Basketball Pioneers

Nat "Sweetwater" Clifton * Chuck Cooper * Earl Lloyd

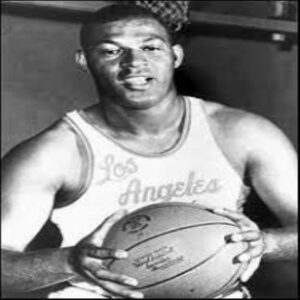

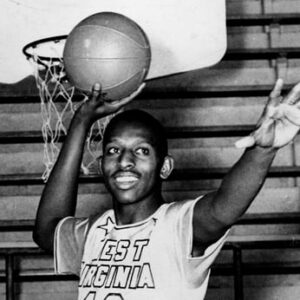

After Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier in professional baseball, the NBA would see three Black basketball pioneers join their league. Chuck Cooper became the first Black player selected in the NBA Draft. Nathaniel “Sweetwater” Clifton became the first Black player to sign an NBA contract and Earl Lloyd became the first Black player to play in an NBA game. This effectively broke the color barrier in the NBA and opened the door for future generations of Black players changing the league and the game of basketball as we know it today.

But the wheels were in motion for Black players to open that door long before Lloyd, Clifton and Cooper made their debuts in the NBA. In fact, the wheels were in motion almost 50 years prior. In 1904, Edwin Bancroft Henderson, a Black Washington, D.C., gym teacher, took a summer course at Harvard and brought the game back to Black segregated schools. From there, it went to YMCAs, and eventually to Black teams with names like the Washington Bears and the New York Renaissance.

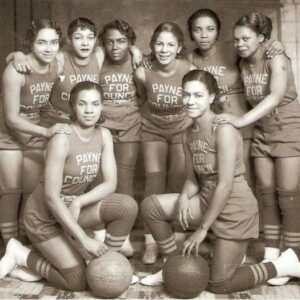

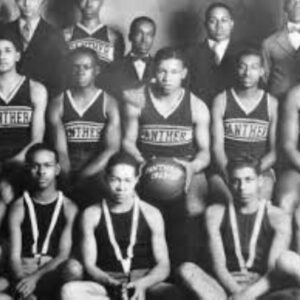

As the game continued to grow in popularity in Black communities, not all of society was prepared for the growth. Segregation kept Black players from integrating with White clubs and Black teams were also prevented from playing in white-owned gymnasiums. In turn, it forced Black teams and players to get creative with where and when to play games. Many turned to church basements, halls, armories and even dance ballrooms. In spite of the roadblocks, Black basketball continued to grow in communities across the country. Black promoters would team up with Black musicians and create dance-basketball events where patrons would be able to attend and dance before and after basketball games.

As such ticket sales began to skyrocket ushering Black basketball into the 1920s. This was the time of the Harlem Renaissance, a period when Black experienced a freedom of expression. When Black music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics, sports, and cultural pride thrived. As games became more organized, Black teams would compete against each other for the “Colored Basketball World’s Champion” moniker. Lester Walton, a sportswriter editor for the New York Age is credited with coining the term. There was no formal championship game or tournament played, the honor was given by consensus of the most prominent Black sportswriters in America who covered basketball.

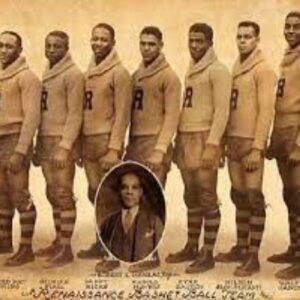

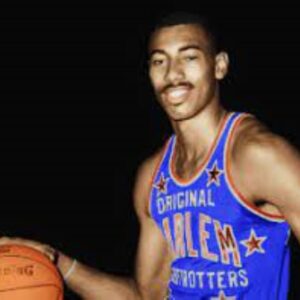

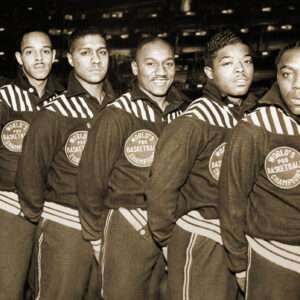

The New York Renaissance, otherwise known as the Harlem Rens, is widely credited with being the most successful team during the era. The Rens were the first all-Black professional team founded and owned by a Black man, Robert Douglass. Because of their on-court dominance, the Rens were invited to the first-ever World Professional Basketball Tournament held in 1938 in Chicago. The tournament featured 10 of the country’s best all-White professional teams and one other all-Black team — the Harlem Globetrotters. The Rens would go on the win the inaugural tournament beating the whites-only basketball league champion Oshkosh All-Stars in the final. The Rens winning on the biggest basketball stage at that time confirmed to many that Black basketball was first-rate in opening the door for integration years down the line in the NBA.

The NBA’s embracing of Black athletes closed the book on the near-50-year history of sustained excellence that was Black basketball. The oft-forgotten era is nicknamed the Black Fives Era. The term “fives” was used in reference to teams starting five players in the early days of basketball which lead to the term ‘Black Fives’ to describe an all-Black team in the early 1900s. The Black Fives Era pioneered basketball.

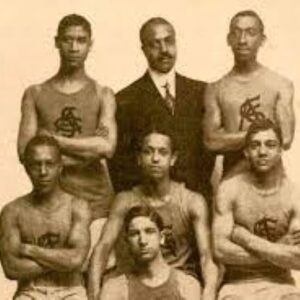

The Rens, were a Black-owned all-Black team based in the Harlem section of New York City during the era of segregated basketball teams, owned by Robert L. Douglas who was a native of the Caribbean island of St. Kitts and a former professional basketball player with the New York Spartans. The team gained their name from their playing location, the Renaissance Casino ballroom in Harlem, New York, where they dazzled fans with their innovative style of play. The Rens were one of the few all-Black, traveling professional basketball teams of that era. Formed five years before the Harlem Globetrotters, the Rens provided Black men with the opportunity to compete against White athletes on an equal footing.

Blacks could compete against each other for “colored” championships and occasionally against Whites when the intent was to stimulate ticket sales by titillating audiences with Black versus White contests. They toured the country competing against Black and White teams, and in the process, compiled one of the most impressive winning streaks in history. But Blacks were never permitted to compete against whites for national championships, which put both more money and White pride at stake. That system kept Black athletes on one side of the divide barnstorming for limited compensation while the White players, on the other side, collected high salaries and big payoffs.

In 1905 in a gym on 10th Avenue, a co-worker introduced Robert Douglas to basketball, the game that became his passion and that he called simply “the greatest thing in the world.” Hooked from the moment of his first exposure, Douglas went on in 1908 to cofound the Spartan Field Club, where Black children could compete in amateur sports, including basketball. Douglas also organized an amateur adult team, the Spartan Braves, for which he starred until he retired as a player at age 36 in 1918 to devote himself full-time to managing the team. Douglas made the transition to professional basketball and changed the name of his team from the Spartan Braves to the Renaissance Big Five.

The Rens were the first Black-owned, full-salaried Black professional basketball team. They often played white teams principally because those “race games” brought consistently large crowds to the casino. In the process, the Rens developed an ongoing rivalry with the best team in professional basketball, the Original Celtics. At first it was not much of a rivalry, because the Celtics, led by Joe Lapchick and Nat Holman, were clearly the better team. However, as the match-ups grew in significance and as the Rens refined their passing game and team defense, they became the only team in all of professional basketball that could claim parity with the Celtics.

Douglas tried to join the highly respected American Basketball League (ABL) several times, but the Rens were repeatedly refused. Only in 1948, more than 20 years after Douglas’s first attempt to join the league, were the Rens welcomed into the league. When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, Douglas made adjustments that were necessary to keep his team afloat during hard times. Most notably, he sent the Rens out on the road for months at a time and to areas such as the South where they had never played before. On the road, the team was the target of much greater racism than it had ever experienced at home.

The bias of many officials and bigoted spectators were just a part of the working circumstances that the Rens had to accept, and there was always the possibility of a riot. The Rens often slept at boarding houses, Black colleges, or even local jails, because segregated hotels and restaurants were off-limits to them. John Wooden, one the greatest coaches in collegiate basketball history and one of the finest players in the early era of professional basketball, played against the Rens during that period and said of them: “They were the finest exponents of team play I have ever seen…to this day I have never seen a team play better team basketball.” By 1937 the Rens were firmly established as one of the best basketball teams (Black or White) in the United States.

In 1939 that team was finally given an opportunity to do what Douglas had been yearning for since he first established the Rens. His team would play in the inaugural World Professional Basketball Tournament, sponsored by the Chicago Herald-American, in which the best professional teams chosen (without racial restrictions) would compete. The Rens beat the Harlem Globetrotters, the only other Black team in the tournament, 27–23 in the third round. They would go on to face the reigning champions of the White only National Basketball League (NBL), the Oshkosh All-Stars, in the finals. The Rens won the game handily, 34–25, and became the very first champions of professional basketball.