Black Soldiers Men and Women

Black Soldiers (Men and Women) have played key roles in the history (and success) of the U.S. military.

Black Soldiers have fought bravely in every major military action since colonial times. They bravely risked their lives for this country while often being treated poorly by racists both in and out of the military. Separated but never equal in war, Black soldiers were often ordered to perform dangerous missions, while at other times being relegated to menial labor duties such as building roads, cooking, or burying the dead. Black Americans were effectively barred from serving in any military branch besides the army until World War II. After each war ended Black Americans continually had their military contributions minimized, yet they often clung to the belief that military service in wartime could lead to greater freedom and opportunity for all Black Americans.

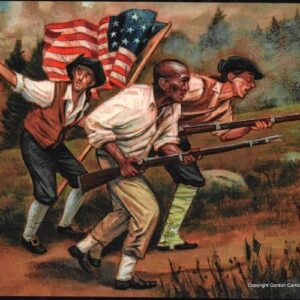

The Revolutionary War set precedents for Black military service. Both Africans and Black Americans fought on both sides of this war. After the war ended, slaves that fought for the British were either returned to their master or evacuated to Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone. Black soldiers from the north who had fought bravely in such battles as Bunker Hill helped convince leaders in several states to abolish slavery in later years. Many of the Founding Fathers, such as George Washington and James Madison, enslaved men, women, and children.

They pursued their own freedom while denying the rights and liberties to persons of African descent both enslaved and free. Black American colonists, free and enslaved, believed in the cause of liberty with its hopes and promises for a better future. Initially, over 5000 free and enslaved Black colonials fought with the Continental Army, even when such freedoms and liberties were not promised to them.

In contrast, around 20,000 free and enslaved Black colonials found the British promise of freedom to be more convincing, and fought as loyalist soldiers under the royal banner. In the view of enslaved and free Black colonials, the Revolutionary War became a test of what it meant to be free, and their experiences explored what it meant to be American.

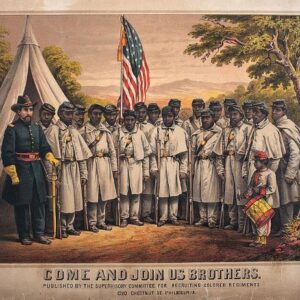

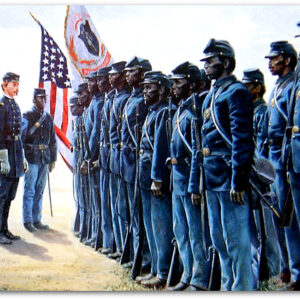

Upon the outbreak of the Civil War at Fort Sumter, South Carolina many freed Black men answered the call of the nation. Unfortunately, they were turned away, however, because a Federal law dating from 1792 barred Negroes from bearing arms for the U.S. army (although they had served in the American Revolution and in the War of 1812). In Boston disappointed would-be volunteers met and passed a resolution requesting that the Government modify its laws to permit their enlistment. It wasn’t until July 17, 1862, when Congress passed the Second Confiscation and Militia Act, freeing slaves who had their master’s approval.

During the war, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed remaining slaves from the confederate south. Although Black soldiers fought on both sides of the Civil War, the true victory was the abolition of slavery. The 54th Regiment Massachusetts Infantry was a volunteer Union regiment organized in the Civil War. Its members became known for their bravery and fierce fighting against Confederate forces. It was the second all-Black Union regiment to fight in the war, after the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

When the Civil War finally came to an end, 16 Black soldiers had been awarded the Medal of Honor. By the end of the Civil War, roughly 179,000 black men (10% of the Union Army) served as soldiers in the U.S. Army and another 19,000 served in the Navy. Black soldiers served in artillery and infantry and performed all noncombat support functions that sustain an army, as well.

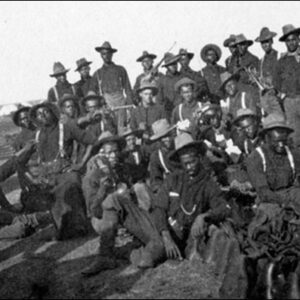

Following the Civil War, the Army disbanded the volunteer “colored” regiments, and established six Regular Army regiments of Black troops with White officers. In 1869, the infantry regiments were reorganized into the 24th and 25th Infantry. The two cavalry regiments, the 9th and 10th, were retained. They were known as the Buffalo Soldiers. These regiments were posted in the West and Southwest where they were heavily engaged in the Indian War. During the Spanish-American War, all four regiments saw service.

By the time World War I began, there were four all-Black regiments in the U.S. military: the 24th and 25th Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalry. All four regiments comprised of celebrated soldiers who fought in the Spanish-American War and American-Indian Wars, and served in the American territories. But they were not deployed for overseas combat in World War I. The first Black troops sent overseas served in segregated labor battalions, restricted to menial roles in the Army and Navy, and shutout of the Marines, entirely.

Their duties mostly included unloading ships, transporting materials from train depots, bases and ports, digging trenches, cooking and maintenance, removing barbed wire and inoperable equipment, and burying soldiers. Within one week of Wilson’s declaration of war, the War Department had to stop accepting Black volunteers because the quotas for Black Americans were filled. Facing criticism from the Black community and civil rights organizations for its quotas and treatment of African American soldiers in the war effort, the military formed two Black combat units in 1917, the 92nd and 93rd Divisions.

The French armies were facing a shortage, so they asked America for reinforcements, and General John Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, sent regiments in the 93 Division overseas to France. The 93 Division’s, 369 regiment, nicknamed the Harlem Hell Fighters, fought so gallantly, with a total of 191 days on the front lines, longer than any American Expeditionary Forces regiment, that France awarded them the Croix de Guerre, their highest honor for their heroism. The Harlem Hell Fighters got NOTHING from America! More than 350,000 Black American soldiers would serve in World War I in various capacities.

Black Americans made up over one million of the more than 16 million U.S. men and women to serve in World War II. Some of these men served in infantry, artillery, and tank units. As General George S. Patton Jr. swept across France into Germany, in his Third Army were Black Americans combat units. In 1945, there were approximately 240 field artillery battalions in Europe. Approximately eight of these battalions were composed of Black Americans. The 999th Field Artillery was one of these Black Americans battalions in Patton’s Third Army.

The 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion was unique at Normandy for two reasons. First, it was the only American barrage balloon unit in France and second, it was the first Black unit in the segregated American Army to come ashore on D-Day. The Tuskegee Airmen were the first Black Americans military aviators in the United States armed forces. During World War II, Black Americans in many U.S. states still were subject to racist, so-called Jim Crow laws. The American military was racially segregated, as was much of the federal government.

The Tuskegee Airmen were subject to racial discrimination, both within and outside the army. Despite these adversities, they trained and flew with distinction. Although the 477th Bombardment Group “worked up” on North American B-25 Mitchell bombers, they never served in combat. The Tuskegee 332nd Fighter Group was the only operational unit, first sent overseas as part of Operation Torch, then in action in Sicily and Italy, before being deployed as bomber escorts in Europe where they were particularly successful in their missions.

The 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion, nicknamed the “Six Triple Eight”, was an all-black battalion of the Women’s Army Corps. While more than 6,500 African American women served the U.S., the women in the 6888th recognized that their role as the only Black battalion serving overseas was unique and they were committed to succeeding and defeating the barrage of mail in the warehouses of Birmingham, England.

The Vietnam War saw the highest proportion of Blacks ever to serve in an American war. During the height of the U.S. involvement, 1965-69, Blacks, who formed 11 percent of the American population, made up 12.6 percent of the soldiers in Vietnam. Blacks faced a much greater chance of being on the front-line, and consequently a much higher casualty rate. Of all enlisted men who died in Vietnam, Blacks made up 14.1% of the total. This came at a time when they made up only 11.0% of the young male population nationwide. Of the 7,262 Blacks who died, 6,955 or 96% were Army and Marine enlisted men.

Early in the war, when Blacks made up about 11.0% of our Vietnam force, Black casualties soared to over 20% of the total (1965, 1966). Black leaders protested and Pres Johnson ordered that Black participation should be cut back in the combat units. As a result, the Black casualty rate was cut to 11.5% by 1969. Black Americans were more likely to be drafted than White Americans. The Vietnam War saw the highest proportion of Black soldiers in the US military up to that point.

Though comprising 11% of the US population in 1967, African Americans were 16.3% of all draftees. During the period of the Vietnam War, well over half of African American draft registrants were found ineligible for military service, compared with only 35-50% of white registrants. Black people were starkly under-represented on draft boards in this era, with none on the draft boards of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, or Arkansas. In Louisiana, Jack Helms, a Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, served on the draft board from 1957 until 1966. In 1966, 1.3% of the US draft board members were Black with only Delaware having a proportionate number of African American board members to the African American population.

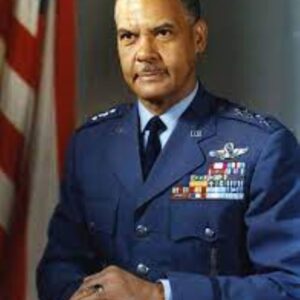

Across all branches of the military, African Americans composed 11% of all troops. However, a disproportionately small number were made officers, with only 5% of Army officers African American, and 2% across all branches. In 1968, out of the 400,000 officers, there were only 8,325 African American officers. Out of the 1342 admirals and generals, there were only 2 African Americans generals – Lieutenant General Benjamin O. Davis and Brigadier General Frederic E. Davison – and no African-American admirals. Racism against African Americans was particularly pronounced in the Navy. Only 5% of sailors were Black in 1971, with less than 1% of Navy officers African American. From 1966 to 1967, the reenlistment rate for African Americans was 50%, twice what it was for White soldiers.

During the bitter national debate on Vietnam, all public leaders within Black America were forced to choose sides. Black progressives in electoral politics began to speak out in opposition to the war. As a dedicated pacifist, Martin Luther King took a strong public stand against it. At the annual SCLC executive board meeting on April 1-2, 1965, King expressed the need to criticize the Johnson Administration’s policies in Southeast Asia.

Much to the dismay of colleagues who believed his antiwar sentiment would jeopardize the organization’s funding. In January 1966, King published a strong attack on the Vietnam War. In it he stated that Black leaders could not become blind to the rest of the world’s issues while engaged solely in problems of domestic race relations. While the initial response to King’s statement was negative, by the spring of 1966 the SCLC’ s executive board had come out officially against the war.

King understood that the massive military spending on the war in Vietnam meant that the nation had far fewer resources available to attack domestic poverty, illiteracy, and unemployment. King concluded that the Vietnam conflict had to end immediately. On April 4, 1967, speaking at Harlem’s Riverside Church, King announced: “It would be very inconsistent for me to teach and preach nonviolence in this situation and then applaud violence when thousands of thousands of people, both adults and children, are being maimed and mutilated and many killed in this way.” Eleven days later, Dr. King organized a rally of 125,000 in protest against the war.

Volunteers and draftees included many frustrated Blacks whose impatience with the war and the delays in racial progress in America led to race riots on a number of ships and military bases. Overt racism was typical in American bases in Vietnam. Although initially uncommon at the start of the war, after the Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., overt racism occurred at a higher rate.

Following the assassination, some White troops at Cam Ranh Base wore Ku Klux Klan robes and paraded around the base. At least three instances of cross burning were confirmed to have happened. In addition to being used in response to King’s murder, Confederate flags and icons were commonly painted on jeeps, tanks, and helicopters. Bathroom graffiti proclaimed that African Americans, not the Vietnamese, were the real enemy. Black troops were discouraged from taking pride in Black identity, with one troop ordered to remove a “Black is Beautiful” poster from his locker. Black identity publications and speeches were restricted, with some commanders banning recordings of speeches by Malcolm X or the newspaper The Black Panther.

African American culture and norms were also not initially acknowledged on bases. Black troops did not have access to Black haircare products, soul music tapes, nor books or magazines about Black culture and history. Instead, the Armed Forces Radio Network mostly played country music. Military barbers frequently had no experience cutting Black hair, and received no formal training on how to do so. By 1973, military barbers had been trained on how to cut Black hair.

The Armed Forces took some action to make Black troops feel more included. These included adding more diverse music to club jukeboxes, hiring Black bands and dancers for events, and bringing over Black entertainers to perform, such as James Brown. In 1970, 17 and 72 Miss Black America toured, and Miss Black Utah paid a visit. Base exchanges began to stock Black haircare products and garments like dashikis, while books about Black culture and history were added to base libraries. Mandated race relations training was introduced and soldiers were encouraged to be more accepting.

Ultimately, many of these changes were made towards the end of the war when personnel had been greatly reduced, meaning that a majority of Black troops who served during the Vietnam War did not benefit from these reforms. Black identity movements within Vietnam War troops grew over time, with Black troops drafted from 1967 – 1970 calling themselves “Bloods”. Bloods distinguished themselves by wearing black gloves and amulets, as well as bracelets made out of boot laces.

African American troops were punished more harshly and more frequently than White troops. A Defense Department study released in 1972 found that Black troops received 34.3% of court-martials, 25.5% of nonjudicial punishments, and comprised 58% of prisoners at Long Bình Jail, a military prison. It further remarked, “No command or installation…is entirely free from the effects of systematic discrimination against minority servicemen.” Black troops were also almost twice as likely as White troops to receive a punitive discharge. In 1972, African-Americans received more than one-fifth of the bad-conduct discharges and nearly one-third of the dishonorable discharges.

Throughout the overt racism, unrest and the distrust Blacks had of the military, there were twenty African-Americans Received the Congressional Medal of Honor for Their Service in Vietnam.

● James Anderson, Jr. ● Webster Anderson ● Eugene Ashley, Jr. ● Oscar P. Austin ● William Maud Bryant

● Rodney Maxwell Davis ● Robert H. Jenkins, Jr. ● Lawrence Joel ● Dwight H. Johnson ● Ralph H. Johnson

● Garfield M. Langhorn ● Matthew Leonard ● Donald Russell Long ● Milton L. Olive, III ● Riley L. Pitts

● Charles Calvin Rogers ● Ruppert L. Sargeant ● Clarence Eugene Sasser ● Clifford Chester Sims ● John E. Warren, Jr.