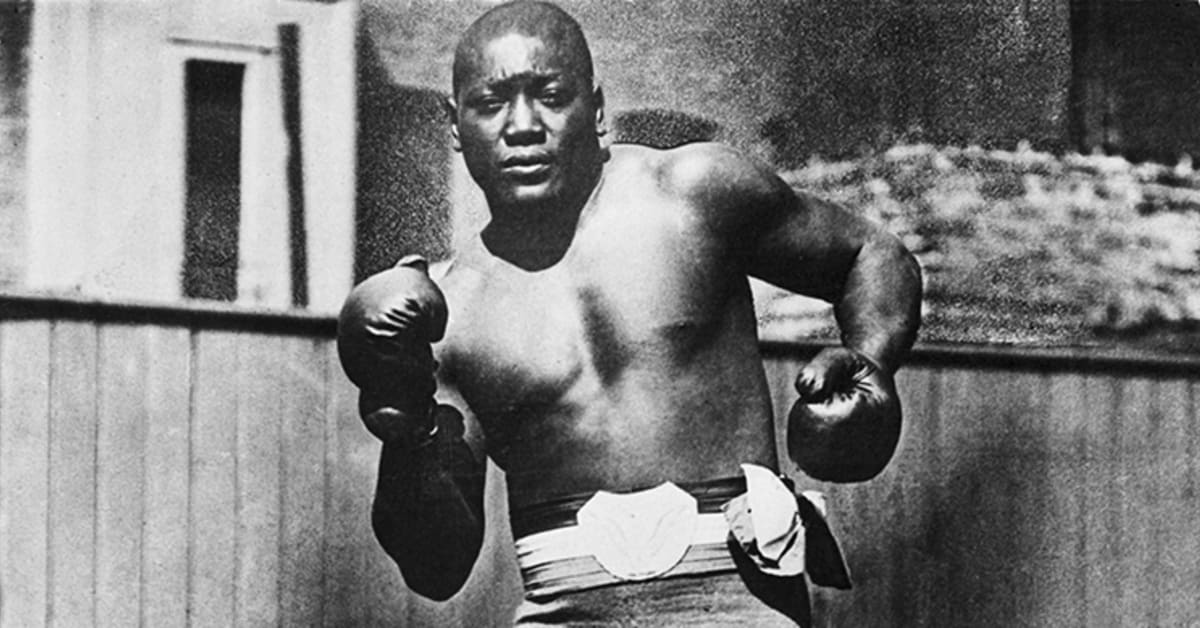

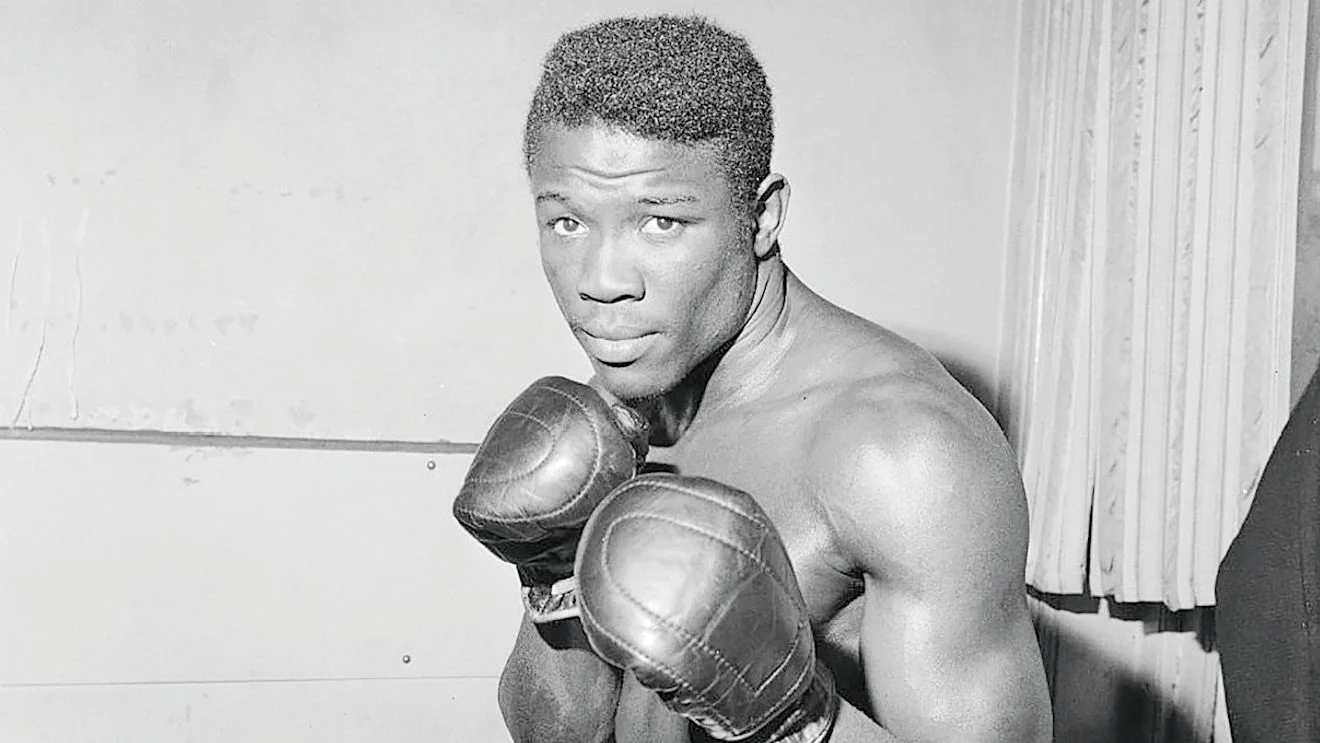

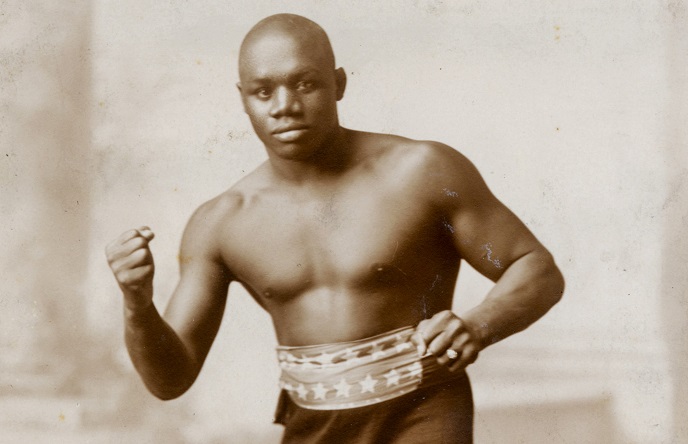

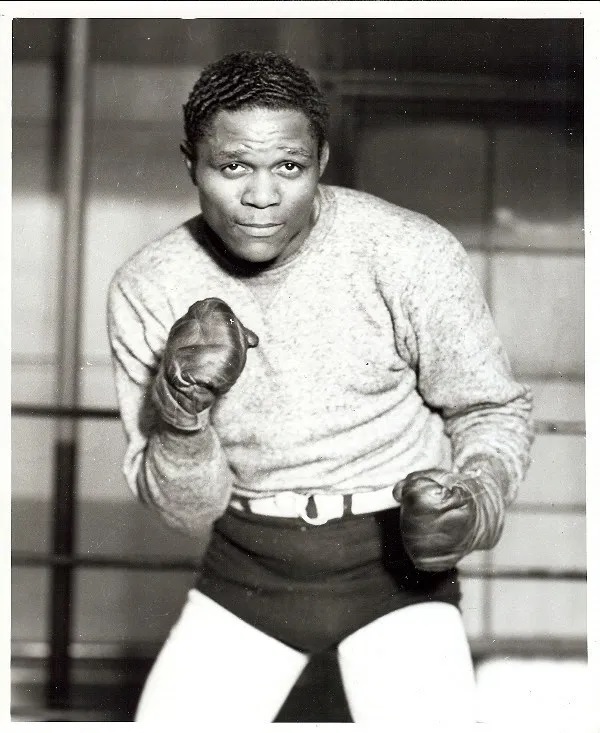

Jack Johnson

He was the first Black man to win the Heavyweight championship of the world. Jack Johnson was born on March 31, 1878 in Galveston, Texas. As a teenager, Johnson worked the docks. When Johnson was 16, he moved to New York City and lived with Barbados Joe Walcott, a welterweight fighter. He began boxing in 1897 and quickly became an accomplished and feared fighter. He began participating in local fights, eventually moving to Chicago where he linked up with his first promoter. Jack Johnson turned pro in 1897.

In 1899, he lost his first fight in a knockout defeat against Klondike Haynes. The following year, he beat Haynes, earning his first $1,000 as a boxer. As a Black fighter, he was predominately restricted to facing only Black opponents. Johnson captured the “Colored Heavyweight Championship of the World” on February 3, 1903 in Los Angeles, California. He had several notable bouts on his way to the “Colored Heavyweight Championship of the World” with Joe Jeanette, Sam Langford and other well-known Black boxers from that time.

Jack Johnson was relentless in his quest to fight for the heavyweight title. Burns initially wanted “to give the White boys a chance” first – but Johnson finally got his shot. For two years Johnson traveled around the world publicly taunting the reigning champion Tommy Burns. Finally, Johnson was given a chance for the Heavyweight Championship. He won the title by knocking out champion Tommy Burns in Sydney on December 26, 1908. The fight lasted fourteen rounds before being stopped by the police in front of over 20,000 spectators.

The title was awarded to Johnson on a referee's decision as a T.K.O, but he had clearly beaten the champion. During his title defense during this period, Johnson had a punch that was nothing short of legendary. During an exhibition match with famed boxer Stanley Ketchel, Ketchel threw a dirty punch and knocked Johnson down. Johnson got up, threw an upper-cut and knocked Ketchel out. Johnson's success in the ring made him an international celebrity and he was celebrated with ceremonies and parades in some Black communities.

Outspoken, independent, and conspicuous with his wealth, Johnson intentionally provoked racist whites as well as some African American intellectuals. When he became champion, a hue and cry for a “Great White Hope” produced numerous opponents. Author Jack London spearheaded the movement for the “Great White Hope,” a White opponent who could challenge Johnson for his title. At the height of his career, the outspoken Johnson was harshly scold by the press for his flashy lifestyle.

Most upsetting to the press and public opinion was the boxer's open challenge to society's disapproval of interracial dating and marriage to White women, which was illegal in many states. Racist boxer James J. Jeffries, who previously refused to fight him, came out of retirement to fight Johnson. He hadn’t fought for five years. Upon accepting the fight, he claimed: “I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a White man is better than a Negro.”

It was was billed as the "Fight of the Century" on July 4, 1910. It was a fight that did not turn out like many White Americans had hoped. The fight took place on July 4, 1910 in front of 20,000 people, at a ring built just for the occasion in downtown Reno, Nevada. Johnson proved stronger and more nimble than Jeffries. In the 15th round, after Jeffries had been knocked down twice for the first time in his career, his people called it quits to prevent Johnson from knocking him out. The fight caused race riots across the country, and caused widespread White humiliation.

Nearly 20 people were killed in the riots, with several more injured. The "Fight of the Century" earned Johnson $65,000 and silenced the critics, who had belittled Johnson's previous victory over Tommy Burns as "empty". Many proud Blacks cheered the fact that Jack Johnson had silenced all the hecklers and proved African Americans could be champions in even the heavyweight class. In 1912, he faced arrest for violating the Mann Act, a law aimed at combating sex trafficking.

The charge was dubious. Authorities disapproved of a Black man holding the heavyweight title, a symbol that represented masculinity at the time. Furthermore, his athletic prowess, refusal to abide by Jim Crow etiquette, and relationships with White women all caught up with him. Nevertheless, Johnson stood before an all-White jury who found him guilty and sentenced him to one year and one day in prison. After the verdict, Johnson fled to Europe. Meanwhile, he defended the championship three times in Paris before agreeing to fight Jess Willard in Cuba.

Johnson lost the heavyweight title from a knockout by Willard in 26 rounds in Havana, Cuba on April 5, 1915. In 1920, he eventually returned to the United States. Johnson surrendered to U.S. marshals, then served his sentence, fighting in several bouts within the federal prison at Leavenworth, Kansas. After his release he fought occasionally and performed in vaudeville and carnival acts, appearing finally with a trained flea act. Although, he would never fight for the heavyweight crown again, Johnson stayed active in boxing long after losing the title.

Known for his tremendous power and fighting tenacity in the ring, he was an important figure in boxing and in American culture. Admired for quick footwork and defensive acumen, the man known as the "Galveston Giant" retained the heavyweight title from 1908 to 1915. Johnson's success in the ring made him an international celebrity in his day. His legacy extends far beyond his achievements in the boxing ring. He boldly challenged the prevailing notions of White supremacy through his exceptional boxing skills and unconventional lifestyle.

By defying federal law and fleeing the country, he demonstrated his unwillingness to submit to unjust treatment. No matter the challenges, Johnson maintained an impressive career, continuing a 33-year career that included an official 54-11-9 record with more than 100 off-the-record fights and 80 wins. Even after officially leaving the ring, he continued to perform in exhibition style fights up until a year before his death at the age of 68. Jack Johnson was seen as a pivotal boxer, although controversial and well ahead of his time.

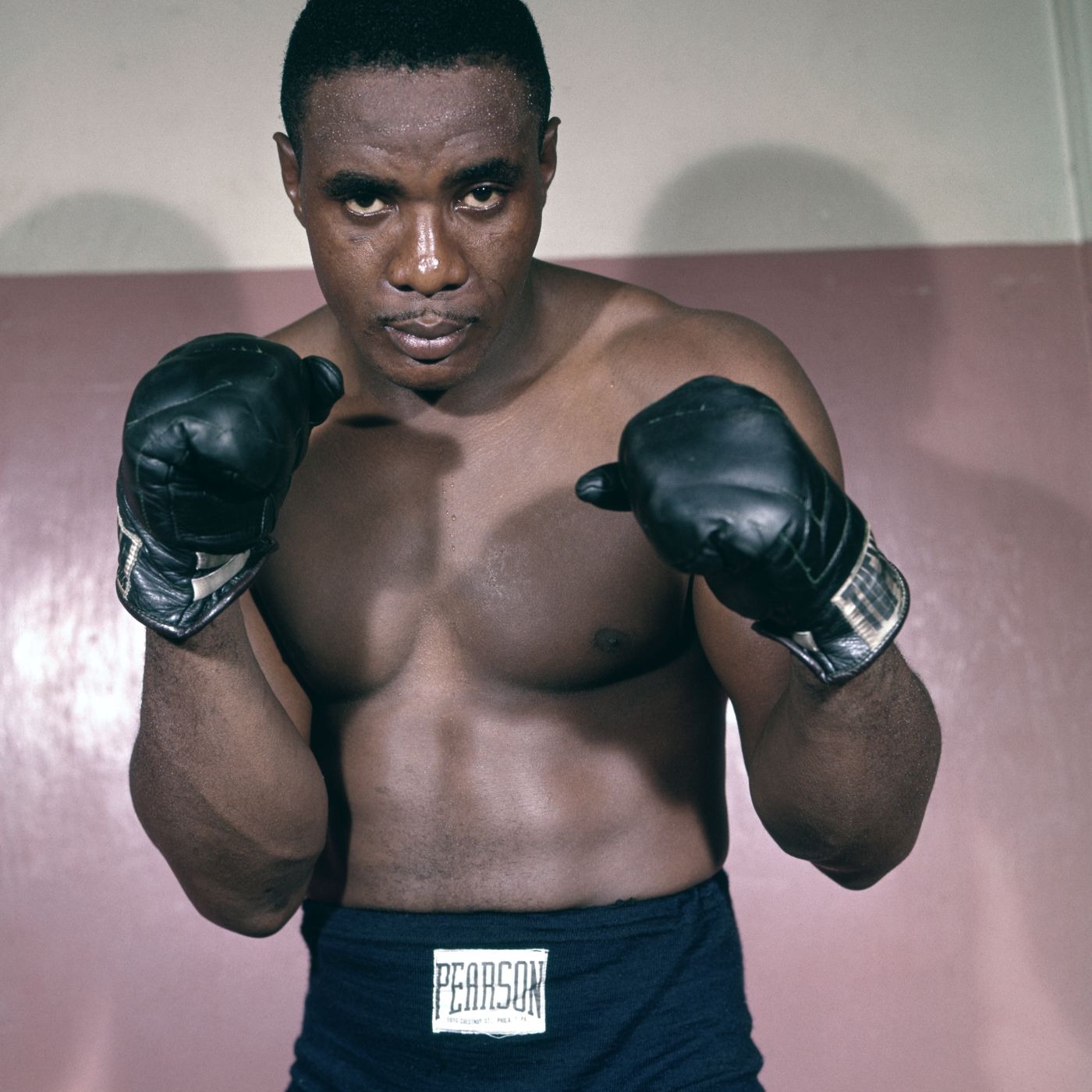

Sugar Ray Robinson

Walker Smith Jr., better known as Sugar Ray Robinson was born on May 3rd 1921. There is some confusion about his birth place. While he claims to have been born in Detroit, Michigan, his birth certificate states that Robinson was born in Alley Georgia. At an early age his father moved the family to Detroit to find work in construction. His mother made the move to New York City, after her separation, when Walker was twelve. There he would visit Times Square and dance for strangers in order to earn money to help his mother save for an apartment.

While she worked as a laundress, he also shined shoes, sold driftwood, and ran errands for a grocery store. Originally, Walker aspired to be a doctor but after three years of high school he dropped out of DeWitt Clinton High School. Walker switched his attention to boxing. He would watched boxers train at local gyms. Through a gymnasium he met George Gainford, who became his trainer and manager. Attempting to enter his first boxing tournament, Walker found out he needed to be sixteen to be granted an AAU card.

Not letting the fact he was two years too young stop him, Walker borrowed an AAU card from a friend named Ray Robinson. Sources differ as to how he got the nickname "Sugar". Some claim that future manager George Gainford watched Walker fight, he proclaimed he was "sweet as sugar". Others say that a sportswriter described him as "sweet as sugar." And there is even one source that says when a lady in the audience at a fight in Watertown, New York, saw him, she said he was "sweet as sugar."

Regardless of the source, the nickname stuck. This completed Walker Smith's transition into "Sugar" Ray Robinson." He won all his 89 amateur fights and, in 1939, the Golden Gloves featherweight title. Sugar Ray Robinson idolized certain boxers of his time, such as Henry Armstrong. However, it was Joe Louis who most captivated Robinson. Louis grew up in the same neighborhood as him when he was just 11 years old. Additionally, Sugar Ray Robinson admitted to being devastated by Joe Louis’ defeat in his fight against Schmeling in 1936, a match that left a lasting impact on him.

After winning the New York Golden Gloves championship, 19-year old Sugar Ray turned pro in October 1940 with a fight in Madison Square Garden, New York City. He went on to win his first 40 pro fights! Sugar Ray's first loss came in Detroit on February 5, 1943, at the hands of Jake LaMotta in their second of six meetings, (Robinson would win 5 of the 6). LaMotta, had a 16 pound weight advantage over Robinson. After being controlled by Robinson in the early portions of the fight, LaMotta came back to take control in the later rounds and won the ten round fight by decision.

After that defeat, Robinson wouldn't lose for another eight years. In 1942, he won a decision against former champion Zivic and future champion Marty Servo. Robinson also had a very pure boxing style and could, at any moment in a fight, become a dangerous puncher and deliver a knockout. He had the soul of a fighter, and this was evident in his style, as he possessed the technical superiority to finish a match in the early rounds.

Robinson fought many of the greatest boxers of his day, men who were at the top of their game, such as Fritzie Zivic, Kid Gavilan, Gene Fullmer, Henry Armstrong, and Rocky Graziano. By 1946, Robinson had fought 75 fights to a 73–1–1 record, and beaten every top contender in the welterweight division. On December 20, 1946, Tommy Bell and Sugar Ray Robinson fought for the welterweight title vacated by Marty Servo. The fight was called a "war," but Robinson was able to pull out a close 15 round decision.

He won the vacant welterweight title, finally becoming the world welterweight champion. Robinson was the World Welterweight Champion from 1946 to 1951. Robinson then moved on to acquiring the world middleweight title, which he held five times between 1951-1960. On February 14, 1951, Sugar Ray Robinson and Jake LaMotta met for the sixth time, this time for the middleweight title. The fight would become known as The St. Valentine's Day Massacre. Robinson won the undisputed world middleweight title with a 13th round technical knockout.

In 1952, Sugar Ray defeated former champion Rocky Graziano by a third-round knockout. During that year Robinson, challenged world light heavyweight champion Joey Maxim. At the end of round 13, he collapsed and failed to answer the bell for the next round, suffering the only knockout of his career. A few months later he retired, after 12 years of pro boxing with a record of 131-3-1. After his retirement Sugar Ray Robinson began a career in show business, singing and tap dancing, and attempting to become part of Count Basie's band.

Robinson, who lived in larger-than-life style, with a pink Cadillac convertible, fur coat, and flashy diamond jewelry, was the owner of a Harlem nightclub where jazz legends like Charlie Parker and Miles Davis played. Wherever he went, he brought a large entourage of trainers, women and family members. He was an entrepreneur when that was an unheard-of thing for African Americans to do and at a time when many African Americans were not even allowed to vote. Robinson was a shrewd businessman and hard bargainer.

Robinson returned to the ring in 1954, recaptured the middleweight title from Carl (Bobo) Olson in 1955. He lost it to and regained it from Gene Fullmer in 1957. Then he yielded it to Carmen Basilio later that year, and for the last time won the 160-pound championship by defeating Basilio in a savage fight in 1958, for a record fifth time. He lost and regained the middleweight title four times in the 1950s. A dominant force in the boxing ring for two decades, Sugar Ray was 38 when he won his last middleweight title.

Sugar Ray Robinson, more than any other Black public figure between World War II and the 1960s, epitomized Black masculinity and the cool. He was unquestionably the most admired Black male among other Black males in the 1950s. Only stopped once in over 200 bouts, Robinson's record was 175-19-6, at various weight levels. Sugar Ray Robinson was a six-time world champion, winning the Welterweight Title and then the Middleweight Title five times. He was elected to the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1967.

Henry Armstrong

After reading in a St. Louis newspaper that Kid Chocolate (Eligio Sardiñas) had beaten Al Singer, Henry Armstrong decided to become a boxer. Henry Armstrong was born Henry Jackson Jr., on December 12th, 1912, in Columbus, Mississippi. As a child, Henry Jr. moved with his family to St. Louis, Missouri. It was during the early period of the Great Migration of African Americans from the rural South to industrial cities of the Midwest and North. It was on the streets of St. Louis that young Henry first displayed a natural affinity for fighting.

He graduated as an honor student from Vashon High School in St. Louis. Armstrong worked on his athletic abilities, often running the eight miles to school. After school, he worked as a pinboy at a bowling alley. Here he gained his first boxing experience, winning a competition among the pinboys. Working at the "colored" Young Men's Christian Association, Henry Jackson Jr. met Harry Armstrong, a former boxer, who became his friend, mentor, and trainer. He later he took the surname Armstrong as his fighting name.

Early in his career, he boxed under the name Melody Jackson. Armstrong fought as an amateur from 1929 to 1932. He won his first amateur fight at the St. Louis Coliseum in 1929, by a knockout in the second round. After several more amateur fights, Armstrong moved to Pittsburgh to pursue a professional career. Armstrong engaged in 62 amateur bouts, 58 of which he won before turning pro. He began his professional career on July 28, 1931, in a fight with Al Iovino, in which Armstrong was knocked out in three rounds.

His first win came later that year, beating Sammy Burns by a decision in six. However, he decided to return to St. Louis. After winning his second pro fight by decision, he moved to Los Angeles with Harry Armstrong. Once in Los Angeles, he decided to return to the amateur ranks. However, since he already had two professional fights under the name Jackson, he told people that he was Harry's little brother, Henry Armstrong. Henry met fight manager Tom Cox at a local gym and secured a contract with Cox for three dollars.

With Cox, he had almost 100 amateur fights, in which he won more than half by knockout and lost none. Standing five feet five and one half inches tall, Armstrong fought in the featherweight class. In 1936, Armstrong split his time among Los Angeles, Mexico City and St. Louis. A few notable opponents of that year include Ritchie Fontaine, Baby Arizmendi, former world champion Juan Zurita, and Mike Belloise. Armstrong knocked out Petey Sarron in six rounds in 1937 to win the World Featherweight Championship.

In 1938, Armstrong defeated Barney Ross by a fifteen-round unanimous decision to win the World Welterweight Championship. Then he defeated Lou Ambers by a fifteen-round split decision to win the World Lightweight Championship. Armstrong was the only boxer to hold world titles in three different weight divisions simultaneously, and all three titles were undisputed championships. He became known for his whirlwind combination of constant movement and knockout punches, earning him numerous new nicknames, including Homicide Hank, Perpetual Motion, and Hurricane Henry.

Armstrong’s feat of holding three titles simultaneously can never be equaled since holding multiple boxing titles was barred in the 1940s. In 1938, Armstrong started with seven knockouts in a row, including one over future world champion Chalky Wright. Armstrong never defended his featherweight crown and forfeited it later in 1938. Ambers beat him in a 15-round return bout for the lightweight championship on Aug. 22, 1939. Still, he had the welterweight crown. And there was money to make by taking it on the road and defending it.

Returning to the welterweight division, Armstrong successfully defended the title five more times, until Fritzie Zivic beat him to take the world title in a 15-round decision. This ended Armstrong's reign as Welterweight Champion. Armstrong's eighteen successful title defenses were the most in history in the Welterweight division. When a rematch three months later saw Armstrong halted in 12, it was clear his world title days were over.

On March 1, 1940, he fought for an unprecedented fourth title in the middleweight division, but lost to Ceferina Garcia in a controversial decision. Most folk thought Armstrong won that fight. Overall, Henry Armstrong faced 17 champions during his career and defeated 15 of them. He holds the record for Welterweight title defenses – making an incredible 19-defenses within a two year span! In 1945, Armstrong retired from boxing. Armstrong’s career span lasted 14 years (1931-1945).

His official record was 152 wins, 21 losses and 9 draws, with 101 knockout wins. He was posthumously inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in the inaugural class of 1990. Armstrong, who was 5-foot-6, varied in fighting weight from 124 to 146 pounds. In 1949 Armstrong experienced a religious conversion and turned his life around. Two years later he was ordained as a Baptist minister at Morning Star Baptist Church. His preaching drew significant crowds to revivals and other meetings.

● Armstrong first won the FEATHERWEIGHT (126-pound) title by knocking out Petey Sarron in six rounds on October 29, 1937.

● On May 31, 1938, he took the WELTERWEIGHT (147-pound) championship from Barney Ross by decision

● On August 17 of that year, he defeated Lou Ambers by a decision to win the LIGHTWEIGHT (135-pound) title.

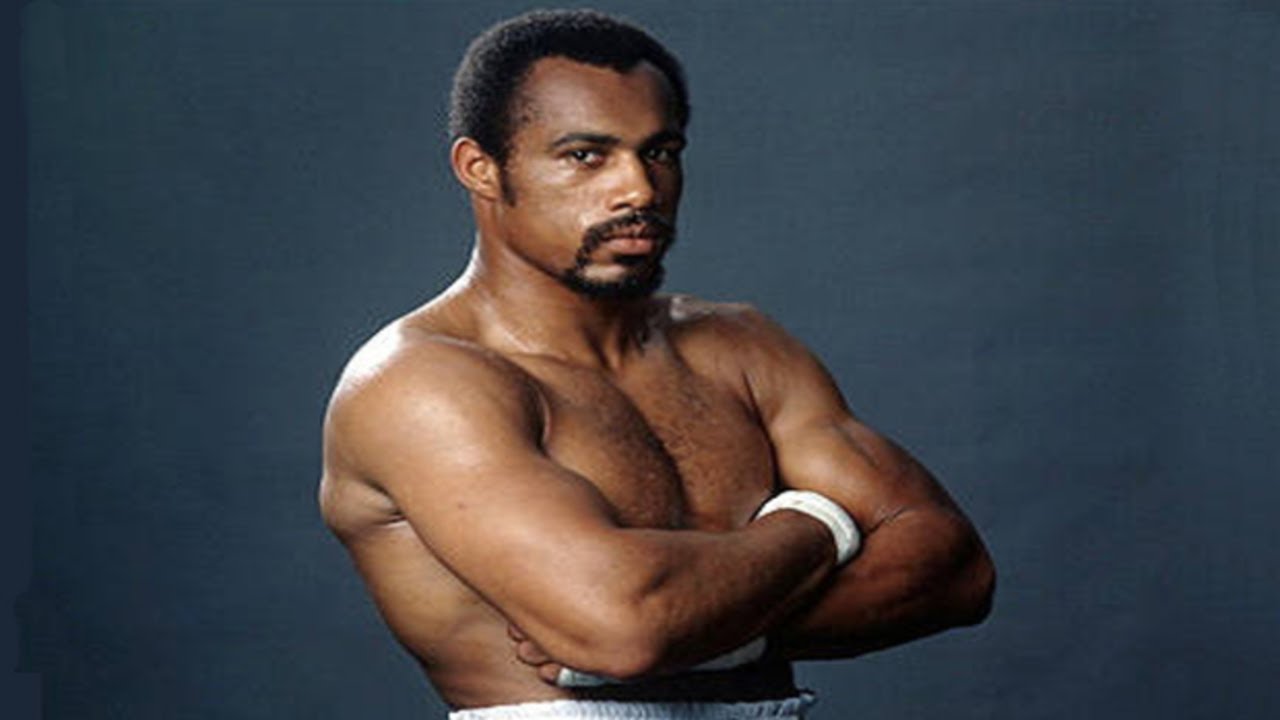

Joe Frazier

Golden Gloves champion, 1964 Olympic Gold Medalist and undisputed World Heavyweight Champion Joe Frazier was born on January 12, 1944 in Beaufort, South Carolina. He dropped out of school when he was 13 years old and went to work. At 15, he boarded a Greyhound bus and went to New York to live with his brother. Joe soon moved to Philadelphia and got a job in a slaughterhouse, where he practiced his punches on sides of meat. He went to a gym to work himself into shape. Shortly after, he began fighting competitively, and began to pursue his boxing dreams.

Joe's boxing potential was noticed by Yancey 'Yank' Durham at the Police Athletic League in Philadelphia. Joe won the novice heavyweight title at the Philadelphia Golden Gloves tournament. He also won the Middle Atlantic Golden Gloves heavyweight championship for three consecutive years. In 1964, hoping to make the 1964 U.S. Olympic team, he lost to Buster Mathis in the finals of the Olympic Trials. But Joe got a break. He was subsequently named the heavyweight representative when Mathis injured his hand.

Joe defeated German Hans Huber, eight years his senior with a 3–2 decision. At 20 years old, Joe won the USA an Olympic gold at the Olympics in Tokyo, Japan with a broken left thumb. He was the first American to win gold in the heavyweight division. After the Olympics, Joe Frazier made his professional debut on August 16, 1965 against Woody Goss and won with a first-round knockout. A year before Frazier’s pro debut, Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) won the heavyweight championship in a huge upset of Sonny Liston.

In 1966, as Frazier's career was taking off, Durham contacted Los Angeles trainer Eddie Futch. Futch had a reputation as one of the most respected trainers in boxing. Under Futch's tutelage, Frazier adopted the bob-and-weave defensive style by making him more difficult for taller opponents to punch and giving Frazier more power with his own punches.

During Frazier’s amateur career he was one of the best heavyweights in the United States. He won his first 11 bouts by knockouts, before a tough night came in the form of the unmovable Oscar Bonavena. In September 1966 and somewhat green, Frazier won a close decision over rugged contender, despite Bonavena flooring him twice in the second round. A third knockdown in that round would have ended the fight under the three knockdown rule. Frazier rallied and won a decision after 12 rounds.

After Bonavena, Frazier knocked out contenders Doug Jones (KO 5), George Chuvalo (TKO 4) and closed out the '67 campaign with a 19-0 career record. By February 1967, Joe had scored 14 wins and his star was beginning to rise. This culminated with his first appearance on the cover of Ring Magazine. After Muhammad Ali was stripped of his heavyweight title in 1967, the heavyweight championship became muddled. To fill the vacancy, the New York State Athletic Commission held a bout between Frazier and Buster Mathis.

After going undefeated in his first 20 bouts, Frazier finally got a shot for the New York heavyweight title on March 4, 1968. The winner to be recognized as "World Champion" by New York State. A relentless Frazier wore down the bigger, heavier man, and stopped Mathis in the 11th round. He closed 1968 by again beating Oscar Bonavena via a 15-round decision in a hard-fought rematch. By winter 1968, his record was 21-0.

By 1970 Smokin Joe had been boxing for 5 years. He was Nicknamed “Smokin’ Joe” by his manager Durham (“Come on, make that bag smoke,” Yank would yell at his charge as he went to work on the heavy bag). On February 16, 1970, Frazier faced WBA Champion Jimmy Ellis at Madison Square Garden for the heavyweight championship. Frazier won by a technical knockout, when he knocked out Jimmy Ellis in five rounds and became the heavyweight champion.

In his first title defense, Frazier traveled to Detroit to fight World Light Heavyweight Champion Bob Foster. In fall of 1970, Ali knocked out top contenders Jerry Quarry and Bonavena, setting the stage for the most anticipated heavyweight title fight since the Louis-Conn rematch of 1946. On March 8, 1971, at Madison Square Garden, Frazier and Muhammad Ali met in the first of their three bouts which was called the "Fight of the Century. Ali had been stripped of the heavyweight title in the spring of 1967 for refusing to enter the U.S. Army.

Frazier won a 15-round unanimous decision 9–6, 11–4, 8–6–1 and claimed the lineal title. Two years later, Frazier lost his title to George Foreman on January 22, 1973, in Kingston, Jamaica. Foreman knocked him down six times before the fight was stopped in the 2nd round. Ali subsequently upset Foreman to recapture the heavyweight title. He and Frazier were matched to fight in Madison Square Garden for a second time on January 28, 1974. In contrast to their previous meeting, the bout was a non-title fight, with Ali winning a 12-round unanimous decision.

Ali and Frazier met for the third and final time in the "Thrilla in Manila", on October 1, 1975. After 14 grueling rounds, Ali returned to his corner demanding they cut his gloves and end the bout. However, Ali's trainer, Angelo Dundee ignored Ali. This proved fortuitous, as across the ring, Fraizer's trainer, Eddie Futch stopped the fight out of concern for his fighter. Frazier had a closed left eye, an almost-closed right eye, and a cut. Ali later said that it was the "closest thing to dying that I know of."

In 1976, Frazier (32–3) fought George Foreman for a second time. After a second knockdown, the fight was stopped in the fifth round. Shortly after the fight, Frazier announced his retirement. He retired again after a draw over 10 rounds with hulking Floyd "Jumbo" Cummings in 1981. Joe Frazier hung up his boxing gloves and retired from boxing with a 32-4-1 record with 27 knockouts. In 1990, Frazier was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. No other heavyweight is as respected and is as admired as a hard worker than Joe Frazier. He is considered one of the best heavyweights of all-time, a true champion. His enduring legacy is ensured.

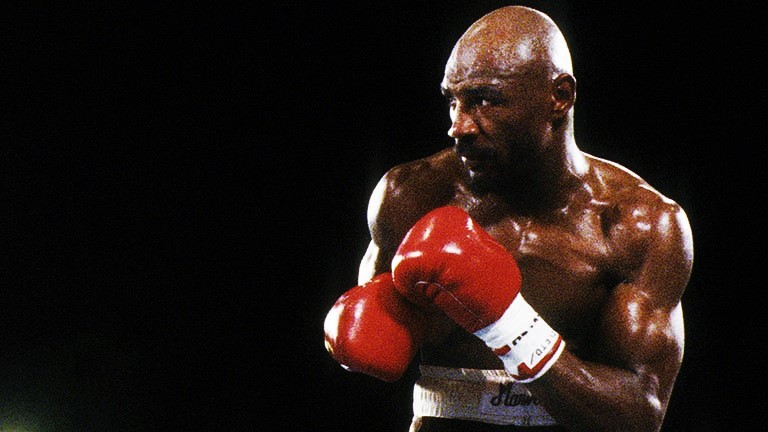

Marvelous Marvin Hagler

One of the most formidable boxers of his era, Marvelous Marvin Hagler defended his title 12 times before losing to Sugar Ray Leonard in a 1987 split decision. Marvin Nathaniel Hagler was born in Newark, New Jersey, one of six children. After the Newark riots of the late 1960s, his family moved to Brockton, MA., the hometown of the heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano. Lacking money for a boxing gym growing up, a teenaged Hagler often shadowboxed on apartment rooftops. would pretend he was Floyd Patterson or Emile Griffith.

He was discovered as an amateur by the Petronelli brothers, Goody and Pat, who ran a gym in Brockton and would go on to train Hagler for his entire pro career. Hagler began his boxing career, winning 57 amateur fights and the 1973 Amateur Athletic Union middleweight title before turning professional. He struggled to find high-profile opponents willing to face him in his early years. After losing two matches in 1976 to middleweights Bobby Watts and Willie Monroe, Hagler remained unbeaten for another decade.

Hagler maintained he had been robbed and went on to win a rematch and then knock Monroe out in a third meeting. Hagler said Frazier had told him: “You have three strikes against you: you’re black, you’re southpaw and you’re good.” The rugged middleweight fought the toughest middleweights in the world for years before he was given the opportunity to fight for a world title. Hagler was finally given a title shot by champion Vito Antuofermo in 1979 but the two combatants fought to a draw.

As the champion, Antuofermo retained his crown. Vito Antuofermo later lost his title to British boxer Alan Minter. His next chance came the following year against Britain’s Alan Minter at Wembley. A hostile atmosphere had been stoked by Minter, by then the champion, saying he would "never lose his title to a Black man." Hagler took the world middleweight title from Alan Minter with a third-round knockout on September 27, 1980.

But after gaining the title Hagler got his revenge, defeating Antuofermo on a fifth-round technical knockout in 1981. Hagler acquired the nickname "Marvelous" when he fought as an amateur in Massachusetts and preened in the ring, emulating Muhammad Ali. He got annoyed when network announcers did not refer to him as such. So he legally change from Marvin Nathaniel Hagler to Marvelous Marvin Hagler in 1982.

A fight against Roberto Durán followed on November 10, 1983. Durán was the WBA light middleweight champion and went up in weight to challenge for Hagler's middleweight crown. Hagler, with his left eye swollen and cut, came on strong in the last two rounds to win the fight. Hagler won a unanimous 15-round decision. Durán was the first challenger to last the distance with Hagler in a world-championship bout.

In April 1985, in one of Hagler’s finest bouts, he pummeled Thomas Hearns, dispatching him in three rounds. They traded punches for three minutes in an opening round many consider the best in boxing history. Though brief, the Hagler-Hearns fight is regarded by boxing historians as one of the most ferocious and compelling bouts in the sport’s history. The entire fight lasted eight minutes. It will be remembered for an eternity. Hagler wanted to retire after beating Hearns.

Hagler was unmistakable in the ring, fighting out of a southpaw stance with his bald head glistening in the lights. He was relentless and he was vicious, stopping opponent after opponent. Hagler fought on boxing’s biggest stages against its biggest names. A member of the famed "Four Kings" of the 1980s, a celebrated group of Hall of Fame middleweights that included Hearns, Leonard and Roberto Duran. All four men etched their primes battling at welterweight and middleweight during the late 70s and 80s boxing glory years.

Bob Arum, Hagler’s longtime promoter, convinced Hagler to defend his title again. Hagler would fight only two more times, after the Hearns fight. The first one was stopping John Mugabi a year later. Sugar Ray Leonard, who had been retired for two years, watched the fight from ringside. Leonard wanted to fight Hagler. Years earlier, after losing to Hagler, Duran told Leonard he had the skills to outbox him. Marvelous Marvin wanted nothing to do with him. The bitterness Hagler felt for Leonard ran deep.

When Sugar Ray Leonard emerged from a brief retirement in 1987, their were demands for a superfight with Hagler. Hagler defended his title against Sugar Ray Leonard who was coming off a three-year layoff from a detached retina, in his final fight in 1987. Hagler entered the match as the heavy favorite, having not lost a bout in more than a decade. But Leonard won in a controversial 12-round split decision. Unable to accept the defeat, Hagler retired from boxing at age 32 with 62 career wins (52 KOs) against just 3 losses.

Leonard was willing to do it again. “He deserved a rematch,” Leonard said. Hagler wanted no part of it. By then, Hagler had settled down into a new life as an actor in Italy and was now uninterested in his past boxing life. Hagler never once seriously considered a rematch. He reigned as the undisputed champion of the middleweight division from 1980 to 1987, making twelve successful title defenses, all but one by knockout. Quiet with a brooding public persona, Marvelous Marvin Hagler competed in boxing from 1973 to 1987.

He moved to Italy and became immersed in the Italian film scene, appearing in several action movies. Deservedly inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1993 as arguably the best defensive-minded southpaw ever, he left an enduring legacy still revered by historians and fans alike. At his crushing best, outsmarting dangerous punchers, Hagler embodied the consummate middleweight champion conquering every challenge the golden middleweight era posed.

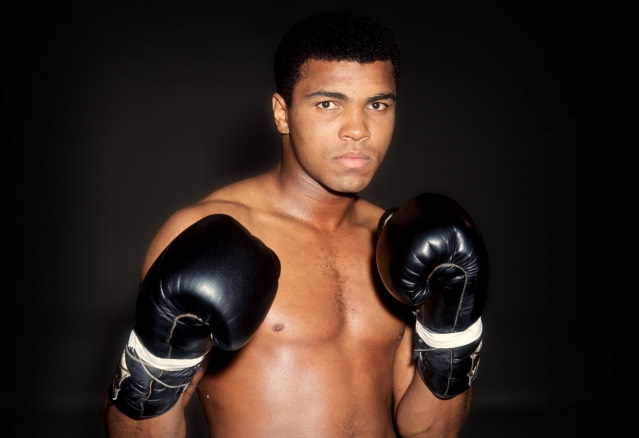

Muhammad Ali

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., aka Muhammad Ali the first fighter to win the world heavyweight championship on three separate occasions, was born January 17th 1942 in Louisville, Kentucky. At Central High, Cassius’s marks were so bad in the tenth grade that he had to withdraw and then come back and repeat the year. A career in professional football or basketball seemed to require college, and that, he felt, wasn’t going to happen. Boxing was the path. He daydreamed in class, shadowboxed in the hallways.

He trained at first in the gym of a local police officer named Joe Martin. In his first amateur bout in 1954, he won the fight by split decision. Clay went on to win the 1956 Golden Gloves tournament for novices in the light heavyweight class. Three years later, he won the National Golden Gloves Tournament of Champions, as well as the Amateur Athletic Union’s national title for the light heavyweight division. As Cassius Clay, Ali travelled to the 1960 Rome Games to compete in the light heavyweight division.

Despite being only 18, he won all four of his fights easily. Clay won the gold medal with a victory over a lumbering opponent from Poland. After his Olympic victory, Clay was heralded as an American hero. As his profile rose, Ali acted out against American racism. After he was refused services at a soda fountain counter, he said, he threw his Olympic gold medal into a river.

He soon turned professional with the backing of the Louisville Sponsoring Group and continued overwhelming all opponents in the ring. Next, he began a professional career under the guidance of the Louisville Sponsoring Group. Clay won his professional boxing debut on October 29, 1960, in a six-round decision.

From the start of his pro career, the 6-foot-3-inch heavyweight overwhelmed his opponents with a combination of quick, powerful jabs and foot speed. His constant braggadocio and self-promotion earned him the nickname “Louisville Lip.” After winning his first 19 fights, including 15 knockouts, Clay received his first title shot on February 25, 1964, against reigning heavyweight champion Sonny Liston. Although he arrived in Miami Beach, Florida, a 7-1 underdog, the 22-year-old Clay relentlessly taunted Liston before the fight.

Clay promised to “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” and predicting a knockout. When Liston failed to answer the bell at the start of the seventh round, Clay was indeed crowned heavyweight champion of the world. “I’m King of the World!” he shouted to the reporters at ringside. The next morning at his press conference Ali converted to the religion of Islam. He first changed his name from Cassius Clay to Cassius X, but later changed it to Muhammad Ali- bestowed by Nation of Islam founder Elijah Muhammad. Ali solidified his hold on the heavyweight championship by knocking out Liston in the first round of their rematch on May 25, 1965 in Lewiston, Maine. He successfully defended his title eight more times.

On April 28, 1967, Ali made his refusal to join the armed forces formal, claiming conscientious objector status. That same day, the New York State Athletic Commission withdrew his boxing license and stripped him of his title. Boxing commissions across the country refused to allow him to fight in their jurisdictions, effectively banishing Ali from the sport. Convicted of draft evasion, Ali was sentenced to the maximum of five years in prison and a $10,000 fine, but he remained free while the conviction was appealed.

Because he refused to join the army, the boxing association didn't allow him to fight for three years starting in 1967. He continued training, formed amateur boxing leagues, and fought whomever he could in local gyms. In 1970 the New York State Supreme Court ordered his boxing license reinstated. Ali returned to the ring on October 26, 1970, and knocked out Jerry Quarry in the third round at Atlanta’s City Auditorium. The following year the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his conviction in a unanimous decision.

On March 8, 1971, Ali got his chance to regain his heavyweight crown against reigning champ Joe Frazier in what was billed as the “Fight of the Century.” The undefeated Frazier floored Ali with a hard left hook in the final round and won an unanimous decision. It was Ali's first defeat as a pro. After suffering a loss to Ken Norton, Ali beat Frazier in a rematch on January 28, 1974. After the unanimous decision over Frazier in that non-title rematch Ali was granted a title shot against 25-year-old champion George Foreman.

The October 30, 1974, fight in Kinshasa, Zaire, was dubbed the “Rumble in the Jungle.” Ali won in an eighth-round knockout to regain the title stripped from him seven years prior. Ali successfully defended his title in 10 fights, including the memorable “Thrilla in Manila” on October 1, 1975. His bitter rival Frazier, his eyes swollen shut, was unable to answer the bell for the final round. Ali later said that it was the "closest thing to dying that I know of."

Ali announced his retirement in 1981 after two unsuccessful bids for a fourth world title, against Larry Holmes and Trevor Berbick. He was always a colorful and controversial character, in and out of the ring. His habit of nominating the round in which he intended to beat his opponent added to the appeal of this innate showman. During his retirement, Ali devoted much of his time to philanthropy and humanitarian affairs. In 1996, Ali was chosen to light the flame during the Opening Ceremony of the Atlanta Olympic Games.

In 1998 Ali was honored with the United Nations Messenger of Peace award. His brazen outspokenness and unsurpassed boxing skills made him a heroic symbol of black masculinity to Black Americans across the country, yet at times he seemed to take pride in humiliating his Black opponents. At the peak of his ability, he bravely sacrificed his career by refusing to go to war in Vietnam – and though he was condemned for it, Muhammad Ali would later be celebrated as a principled pacifist.

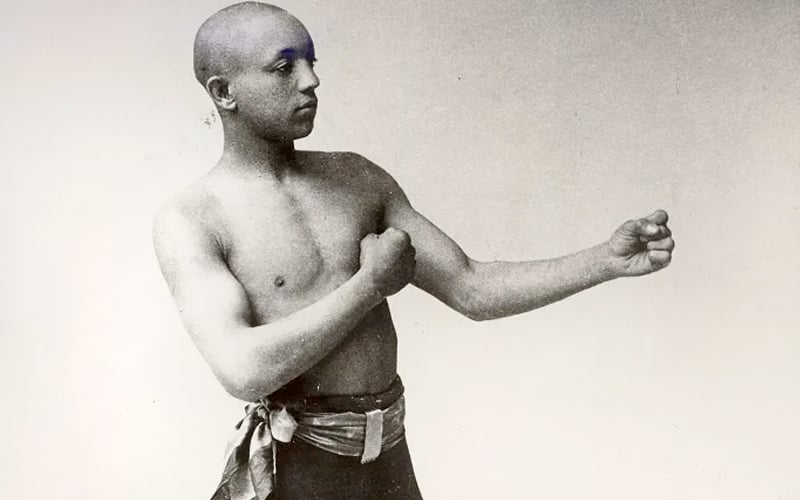

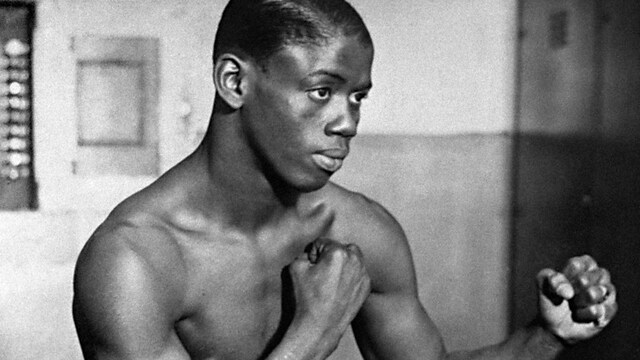

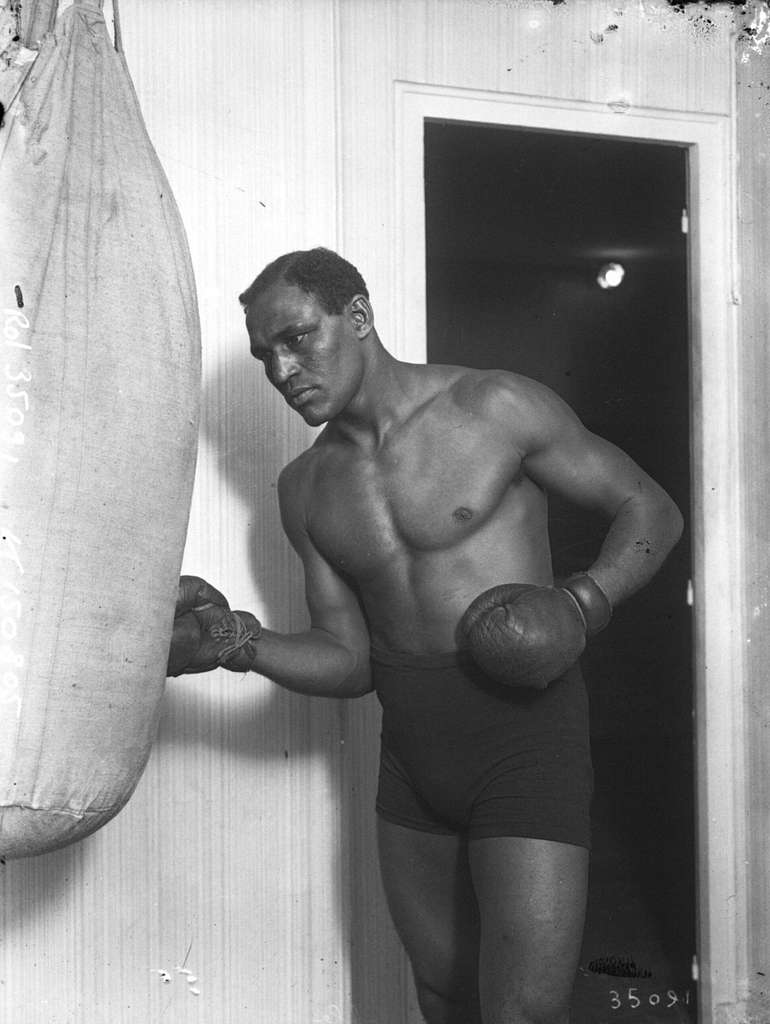

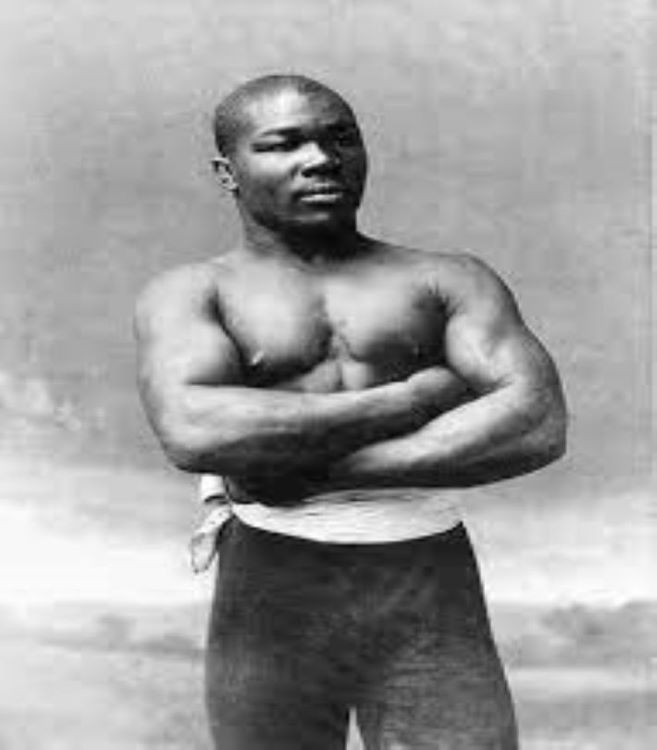

Tom Molineaux

Regarded as America’s first great prizefighter, very little is known about Molineaux’s early life. Bare-kunckle boxer Tom Molineaux, was born in 1784 to parents enslaved by a wealthy Virginian plantation owner named Molineaux. He boxed with other slaves to entertain plantation owners. Molineaux earned his owner a large sum of money in winnings on bets, and was granted his freedom. Around 1804, he traveled to New York City, where he was said to have been involved in “several battles”.

He soon earned the title of “Champion of America.” After a few successfull fights, Molineaux left for England and began boxing there. He spent much of his career in Great Britain and Ireland, where he had some notable successes, and was able to earn money as a professional boxer. Molineaux was trained by Bill Richmond, another freed American slave who became a notable prize fighter in England. Richmond had been in England since 1777. The duo was a perfect fit. With Richmond’s help, Molineaux began to vanquish his opponents fight after fight after fight.

Molineaux’s first fight in England was on 24 July 1810, beating Jack Burrows in 65 minutes. Molineaux’s second fight in England was against Tom Blake whose nickname was “Tom Tough”. Molineaux was victorious after 8 rounds when Blake was knocked out by Molineaux. The ease with which he won quickly lined him up for a title shot against British heavyweight champion Tom Cribb.

In December of 1810, Molineaux challenged Tom Cribb, widely viewed as the Champion of England, in a classic encounter. Tom Cribb was a legend in the annals of bare-knuckle boxing. He routinely drew tens of thousands of spectators to his matches. He was also incredibly tough. Cribb was champ from 1809 thru 1822 and retired with only one loss, that in his first year as a professional fighter.

Molineaux fought Tom Cribb at Shenington Hollow in Oxfordshire for the English title. Long before the first punch was thrown, the pro-Cribb crowd began hurling racist invectives at the Black American fighter. Molineaux seemed undeterred. Round after round, he knocked the English champion down. After the 34 rounds Molineaux said he could not continue but his corner persuaded him to return to the ring. After some 39 rounds of give and take, Molineaux finally collapsed from exhaustion.

The rematch, on September 28, 1811, was equally as exciting and was watched by 15,000 people. Cribb broke his jaw and finally knocked him out in the 11th round. The two Crib fights had made Molineaux a celebrity in England. History had already been made. The first match had secured Molineaux a hallowed place as one of the sport’s top athletes. Molineaux fought 4 subsequent bouts, winning three and losing one. Molineaux’s prizefighting career ended in 1815. However he continued to show his talents in sparring exhibitions. After his visit to Scotland, he toured Ireland and boxed in exhibitions.

“Sugar Ray” Leonard

“Sugar Ray” Leonard is a boxing icon, Olympic gold medalist and world title holder in five weight divisions. Leonard was born Wilmington, Washington, D.C., and Palmer, Md., a racially mixed lower-middle class suburb of Baltimore, on May 17, 1956 as Ray Charles Leonard. The family first moved to Washington and then to Palmer when Ray was ten. Ray was ‘goaded’ into boxing by his brother Roger, who started boxing as a teenager. At the age of thirteen, Ray started training with Dave Jacobs and Ollie Dunlap at the Palmer Park Recreation Center.

By the age of fifteen, Ray started competing in amateur matches, eventually winning the 1973 National Golden Gloves Lightweight Championship. The following year, he won the Golden Gloves title again, along with the National AAU Lightweight Championship. Sugar Ray ended his amateur career with a fabulous 145-5 record. In 1976, Ray represented the United States Olympic Boxing team. Leonard won the Olympic Boxing Gold Medal after defeating Andrés Aldama, in a 5-0 decision, in the light welterweight category.

At the time, he says, he had no intention of going professional. "This is my last fight," Leonard said. "My decision is final. My journey is ended, my dream fulfilled." But Leonard soon changed his mind when his family needed money. Ray hired attorney Mike Trainer as his business manager. Trainer got him proper training and management with Angelo Dundee, who trained Muhammad Ali. Leonard won his first professional fight with a six-round unanimous decision over journeyman Luis Vega in February 1977.

Leonard continued to move through the ranks by impressively beating the likes of perennial contenders. By his thirteenth professional fight, Ray fought his first world ranked opponent Floyd Mayweather. In 1979, he defeated Mayweather for the NABF Welterweight Championship. He also won the WBC welterweight title in 1979 after stopping Puerto Rican phenom Wilfred Benitez in November 1979. This was a violent chess match that pitted two of the game's master technicians.

Leonard held the title for less than seven months. In 1980, Leonard faced legendary lightweight champion Roberto Duran in what may be the most anticipated non-heavyweight fight in history. In a fast-paced battle, Duran dethroned Leonard with a unanimous 15-round decision. It was his first professional defeat, but it again emphasized that he had incredible substance behind his considerable skill set.

The direct rematch was further testament, as Leonard completely rethought his approach. On Nov. 25, 1980, in New Orleans, Leonard boxed Duran, who had a 72-1 record, into submission. Leonard regained the title when Duran quit in the eighth-round of their rematch. Even though the fight was close, Leonard annoyed Duran who said “No Mas” or “No More” in Spanish and called it a night.

On June 25, 1981, Leonard won his second title when he knocked out WBA junior middleweight champ Ayub Kalule in the ninth round. He then returned to the welterweight division for a unification showdown with WBA champ Thomas Hearns. In their 1981 Fight of the Year, Ray inflicted the first career defeat on Thomas ‘Hitman’ Hearns. Leonard and Hearns waged a memorable war. The WBC welterweight champ, "Hit Man" took over in the middle rounds and practically closed Leonard's left eye.

But Leonard, behind on all three scorecards, registered a knockdown in the 13th round and ended the brutal war in the 14th, winning on a TKO. After he defeated Hearns, Leonard had one more fight. He took out Bruce Finch in three rounds and was due to face Roger Stafford, but his plans were derailed by a partially detached retina in his left eye. In May 1982, Leonard underwent an operation for a detached retina and six months later announced his retirement.

After a 27-month absence he returned to the ring in 1984 and knocked out Kevin Howard only to retire again. After nearly three years of inactivity, Leonard returned again and pulled off the Upset of the Decade when he outpointed Marvin Hagler, the long-reigning middleweight king in April 1987, to win the middleweight title in 1987. It was the first time Hagler had lost in 11 years. In November 1988, he came out of retirement to fight again. At 167 pounds, he registered a ninth-round TKO over Don Lalonde to gain the WBC super-middleweight and lightweight titles.

In 1989 Leonard fought a controversial draw in a rematch against Hearns, in which "Hit Man" scored two knockdowns. Leoanrd won a unanimous decision in a third fight against Durán. Leonard was part of the “Four Kings”, a group of boxers who all fought each other throughout the 1980s, consisting of Leonard, Roberto Durán, Thomas Hearns, and Marvin Hagler. At age 34, he challenged WBC super welterweight champion Terry Norris in 1991. He was dropped twice and lost by unanimous decision at Madison Square Garden.

Leonard announced his retirement in the ring immediately after the Norris fight. But in March 1997, he launched another unsuccessful comeback. At 40 he returned to the ring. Hector "Macho" Camacho embarrassed him and registered a fifth-round TKO. It was the first time Leonard had ever been stopped. He ended his professional career with 36 wins, 3 losses, and 1 draw; 2 of his losses came after his first retirement. Ray Leonard legacy as one of the sport's greatest exponents means that his place in boxing history is forever secure.

Sugar Ray Leonard was known for his agility and finesse. He would become the first boxer in the annals of the sport to amass $100 million in purses due to his considerable marketability. At his peak Leonard was a very talented fighter with fast hands, great balance and movement. His strong jab made openings for the overhand right and left hook. Despite his ability he was never afraid to mix it up with tough guys either.

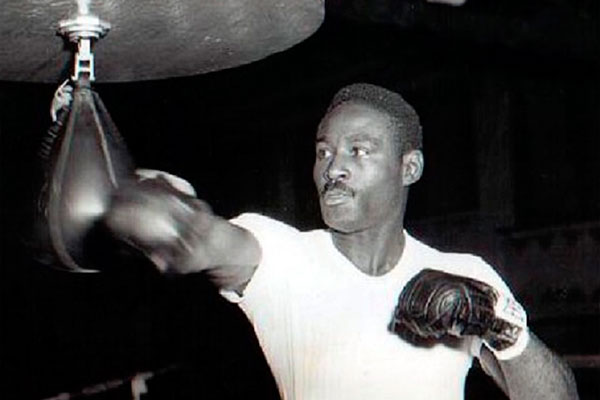

Joe Gans

Born Joseph Gaines in Baltimore in 1874, Joe Gans worked at the city’s waterfront, shucking oysters to help support his family. He did some fighting in Baltimore and that propelled him into a career in the ring. His earliest boxing experience was in a “battle royal” where several boxers were thrown into the ring together and the last one standing got the money. Weighing less than 137 pounds, Gans started boxing professionally in early 1891 in his home town. Joe Gans was the first African American to become a world boxing champion.

As a Black champion reigning during the Jim Crow era, he endured physical assaults, a stolen title, bankruptcy, and numerous attempts to destroy his reputation. Gans stepped into the boxing ring for the first time on October 23, 1893, and fought against Buck Myers, which ended in a no-decision. The Maryland born boxer had incredible speed and athleticism in his fighting style, which helped him to find his feet quickly and deliver accurate punches. He was able to use his unbeatable defense to protect himself from blows and then launch deadly counter-attacks to defeat his adversaries.

Gaining many fans within the boxing world, both White and Black alike, Gans created a “scientific” approach to fighting. His strategy was to learn his opponent’s strengths and weaknesses in order to compete with a game plan. He became known as a true student of the sport, earning him the nickname “Old Master.” His most significant accomplishment was his lightweight championship. By the time he was 26 he had earned a world lightweight title chance against Frank Erne in New York. He knocked out Erne to capture the world lightweight title on May 12th 1902.

That victory made Joe Gans the first Black man to hold any boxing championship. This did not sit well with many, and racism would in fact define both the rest of Gans’ career and his life. After winning the world lightweight title Gans remained champion for six years. One of Gans’ most notable bouts happened in September 1900, against Eddie Connolly, where he won after 10 rounds by KO. From the beginning, what set Joe apart was his intelligence and the sophistication of his ring technique.

Gans developed a style which capitalized on his exceptional athleticism and quickness. Because he was Black, he was compelled by boxing promoters to permit less-talented White fighters to last the scheduled number of rounds with him and occasionally to defeat him. On many occasions, even when he was the victor, he often watched his White opponents walk away with the lion’s share of the cash.

His last professional fight was against Jabez White on March 12, 1909, at the age of 34, Gans won it after 10 rounds in a non-title bout. Joe Gans final record, including newspaper decisions, stands at an astonishing 159-12-20, with many, if not most, of the draws and losses being bouts he actually won or intentionally forfeited. During his storied career, Gans was one of the first to fight with gloves marking the transition from the era of bare-knuckle fights to the modern era. For eighteen years Gans fought in three divisions: featherweight, lightweight, and welterweight.

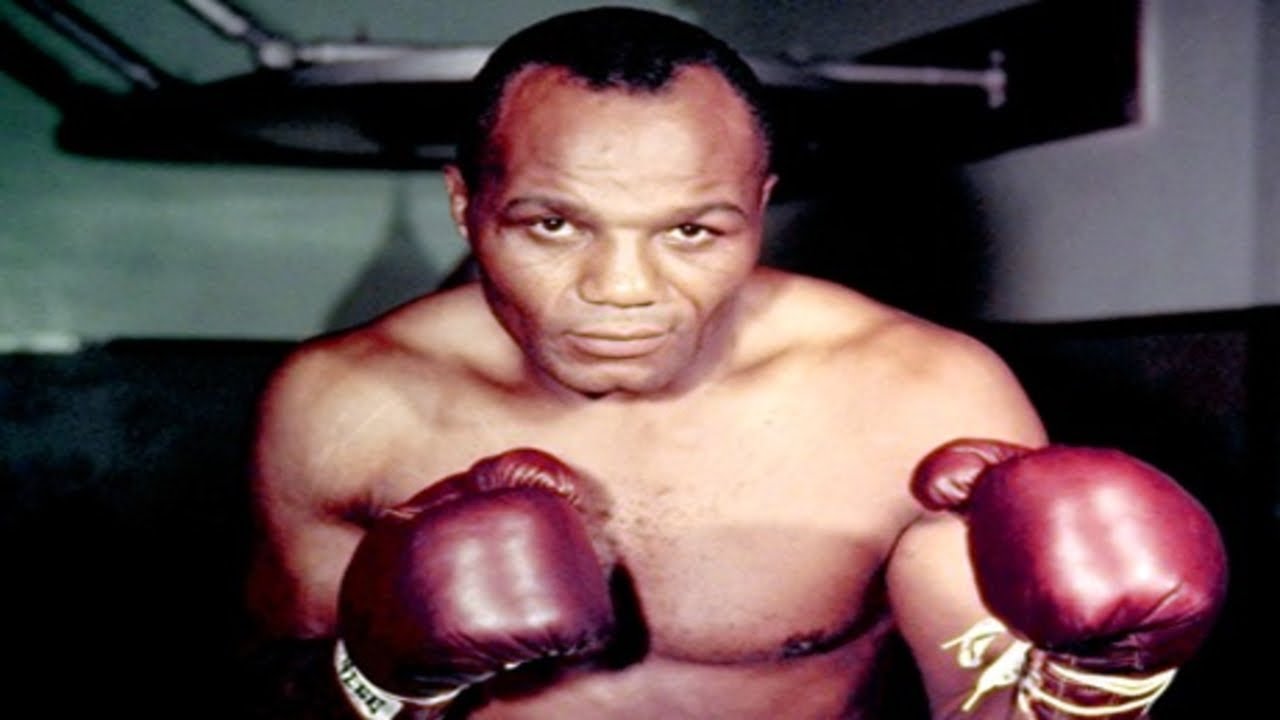

Ezzard Charles

Known as the "Cincinnati Cobra," Ezzard Charles had a career that spanned from 1940 to 1959. Ezzard Charles was born in Lawerenceville, Ga., but grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio. Ezzard moved to Cincinnati at the age of nine to live with his grandmother. It was a chance encounter with Cuban featherweight sensation Kid Chocolate (Eligio Sardiñas), that first made Charles want to be a fighter. The young Ezzard was so impressed with the beautifully tailored suit worn by the famous champion that he decided then and there he wanted to be a prizefighter.

Charles started his career as a featherweight in the amateurs, where he had a record of 42–0. In 1938, he won the Diamond Belt Middleweight Championship. He followed this up in 1939 by winning the Chicago Golden Gloves tournament of champions. He won the national AAU Middleweight Championship in 1939. At the age of 18, Charles turned professional in 1940. Charles put together an impressive string winning all of his first 17 fights before being defeated by veteran Ken Overlin. Nevertheless, Charles had started to solidify himself as a top contender in the middleweight division.

Charles however came back, defeating notable fighters including Teddy Yarosz, Joey Maxim, and Anton Christonfroridis. Ezzard Charles was considered the third leading middleweight in the country, when he was to face the esteemed Charley Burley, in May of 1942. Burley was a prodigious fighter whose dexterous jab and catlike reflexes led opponents into counters all night long.

Burley was famously claimed to be so talented that even world champions were refusing to fight him. Burley was placed in the “”Murderer's Row”, a select group of talented African American fighters whom weren’t given their rightful shots at championships. They found themselves fighting one another or lesser matched opposition than anything else. To the surprise of many, then 20 year-old Charles won a thriller with Burley. A month later, he bested him again.

Before being enlisted into the military before World War II, Charles was beating the likes of future light heavyweight champions such as Joey Maxim ( famously known for his win over Sugar Ray Robinson in summer heat). While serving in the U.S. Army during World War II Charles was unable to fight professionally in 1945. Ezzard wanted to fight again after the war, so he kept himself in shape during the war, by running as much as he could and shadow boxing.

Charles returned to boxing after the war as a light heavyweight. His early bouts were against the top middleweights and light heavyweights in the world. He defeated Archie Moore, Lloyd Marshall, and Jimmy Bivins to earn a number two ranking in the light heavyweight class. He fought a total of five light heavyweight champions, defeating four of them, but never received an opportunity to fight for the division’s title. From 1946 to 1951, Ezzard Charles went on a warpath, carving out a winning streak that saw his legacy as the uncrowned king of light heavyweights set in stone.

Tragedy struck Ezzard Charles when he on February 20, 1948, hefought a young contender named Sam Baroudi. He knocked Baroudi out in Round 10. But the next day, Baroudi died of the injuries he sustained in this bout. Charles was so devastated he almost gave up fighting. A need to provide for his family along with encouragement from Baroudi's family convinced him to continue. Charles was unable to secure a title shot at light heavyweight and moved up to heavyweight. After knocking out Joe Baksi and Johnny Haynes, Ezzard Charles got his chance. After Joe Louis retired from the ring the first time.

Charles fought for the vacant National Boxing Association heavyweight title on June 22, 1949 against “Jersey” Joe Walcott and earned a 15-round decision victory. The next year Louis came out of retirement and Charles defeated him on September 27, 1950, gaining recognition as the undisputed world heavyweight champion. He successfully defended the title three times before losing it to Walcott, by knockout in the seventh round, on July 18, 1951. Charles knocked out Bob Satterfield in an eliminator bout for the right to challenge Heavyweight Champion Rocky Marciano.

His two stirring battles with Marciano are regarded as ring classics. In the first bout, held in Yankee Stadium on June 17, 1954, he valiantly took Marciano the distance, going down on points in a vintage heavyweight bout. Charles is the only man ever to last the full 15-round distance against Marciano, the “Brockton Blockbuster.” In their September rematch, Charles landed a severe blow that actually split Marciano's nose in half. Marciano's cornermen were unable to stop the bleeding and the referee almost halted the contest until Marciano rallied with an eighth-round knockout.

Never had Rocky’s crown been so perilously close to being taken. Marciano, however, stated without hesitation that Charles was the toughest opponent he ever faced during his 49-0 ring career. Ezzard Charles was not as widely celebrated as some other heavyweight champions, partly because he followed in the wake of the immensely popular Joe Louis. However, he earned respect for his durability and technical mastery, qualities that enabled him to beat a range of top fighters in various weight classes, including Archie Moore.

Age and damage sustained during his career caused Charles to begin a sharp decline following his title fights. Overall Charles lost 13 of his final 23 fights. In 1959, Charles retired with a record of 93-25-1 (52 KOs). A clever boxer, over the course of his professional career he defeated many of boxing’s greatest fighters including Charley Burley, Joey Maxim, Archie Moore (three times), “Jersey” Joe Walcott, Gus Lesnevich, and Joe Louis. Ezzard Charles never weighed more than 200 pounds, but he was an outstanding heavyweight champion.

He could seamlessly blend between defence and offense and adapt on the fly. He was subsequently elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990. While Charles' career had its share of losses, his numerous victories and remarkable performances in the ring showed why he was one of the best boxers ever. Ezzard Charles was one of the greatest ring technicians that ever laced on a pair of gloves.

Jersey Joe Walcott

The story of perseverance in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds for Joe Walcott is inspiring. Born Arnold Cream in Merchantville, New Jersey, Joe Walcott quit school and worked in a soup factory to support his mother and 11 younger brothers and sisters after his father had passed away. Arnold Cream also began training as a boxer at age fourteen. He became a good boxer, but not good enough to give up his day job at a soup factory. Arnold took the name of his boxing idol, "Barbados" Joe Walcott, a welterweight champion from Barbados. He also took the name "Jersey" to distinguish himself and show where he was from.

Walcott debuted as a professional middleweight boxer on September 9, 1930, fighting Cowboy Wallace and winning by a knockout in round one. After five straight knockout wins, in 1933, he lost for the first time, beaten on points by Henry Wilson in Philadelphia. Walcott lost early bouts against world-class competition. He lost a pair of fights to Tiger Jack Fox and was knocked out by contender Abe Simon. Abe Simon was the only ranked fighter he fought.

Walcott retired for 4 years after the 1940 Simon KO defeat. Jersey Joe Walcott was not well-know for almost 15 years. But that would change in 1945. From 1944-47 the 30 year old Walcott made a comeback and evolved into a contender for the heavyweight championship. A chance meeting with a fight promoter who recognized the potential in his iron chin and hard punch turned Walcott’s fortunes around, launching one of the greatest comebacks in boxing history.

From 1944-47 the 30 year old Walcott made a comeback and evolved into a contender for the heavyweight championship. Walcott began fighting and beating top heavyweights such as Curtis Sheppard, Joe Baksi and Jimmy Bivins in 1945. In 1946 Walcott narrowly defeated Jimmy Bivins by split decision. He closed out 1946 with a pair of losses to former light heavyweight champ Joey Maxim and heavyweight contender Elmer Ray, but promptly avenged those defeats in 1947. Walcott had built a record of 45 wins, 11 losses and 1 draw before challenging for the world title for the first time.

In the first 17 years of his career Walcott had not established himself as anything more than a longshot fringe contender. The Joe Louis fight however would have one bit of historical significance. In the 55 year history of boxing's gloved era, this fight would be only the second heavyweight championship ever contested between two Black men. This fight would essentially break the color barrier in heavyweight championship boxing. Walcott, considered an excellent boxer and slick defensive fighter, challenged Joe Louis for the title in December of 1947 at Madison Square Garden.

Boxing smoothly, and counter-punching effectively, Walcott befuddled Louis while dropping him twice and building a lead in the scoring. He dropped the champion twice but lost a controversial 15-round split decision to "The Brown Bomber". The best Walcott could hope for was a rematch and on June 25, 1948. Louis defeated him again, knocking Walcott out in 11 rounds. Louis would announce his retirement after this fight. When Louis retired, Jersey Joe was matched with Ezzard Charles to decide the Brown Bomber’s successor.

On June 22, 1949, Walcott was matched with Ezzard Charles for the vacant heavyweight championship. Charles had been a top rated middleweight and light-heavyweight contender before joining the heavyweight ranks. However, Charles prevailed, when he scored a comfortable 15 round unanimous decision win over Walcott. Charles weighed only 6 pounds above the light-heavyweight limit. Walcott beat future Hall of Famer Harold Johnson in 1950 and would win four of his five bouts.

In 1950, Walcott won 5 straight fights against unranked opponents before losing a unanimous decision to contender Rex Lane. Surprisingly, Walcott was granted another title fight with Ezzard Charles. On March 7, 1951 Charles won a lopsided 15 round unanimous decision while dropping Walcott for a 9 count in the 9th round. But in the rematch, Walcott caught lightning in a bottle with a one punch left hook 7th round KO of Charles. After 21 years as a professional fighter, Jersey Joe Walcott was heavyweight champion of the world. At 37 years of age, had become the oldest man to ever win the heavyweight title.

Jersey Joe would meet arch-nemesis Charles, a fourth time, earning a decision in his first title defense. On September 23, 1952, he goes against unbeaten contender Rocky Marciano. This was his second defense and he lost the title when the "Brockton Blockbuster" halted him in Round 13. Marciano landed first and flush on Walcott's jaw with a devastating right hook and a powerful left followup. Walcott collapsed with his left arm hanging over the ropes, slowly sinking to the canvas, where he was counted out. It took several minutes to revive Walcott. The title changed hands in an instant.

Walcott's brief 1 year reign as heavyweight champion was over. There was a rematch on May 15, 1953, in Chicago. The second time around, Marciano retained the belt by a knockout in the first round, when Walcott attempted to become the first man in history to regain the world heavyweight crown. Jersey Joe Walcott had fought his last fight and announced his retirement shortly thereafter. He remained retired for the rest of his life. In his overall career, Walcott had a 51-18-2 record with 32 KO's and was KO'd 5 times.

After retiring, as Arnold Cream, he served as Camden County sheriff in the early 1970s and then spent a decade as the chairman of the New Jersey State Athletic Commission, which oversees boxing in the state. Walcott did not go away from the celebrity scene after boxing. In 1956, he co-starred with Humphrey Bogart and Max Baer in the boxing drama "The Harder They Fall." He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.

Floyd Patterson

He was a light heavyweight-cruiserweight who was good enough to compete with the big boys and actually win the Heavyweight Championship of the World. Floyd Patterson was born in Waco, North Carolina, and was later raised in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn. He was one of eleven children and always into mischief, skipping school and getting caught stealing on several occasions. At age 14 Patterson began working out in a Manhattan, New York gym operated by the noted trainer Gus D’Amato.

In 1950 he began boxing as an amateur he won the National Amateur Middleweight Championship. One year later he captured the New York Golden Gloves middleweight championship. In 1952 he won the Middleweight Championship capturing the gold medal at the Helsinki Olympics. His gold medal was easily won with a first round knockout over Romanian, Vasile Tita. Less than a month after the Olympics, Patterson fought his first professional fight against Eddie Godbold and knocked him out in four rounds.

Patterson's amateur record over 44 fights was 40-4, with 37 knockouts. Patterson grew out of the middleweight class, and was light for a heavyweight at 185 pounds. As an early pro, he fought as a light heavyweight. The first career loss was a controversial decision to former 175-pound champ Joey Maxim. By the time the reigning heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano retired Patterson was a leading heavyweight contender. He was matched to fight Archie Moore for the vacant title on November 30th 1956.

He defeated light-heavyweight champion, Archie Moore, for the vacant heavyweight title. Patterson made history that night, becoming the youngest heavyweight champion in history at that time at 21 years of age. He was also the first Olympic gold medalist to win a heavyweight title. Patterson was an active champion, defending his title four times in succession. Patterson defended the heavyweight title for four years.

In 1959 he lost his title to European champion, Ingemar Johansson. Johansson, was the highest ranked contender. He would become Floyd’s fifth challenger. Johansson was undefeated in 21 fights and had knocked out 13 previous opponents. In a fight that took place at Yankee Stadium on June 26, 1959, Johansson knocked Patterson out in three rounds. The big Swede had knocked Patterson down seven times. Johansson became that country's first world heavyweight champion and the first European to defeat an American for the title since 1933.

The next year on the 20th of June 1960, Floyd Patterson became the first man to regain the heavyweight title when he KO'ed Johansson in the fifth round. A third fight between them was held in 1961, and while Johansson put Patterson on the floor, Patterson retained his title by a knockout in six to win the rubber match. The quality of some of Patterson's opponents as champion was questionable, including 1960 Olympic Champion Pete Rademacher, fighting in his first professional match.

It lead to charges that Patterson was ducking the powerful contender and former convict, Sonny Liston. Patterson, eventually stung by the criticism, agreed to fight Liston while attending an event with President John F. Kennedy at the White House. He lost the title a second time when he was knocked out in the first round of a September 1962 fight against Sonny Liston. Patterson was attempting to become the first boxer ever to win the world's Heavyweight title three times.

Floyd went through a depression after that, often using sunglasses and hats to go out in public and go unnoticed, but he recovered and began winning fights again. He became the number one heavyweight challenger. His attempt to recapture the title from Liston resulted in another first round knockout defeat. This could have been the end, but Patterson, who genuinely loved fighting, with the ring being the place where he expressed himself best, boxed on for almost ten years.

Patterson received two more opportunities to regain the title. He defeated George Chuvalo in a great action fight in February of 1965. In a later comeback attempt, he fought Muhammad Ali, in Las Vegas on November 22 1965, whom newspapers still persisted to call Cassius Clay. In a pre-fight interview, Patterson said, "This fight is a crusade to reclaim the title from the Black Muslims. As a Catholic I am fighting Clay as a patriotic duty. I am going to return the crown to America." Ali toyed with Patterson for nine rounds before winning in a crushing 12th-round defeat.

He then lost a controversial 15-round decision to Jimmy Ellis for the WBA heavyweight title in 1968. Patterson still continued to fight, defeating Oscar Bonavena in ten rounds in 1972. However, a final and decisive defeat to Muhammad Ali in a rematch for the North American Heavyweight title on September 20, 1972 convinced Patterson to retire at the age of 37. Floyd Patterson retired from boxing in 1972 at age 37 with a professional career record of 55 wins, 8 losses, and one draw, with 40 wins by knockout.

He remained active in the sport in retirement, first as a trainer, and eventually as chairman of the New York State Athletic Commission. In retirement, he and Johansson became good friends who flew across the Atlantic to visit each other every year. He also became a member of the International Boxing Hall Of Fame. Although Patterson has often been called one of the least able men to ever hold a boxing title, it should be noted he was a fine gentleman outside of the ring.

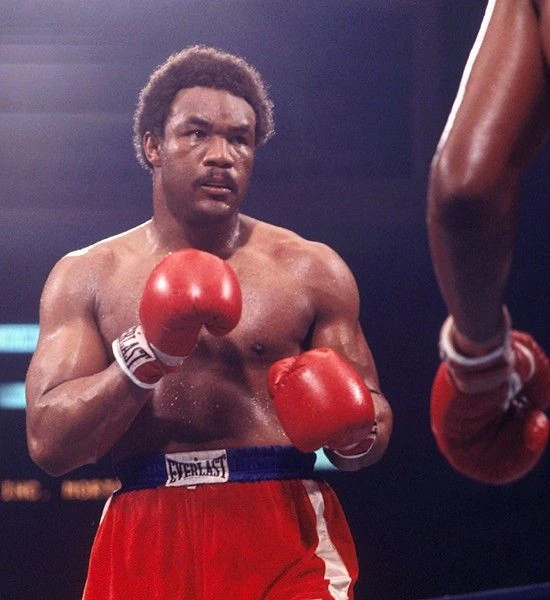

George Foreman

Two-time world heavyweight champion and Olympic gold medalist George Foreman, was born on January 10, 1949, in Houston TX. He eventually dropped out of high school. Football was Foreman’s main sports interest at that point in his life, and a public service television announcement with Jim Brown and Johnny Unitas caught his attention. The two National Football League greats were touting the Job Corps, a new Department of Labor program for so-called troubled youths that Congress had created with passage of the Economic Development Act in 1964.

In August 1965, the Job Corps assigned sixteen-year-old Foreman to the Fort Vannoy Training Center, which operated for about three years near Grants Pass. The starting point for his career as a boxer, Foreman later said, was at Fort Vannoy. One night in November 1965, he listened to a radio broadcast of the bout between Muhammed Ali and Floyd Patterson. One of his job corpsmen asked him about becoming a boxer. Foreman learned to box from Charles “Doc” Broadus, at the Parks Center run by Litton Industries in Pleasanton, California.

He left Fort Vannoy for the Parks Center in February 1966. His amateur fighting record was so good, that he trained and was selected for the 1968 Olympics. At the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, George Foreman won the gold medal in the heavyweight boxing competition. Foreman fought just 20 times as an amateur before traveling to the Mexico City 1968 Olympic Games. He was raw, but strong. “The left jab was my No. 1 punch – I still think it was the best punch in boxing,” Foreman said years later.

In four Olympic bouts, Foreman went the distance just once. He stopped Jonas Cepulis of the Soviet Union in the second round of the gold medal bout, prompting Foreman to dance around the ring carrying a small American flag. Foreman had an amateur record of 22–4, losing twice to Clay Hodges. He also defeated by Max Briggs in his first ever fight. In 1969, Foreman turned professional with a three-round knockout of Donald Walheim in New York. He had a total of 13 fights that year, winning all of them (11 by knockout).

In 1970, Foreman continued his march toward the undisputed heavyweight title, winning all 12 of his bouts. In 1971, Foreman won seven more fights, winning all of them by knockout. After amassing a record of 32–0 (29 KO), Foreman was ranked as the number one challenger by the WBA and WBC. By 1972, Foreman had a perfect 37-0 record which included 35 knockouts. Foreman got his shot at the world heavyweight championship when he fought Joe Frazier on January 22, 1973, in Kingston, Jamaica.

Frazier was the favorite going into the bout. Frazier had won the title from Jimmy Ellis and defended his title four times since, including a 15-round unanimous decision over the previously unbeaten Ali in 1971. Frazier was knocked down six times by Foreman within two rounds, with the three knockdowns rule being waived for this bout. Frazier managed to get to his feet for all six knockdowns, but referee Arthur Mercante eventually called an end to the one-sided bout.

It was the first professional loss for Frazier, the heavyweight gold medalist in the Tokyo 1964 Olympic Games. After becoming the champion, Foreman successfully defended his title twice. He beat Puerto Rican heavyweight champion Jose Roman in only 50 seconds. Foreman also beat Ken Norton, who had just beaten Muhammad Ali, in a mere two rounds. Winning those two fights then set up one of the most famous fights in history: "The Rumble in the Jungle" between Foreman and Muhammad Ali, on October 30, 1974, in Kinshasa, Zaire. Ali knocked out Foreman to regain the heavyweight championship of the world.